ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

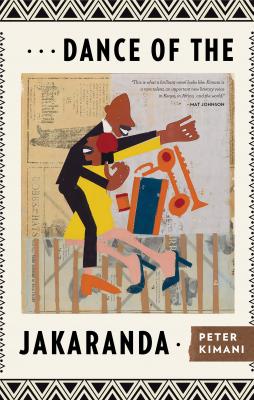

Dance of the Jakaranda. Peter Kimani

Читать онлайн.Название Dance of the Jakaranda

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781617755033

Автор произведения Peter Kimani

Жанр Книги о Путешествиях

Издательство Ingram

The watering hole, so named due to its proximity to the wild animals’ drinking point, became a favorite spot for tourists, as well as locals across the racial divide. But since all the races had never before interacted socially, their initial meeting resembled nervous animals coming in contact for the first time; if animals started by nosing their opponents’ horns, humans began by sizing each other up from a distance, commenting on news events, then finally warming up and sitting at the same table to share a drink.

Rajan scanned the female faces and settled on several sets of lips turned in his direction. They were mostly Indian and African lips, thickened with layers of Bint el Sudan and Vaseline. There were no white women present. Rajan’s hopes were waning. He licked his lips again, shaking his head to fend off the gnawing thought: why would a single touch from a woman cast such a strong spell on him? The mysterious taste seemed to be dissipating now, which only heightened his despair.

He stepped out and walked aimlessly, before taking the path leading to the butchery, hoping the kissing stranger had somehow ended up there. The butchery was the spot where his grandfather Babu sat during his maiden trip to the establishment, a visit that was made after weeks of coaxing. Babu had simply said, without any elaboration, that it didn’t feel right for him to venture into the Jakaranda for ancient historical reasons. When Rajan persisted in his demands for an explanation, Babu said: “A foolish child suckles the breast of its dead mother because he can’t differentiate between sleep and death.”

Rajan often wondered if the ancient history Babu had in mind related to McDonald, the elderly owner of the ranch that became the Jakaranda, and who still lived in a house on the sprawling property. McDonald occasionally dropped by to watch Rajan and his band rehearse. On such occasions, the old man would stand, nodding his head to the beat, before retreating as silently as he had arrived, the shuffle of his feet interspersed with the gentle knock of his walking stick. Rajan noticed McDonald had started paying more attention to him since learning Babu was his grandfather. “Greet the old cow for me,” McDonald would say to Rajan as he trod away.

Rajan never conveyed the message because Babu grew tense every time he mentioned McDonald or the Jakaranda, though he still managed to convince his grandfather to shake off that ancient history and show up there to watch him perform.

The butchery was located in a building that had once served as the servants’ quarters of McDonald’s house. One wall had been removed to provide a view of the animal carcasses that hung upside down. This area offered a panoramic vista of the plains as well. The electric fence still stood between the establishment and the wilds. The animals still came to the watering hole but the mating had died down. Tourists’ cameras had replaced guns on the shooting range. Most people suspected the animals found the flashing cameras intrusive, or perhaps the animals could tell camera flashes did not threaten their survival like the booming guns, and so did not feel the pressure to procreate. But few thought the animals could have been corrupted by the humans, whom they had watched doing their thing for many years. The animals had acquired the human habit of experiencing thrill only when under immense pressure.

Rajan considered the contrasting appearances of the cooking meat, the raw meat, and the animals roaming the wilds. One was at liberty to choose the animal he wanted killed for dinner. The majority of the meat was from goats, sheep—lamb and mutton—chicken, and turkey, all having replaced the dairy cows. The meat was grilled, broiled, fried, roasted, or made by the tumbukiza method, which involved throwing the meat, vegetables, and spices into one big soup pot to cook together. A charcoal brazier, the size of a man, sat outside the butchery—its wobbly, spindly legs holding amazing amounts of meat, the multiple apertures breathing laboriously, as if bogged down by the demand of giving fresh life to coal from dead acacia stems and shrubs and fossilized bones. Eventually, after spasms of seething, sighing, and hard breathing, the brazier would spark gently to life, turning the layers of black coal to dawn brown, before glowing evening red. The brazier was the glue that held white, pink, black, and brown hands together, pointing at the pieces of meat they claimed as their own.

It was a site of unbridled desire as men and women salivated over the cooking meat, while others watched the animals and developed their own appetites. All were there to eat their fill, and the task of feeding them fell on Gathenji the butcher, with his reassuring leitmotif, “Ngoja kidogo!” which meant one needed resolute patience when dealing with him, for his “wait a minute” often lasted a few hours, usually because Gathenji sold meat faster than he could roast it, and some hungry patrons were more than willing to induce his cooperation with a little extra money.

Rajan surveyed the butchery, reminded once again of his grandfather. When Babu had visited for the first time, he observed even with the promise of independence that men were still hunters and gatherers; women waited at the table to be fed. True to Babu’s word, there was not one woman at the butchery.

Babu and Gathenji had instantly hit it off. It was one of those quiet nights when the month was in a bad corner, which meant somewhere around the third week, when people had exhausted their midmonth advances and the next paycheck felt years away. Babu, slouched and supporting his frame on a walking stick, had barely settled in his seat when Gathenji marched over to the table and bowed in unctuous deference. “This is the man himself!” the butcher had saluted Babu, placing a wooden tray bearing a piece of meat on the table. “This is kionjo, just a small bite to silence the pangs of hunger,” he said generously, slicing the tangled meat open, the juicy parts yielding drops of oil as he proceeded to cut it into tiny pieces. “You know, we have heard so much about you, mzee . . .”

“I hope you have heard the right things,” Babu had replied, glowing as he turned to his grandson Rajan. “He keeps asking me to tell him stories from the past. But I don’t know how he retells them.”

“He does it very well,” Gathenji assured, then went on: “You know, now that we are about to celebrate our independence, you stand tall as one of our fathers of the nation.”

“Not so loud,” Babu cautioned. “Some don’t think of fatherhood as a shared responsibility.”

“Never mind, you are our father. Tell me, where did you learn all those languages? Swahili, Kikuyu, Dholuo, Kalenjin?” Gathenji pressed.

“Well, it was all in a day’s work,” Babu allowed. “I worked with men from different communities, so I learned their languages.”

“And you know the most difficult part of it, my good mzee?” Gathenji said. “You built the rail with those hands of yours . . . the rail that now links the land of Waswahili to that of Wajaluo, Wakikuyu to Wakalenjin.”

“It was all in a day’s job.”

Gathenji waved him down. “Hold it right there, ngoja kidogo.” He had noticed Babu was not eating and still had his false teeth in. Gathenji dashed to the butchery and returned shortly with a mug of muteta soup and a glass of water into which Babu dropped his dentures, sipping the soup as he did so. They managed this exchange without a word.

“I hear this very house has an interesting tale to tell,” Gathenji said conspiratorially.

“Careful,” Babu smiled, flashing his bare gums, “walls have ears.”

“I agree,” Gathenji said. “Let’s not gossip about the stream while sitting on its rocks.”

“Words of wisdom.”

Gathenji was summoned back to the butchery by a customer. Babu took another sip of the soup and sighed. It was spicy, just as he liked it. He took a bite of mutura and chewed nervously, wondering if the meat was halal. Although he wasn’t very religious, he liked to eat right. The mutura was delicious, if a little oversalted.

Soon, Rajan took to the stage, calling the audience’s attention to the special guest in the house. Babu waved his walking stick from his seat as the revelers ululated.

*