ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

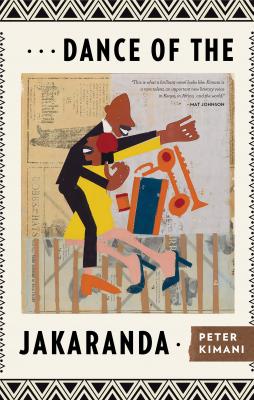

Dance of the Jakaranda. Peter Kimani

Читать онлайн.Название Dance of the Jakaranda

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781617755033

Автор произведения Peter Kimani

Жанр Книги о Путешествиях

Издательство Ingram

So, soon after his discharge was confirmed, and London reaffirmed that the coveted title for his service to the empire had been erroneously replaced with a deed to a piece of earth he neither desired nor needed, McDonald wrote to Sally. His first letter went unanswered. And the second, and the third, and the fourth. She answered his seventh letter, clarifying that she had been prompted to respond not by his persistence, which she remarked was a sign of foolishness—a wise man has many ways of sending a message, she said—but because the last letter had arrived on her birthday. Any meanness of spirit wasn’t permissible on her special day.

Sally said she would think about the visit, which to him meant his request had been considered favorably. He knew Sally was not the thinking type; she acted on impulse, so any claim that she was thinking things through was, in fact, an affirmation that she had already made her decision. Her final letter with confirmation of dates and itinerary arrived six months later. She would be visiting in another six months. She then added:

I’m curious to how you use your fork and knife these days. I recall you had trouble drawing butter from the jar and putting it on the side plate. You liked buttering your bread direct from the jar, which ticked me off without fail. I suspect you must be eating butter directly from the jar since, in your military wisdom, bread and butter eventually meet in the stomach.

Sally wanted to find out if he had gone native, McDonald thought happily; he would prove to her he had only grown more sophisticated. He would demonstrate to her that he was as good as any Englishman; in fact, he was as good as her father, whose country home in Derbyshire he replicated in the design of the Nakuru house. He worked his men like donkeys, most of them artisans he had diverted from the team detailed to maintain the new railway, and so worked at no cost to him. None of them knew their old boss had been retired.

The concrete blocks were sourced from other faraway colonies like the Congo and Nyasaland and hauled uphill by African handymen. The blocks were used as cornerstones that were a slightly different shade from the rest of the wall, and were placed at calculated intervals to evoke the pattern of a staircase. Once again, McDonald maintained the division of labor he applied on the railway construction. African laborers teamed up with an Indian artisan. A white architect named Johnson—whom the African workers called Ma-Johnny—provided general oversight.

Workers sang songs to urge others; they cracked jokes to deflect attention from their backbreaking toil. “Hey, man, a bird is going to perch on your head thinking it’s a tree!” one worker would tease another who was considered lazy.

“Maybe he will help build its nest,” another would join in.

During the rail construction, McDonald had discouraged joking among the workers because he believed those busy using their tongues were misdirecting their energies. But he had become more tolerant during the construction of the house—not that the workers necessarily knew this. To be on the safe side, the workers continued to fall silent at his approach.

When workers fell short of their projected goals, McDonald organized overnight shifts. That’s when the glowworms in the marshes were replaced by lightbulbs and locals who had never experienced electricity were drawn to the lights, just like the moths that buzzed around the bulbs, singeing their wings and doing their death dance before paving the way for more suicidal insects. The locals stood and marveled: Muthungu ni hatari, they said, admiring the discoveries the white man had brought to their village. In that spirit, few spoke about the builders who had been killed or maimed in their labors, or devoured by wild animals at night while working. And those who did speak of these casualties concluded with philosophical zest: an abattoir is never without blood.

The house was completed in ten months, sixty days ahead of the projected deadline. McDonald devoted the last months to supervising the gardens as well as the jacaranda trees that he ordered planted along the road that led from the train station to his house so that Sally would be garlanded by purple blooms when she set foot upon the land in 1902. The idea of the blooms came straight from the Bible, or McDonald’s vague recollections from Reverend Turnbull’s sermons about Jesus’s dramatic entry into Jerusalem garlanded by palm fronds from enthused followers.

He thought the jacaranda reflected Sally’s beauty, and the trees were in full bloom when a horde of servants in a horse-drawn chariot was dispatched to fetch Sally from the Nakuru train station, only a few miles away. Some of the trees had shed their leaves, turning the black earth into a purple carpet. McDonald stayed home to receive guests who had been invited for the banquet. A band had been invited all the way from Nairobi to perform, as was the chef and the kitchen staff. It was the same chef who had cooked for the first colonial governor in 1901, and would be detailed to cook for the Queen of England when she visited the colony years later. The freshest English pastries had been delivered on the weekly flight that brought in the mail from Nairobi. The smells wafting, the piped music floating on the air, combined with the modulated laughter from guests who had already arrived, provided a sense of joy for those assembled.

At the dining hall, a matron hired from Nairobi had drawn up a list to ensure the right sort of people sat together. Engineers from the railway department, for instance, would sit with hoteliers and civil servants and businesspeople. The idea was to mix all manner of professions to spice up conversations and put different perspectives to debate.

The lilting music from the cellos and wind instruments was exactly right for the light refreshments being passed around. Reverend Turnbull was seated between an anthropologist named Jessie Purdey on field research from the University of London and a retired district commissioner named Henry James. On the other side of the table was a youngish woman with a sunburned face and freckled nose. Her name was Rosemary Turner and she giggled when Reverend Turnbull introduced himself.

“How can a reverend have such a cocky name?” she drawled. She proceeded to spend the rest of the evening stepping on his shoes and pinching his thigh.

What followed remains a topic of heated debate to this day, without a discernible conclusion or concurrence. With the passage of time, previous rumors would acquire more sinister pegs so that Sally, the malkia, became a legend in her own right. But as local people like to say, where there is smoke, there is fire, and the smoke and smog that clouded Sally’s visit had one consistent thread: she made a brief appearance at the party incognito before exiting fast.

There were claims that she sneaked into the party disguised as a beggar to test McDonald’s kindness, and was promptly chased away by the guards. Yet others claimed that when she arrived on the coast, she had visited a medicine man who gave her special herbs and charms that allowed her to transform herself into a cat, to spy on McDonald’s house and his friends before making her quiet exit, never to be seen again. Another rumor that became firmly entrenched in the Nakuru lore was that Sally arrived without any disguise, took one look at the edifice built in her honor, sneered that it resembled a chicken coop, and spat on the ground to show her disgust before walking away, with McDonald in tow, pleading with her to return to him.

So, to lay the debate to rest, here’s the true version of the events of that day: Sally arrived on the train from Mombasa as scheduled and saw the African servants waiting to receive her. They were holding a placard carrying her name. On it was McDonald’s looped scrawling, identifiable from a mile away. Sally waved at the servants, who scrambled for her luggage and packed it in the carriage. As she hoisted a leg up to board the carriage, that aforementioned cheeky whirlwind did its thing and she was left with her skirt briefly covering her face, mildly embarrassed but otherwise in good cheer, even after the servants abandoned their mission. The horse trotted back home without the distinguished guest but bearing her luggage.

McDonald panicked when he saw the horse return with the two suitcases but without the servants or Sally. He responded with mathematical precision: adding all the facts together, he concluded that the servants and Sally were together, as memories of that morning in South Africa flooded back to him. He paused to think further; there were four servants involved. Even with Sally’s preponderance for bedding her servants, she certainly couldn’t