ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

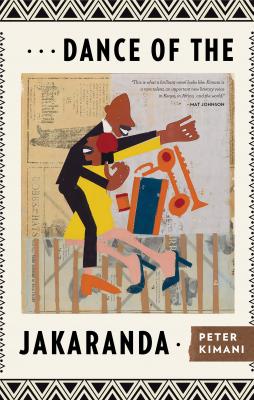

Dance of the Jakaranda. Peter Kimani

Читать онлайн.Название Dance of the Jakaranda

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781617755033

Автор произведения Peter Kimani

Жанр Книги о Путешествиях

Издательство Ingram

The cup by the balcony was for four o’clock tea, taken with biscuits or fruit. This trail of teacups wouldn’t be collected by their servant until Sally went out for her evening walk because she did not like her solitude to be interrupted. Solitude was the reason she gave for postponing motherhood.

“I can’t handle children,” she said earnestly. “Running noses and wet bums I can, but not the cries from toothless gums.”

McDonald had long taken note of the trail of cups but voiced no concern. Like the wise soldier he considered himself to be, he had learned to pick his battles wisely. So on that fateful morning, afraid to disturb Sally’s peace, he sneaked quietly into the house to collect his diary. He was tiptoeing out when he heard a moan from the bedroom. He paused and cocked his head. He heard another moan. It sounded like pleasure, and he doubted that Sally could have derived that from the big-eared thoroughbreds in her magazines. He made his way to the bedroom door, silently opened it, and entered. Sally’s face was not burrowed in some magazine as he suspected; actually, he couldn’t even see her face—the view was blocked by the back of a head he found eerily familiar.

He could see that it was a man’s neck, sinewy from his present labors and engaged enough in his task at hand not to sense McDonald’s presence. McDonald realized it was his black gardener; he had seen the man strike a similar pose as he worked—fondling soil to pick out a weed or pruning the bushes. Now he devoted similar attention to this chore, and for a while, neither the man nor Sally noticed McDonald. When Sally finally did, and screamed, the black man thought she was screaming because of something he had done, so he continued on. It was only when McDonald dropped his diary, his trembling hands unable to hold anything, that the man realized the intrusion. Where does a man hit another to inflict the most pain, without injuring one’s ego that the invader’s very presence under his roof seeks to quash? McDonald appeared hypnotized by the puzzle, much the same way vermin are dazzled by the sudden burst of light when emerging from a crack in the furniture. McDonald’s soldierly instinct was to cut off the offending organ, but he had no idea what he’d do with it. A soldier had to envision a whole operation before setting forth. Should he throw it to the dogs? Keep it as a memento? He didn’t even have a weapon in hand. Perhaps he could use his teeth, but that would intimate a certain rage. He wasn’t a savage. Yet.

He obviously did not approve of the man’s presence in his bed, but his training taught him to keep emotions out of his work. That’s why guns had been invented—to create distance between assailants and their victims. He tried to catch a leg, but the man was as slippery as a fish. He noted how feminine the man’s shin felt, bereft of hair or scars. McDonald was determined to leave a lasting mark.

He dashed out of the bedroom to retrieve a weapon from his bag in the sitting room, but quickly remembered it was in his rickshaw waiting outside. He was losing crucial time, so he sprinted back to the bedroom, only to find that the man had disappeared out the window. Sally had gathered herself and was sitting on the edge of the bed, downcast.

For several long moments, he glared at her, trembling with anger as well as the fear of what he was contemplating. He slapped Sally once, and being a soldierly slap, it left a buzzing sound in her ear.

When he was confounded, as he was then, words utterly failed him. And when he finally spoke, it was neither a personal rebuke nor a remonstration. “Even if you have to do these things, don’t you want to be respectful of the law?” McDonald glared, before walking away. It was a useful reminder that under the apartheid laws in South Africa, miscegenation was outlawed, so Indians, blacks, whites, and coloreds were prohibited from mating outside their own races. While the statement conveyed McDonald’s allegiance to the law, it was also his way of saying: You can do what you want to do, but surely not with blacks.

The incident was not discussed any further; they were giving each other what Nakuru folks liked to call “nil by mouth.” Neither uttered a word to the other, McDonald humiliated into silence because there was no way he could broach the topic without raising doubts about his abilities as a man. After all, his wife had not been caught stealing food or clothing; she had steered her servant, her black servant, away from the flower beds to her own bed, to perform a role that McDonald had either failed to do or had not performed to her satisfaction. Sally, on her part, remained silent because she had lost hearing in one ear and was too upset to talk anyway.

So McDonald had seen his posting in the new colony of British East Africa as an escape from personal turmoil and humiliation. Perhaps he and Sally would even have another shot at their troubled marriage.

I shall be the lieutenant of the entire province, he had written to her. With a dozen servants at my disposal so even when I cough, one is likely to check if I had called for him . . .

Sally’s response had been terse: Even if you were the governor, I’m not going anywhere with you, now or in the future.

Sally, whose rich background and royal roots had been a permanent source of ridicule from McDonald’s peers, said she would remain in England for the rest of her life. He then prevailed upon her not to file for divorce—to give them a bit of time to review things.

McDonald then resolved to do what he knew best: work hard and earn a decoration for his service to Great Britain. Sally would be proud of him, he mused to himself, perhaps she’d even harken his word. If he was knighted, he would be a man of title, just like her father. That’s what motivated him to go to East Africa—to head the project that even his bosses in London admitted was a little insane. Its London architects called it the Lunatic Express, wondering where the rail would start and where it would end, for nothing of value was to be found in the African wilds. But it had to be done, and McDonald had fully committed himself to the idea that the construction of a railroad across the African hinterland was his route to self-affirmation and validation. But soon after he arrived in the marshes that grew into Nakuru town, few locals believed he was anything but completely nuts.

* * *

Ian Edward McDonald’s Years of Solitude—as his four-year seclusion came to be known in Nakuru lore—far surpassed the few hours that Reverend Turnbull was reportedly in the belly of the iron beast, and, if one were to allow his mythical parallel, the three days Jonah spent in the belly of the whale. And even the forty days and nights that Jesus spent in the wilderness. But where myth and history often intersect, and the past often collides with the present, it is imperative to clarify the circumstances surrounding McDonald’s house and Sally, the woman for whom it was built. For one cannot talk about the Indian singer Rajan, the love slave, without talking about the original ngombo ya wendo, since the two narratives both start and end at the place: the house that McDonald built—set between a hot spring and a cool lake—which ultimately became a site of unseemly arguments and simmering loves. To absorb the full story, one must turn back the hands of time and think about the dry savanna where only stunted acacia stands, their spiky hands thrown up in surrender against the harsh sun. That was McDonald’s inheritance of loss, the bittersweet consolation for the coveted peerage from the Queen of England that had fallen through the bureaucratic cracks between London and its colonial outpost of Mombasa.

So, as was typical of McDonald, he ignored any signs to the contrary and continued dreaming that another future was possible for him and Sally. He saw the virgin territory and trembled with lust. He would conquer nature and assert his control, make something out of it for himself and, in the process, leave his mark on the world. He had been to different territories in the colony where locals had adopted names of missionaries who had ventured there, and remembering them, he felt a clog in his throat, for long after those men of God were gone, memories of their life would linger. There was Kabarnet, named for Reverend Barnett who had pitched a tent in Nandiland. Or one could point at Kirigiti in Kikuyuland, where the Brits’ love for cricket had earned them immortality in the name of the place.

Above