ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

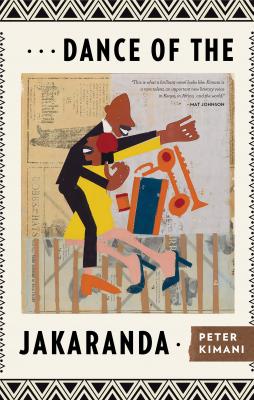

Dance of the Jakaranda. Peter Kimani

Читать онлайн.Название Dance of the Jakaranda

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781617755033

Автор произведения Peter Kimani

Жанр Книги о Путешествиях

Издательство Ingram

Rajan had propped himself on his right elbow and looked intently at the girl. Even in the faint light, he could tell she was strikingly beautiful. Her naked breasts, like filled jugs, stood erect, the wide hips seemingly out of sync with her slight frame. Her calm and beautiful presence appeared misplaced amid the riotous din from the butchery, the chorus of drunks ordering fresh rounds, the whimper of music equipment under the weight of two adults.

Rajan had kept quiet.

“Soooo, did you hear my question?” Angie had repeated without any hint of annoyance. Rajan could feel his indignation rising, like heartburn after a good meal. What did the girl expect him to say? And why did she impose her expectation that she should mean anything to him?

Angie had gotten dressed and stood to leave. “If you want to see me, I will be at Moonshine tomorrow at four p.m.,” she announced. “They serve nicely brewed tea.” Moonshine was another previously whites-only establishment, and young African women were quickly catching up with white culture, like having four o’clock tea. If this was the new African woman, Rajan shuddered, he and his ilk were in trouble. The era of free things was about to end.

Rajan had grudgingly honored the appointment the following day but arrived half an hour late.

“There is no hurry in Africa!” Angie said cheerfully. “You must know you are worth waiting for.” She was sitting by the pool, next to a whitewashed wall. An inverted image of Angie was submerged in the water, an image that threw Rajan’s mind to his grandfather Babu’s story of his treacherous journey by boat from India to Mombasa many years before.

Rajan had approached the girl. She looked remarkably different from his night visions. He remembered her spiky hair falling all over her face. Now it was pushed back and pinned, accentuating her forehead that shone against the sun. The high cheekbones were still sharp, perhaps sharper than an artist’s chisel, and her calm face, almost childlike, contradicted the mature, worldly mask Rajan had seen at night.

Accustomed to the dark and the comfort afforded by multicolored lights, Rajan had blinked like an animal out of his lair. He realized for the first time how rare it was for him to face the daylight. He typically slept through the day and sang at night. He found the sun blinding. He did not know what to say, for he never had to say anything to women. They all arrived at his feet seduced by his music, and hurled their bodies at him without a word. The best effort he ever made was to stretch out a hand and pick his chosen few from the sea of besotted fans. His microphone was the magic wand that drew them to him; without it, he was powerless.

Angie held his hand and squeezed it, her eyes dark with power and mystery. He cringed and thought of the image in the pool, envisioning their gazes mirrored in the water. He felt like he was drowning in the pool of her eyes and his hand went limp in hers. Unable to keep his grip, he lowered his gaze and pulled his hand away, then excused himself to go to the bathroom, although he felt no urgency at all. He used the back door and made his exit. He had not uttered a single word.

Quite often, Rajan woke up in beds where he could hardly recall how he’d gotten there in the first place, but where he did not need to utter a single word to get things going. Quite a few times, it was with a hint of regret, dodging kisses from stale mouths or breaking free before his captors could grant his leave, extricating himself from a mess he did not wish to get tangled in. In such circumstances, older women were usually the culprit. He dreaded their insistence on small talk that could only end in hurt—he was there to have a good time, not chat about life. Worse still, some sought his thoughts on their immediate future under a black ruler. But the one thing that he enjoyed was bedding different generations of women and assessing their values and attitudes toward life and love. He had discovered that all women, whether young or old, sought an affirmation of love—or at least some declaration that they meant something to him. The truth was, they did not, and he suspected that they knew as much, yet couldn’t quite leave him alone.

Then the kissing stranger arrived and disrupted everything. Just like that. For the lavender-flavored kiss on that balmy June night in 1963 breathed into Rajan a restlessness that infected his mind, and later his heart.

There were the awkward moments when he’d stop in his tracks, convinced a girl he passed on the street was the kissing stranger, only for her physique to transform into an image different from the one in his mind. At other times, he would walk into the washrooms at the Jakaranda to retrace her steps; he made so many trips there that his band members started speculating that he was suffering from a serious case of diarrhea.

In moments of despair, he stood on street corners scanning the women passing by before marshaling up the courage to confront one with a ready line, only to falter upon closer scrutiny. He thought the kissing stranger had dimpled cheeks, with a gentle smile playing on her full lips as she seductively swished away. But in other visions she would appear chubby and unsmiling. Occasionally, he found he had assigned her features from different women from his past until he got all mixed up. Then he would remember he’d never actually seen her face because it had been so dark.

One morning, Rajan went from door to door inquiring about young women who wore high heels. He pretended he was a fashion photographer looking for models to parody the flamingo dance, which was all the rage at the time. But no one ever remembered seeing anyone in high heels, the question only serving to remind many that they did not wear any shoes at all. The irrationality of his inquiry was amplified by a middle-aged woman who remarked: “Could anyone go tilling the land or carrying a load of firewood on her head in the kind of shoes you are describing?” The woman clasped her cracked hands to display her dismay and squeaked, “Yu kiini!”

He did not gain access to any white homes because no one answered the doorbell and he was afraid of venturing in unannounced, since most homes had signs warning of mbwa kali, or ferocious dogs. The search bearing no fruit, Rajan broached the idea of placing an advertisement in the Lonely Hearts column of the Nakuru Times. But who was he looking for? Was she tall or short, slight or heavy? How many Nakuru women would fit that bill? Was she white, black, or brown? He froze at that question. Who among the three groups could have kissed with such sophistication? Probably a white girl, but then Africans, Indians, and Arabs were racing to make up for lost time, and could probably give whites a run for their money after only a couple of months of freedom.

Had he known the ethnicity of the kissing stranger, would that have narrowed his search and yielded better results? He reckoned that would actually be problematic, for how could he describe the subject of his admiration without arousing his prejudices about her imagined history? After all, humans do not wear identities on their faces. Where would he place her in a land where dozens of communities existed? And how could he describe himself anyway? A Kenyan of Indian ancestry seeks a lean, pretty woman who can wear high heels in the dark . . . ?

And would it be accurate to describe himself as Indian when his only encounter with the subcontinent was through the stories he had heard from his grandparents? He realized to his horror the perils of history and the presumptions that come with symbols. A turban may be the mark of a Sikh, but the Akorino of Molo and Elburgon wore them too. In that place, anybody could be anything. And when things appeared set and certain, nature erupted to remind him of the temporal nature of man. A dormant volcano leaped to color the land ashen gray. A landslide tossed a mass of red earth to bury houses in the bowels of the earth, erasing the markers that people had used to define their existence.

Eventually exhausted by his fruitless search, Rajan returned to his routine at the Jakaranda of drinking and eating and performing.

The Jakaranda wasn’t just home to Rajan’s personal melodrama; the atmosphere of the hotel was also spiced up by the butcher Gathenji’s own spectacle—his tools of trade a sharp cleaver, acerbic wit, and swift feet, which were unfailingly thrust in ill-fitting flip-flops, the big toes nosing the ground for any trouble. Picture the man