ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

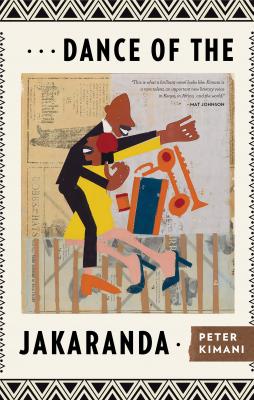

Dance of the Jakaranda. Peter Kimani

Читать онлайн.Название Dance of the Jakaranda

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781617755033

Автор произведения Peter Kimani

Жанр Книги о Путешествиях

Издательство Ingram

Malaika, nakupenda malaika

nami nifanyeje

kijana mwenzio . . .

The crowd roared appreciatively as the band started to play the slow love song they all knew by heart. Mariam flashed a coy smile and rose to her feet. The instantaneous clamor was enough to lift the roof off the Jakaranda, so that even Mariam could no longer resist the serenade. She made a few strides toward Rajan, who led the way toward the stage, doing a little dance because he could hardly contain his elation.

When she hesitated at the staircase leading to the dance floor, Rajan swept her off her feet, rocking her in his arms. She proved heavier than he had anticipated and Rajan staggered, nearly missing a step before regaining his balance. She swooned with pleasure, or perhaps fright, as he took the stairs before depositing her onstage. She steadied herself, her wide, circular silver earrings shining against the oscillating lights. Her mass of thick hair reached her waist. She smiled broadly, revealing twin dimples, straightening a crease on her long skirt as she did so.

If this was the kissing stranger he had encountered in the dark, Rajan thought, she certainly wasn’t afraid of the spotlight.

The love song faded and was replaced by a mugithi tune, bringing onto the stage the stories that Rajan had been told by his grandfather Babu about his experiences building the railway. The dance imitated the movement of the train and Rajan guided Mariam to join the trail of revelers doing their rounds through the dance floor, their feet spread wide apart to imitate the railway, every lap around the premises marking a completed journey.

The next tune was called the dance of the marebe. It involved thunderous drumming followed by the wail of the guitar and the blow of the sax. It was called the dance of the marebe because it told the true story of the Indian trader who encountered a lion in the Tsavo forest as he led his mule to the camp. The mule carried on its back pails of paraffin and when the lion struck, Babu had narrated to Rajan, its claws got stuck in the ropes holding the pails. The mule attempted to flee but was paralyzed by fear and the additional load on its back. The lion could not extricate himself from the hessian ropes. The pails of paraffin clanged together as the mule hee-hawed, trying to shake the beast burdening his back.

The song climaxed with even heavier drumming that represented the clanging pails, an act Chege the drummer delivered with great drama. He would glide from one drum to another, teasing revelers that the skin drums were not taut enough and needed heating. He would make as though to head toward the butchery, but fans would wave him away, hurling coins onto the drum that Chege accepted with comic deference. It someone offered a note, especially if the giver was a woman, he would direct them to deposit it into the waistband of his pants, his bare chest glistening with sweat.

* * *

Rajan was tongue-tied when he was finally alone with Mariam backstage at the end of the concert.

“Sorry for the late introduction,” Mariam said, finally introducing herself properly. When Rajan stated his name, she smiled sweetly. “Who doesn’t know you . . . ?” she breezed.

Rajan simply stared back, dazzled by the beauty that seemed to radiate out of her every pore. Her face glowed at her every turn, and her circular, silvery earrings danced, oscillating in the darkened space. She was in high heels, and Rajan realized to his horror that she was taller than he. She was so beautiful, he couldn’t imagine her doing any of the ordinary things ordinary folks did, like having a bowel movement. He couldn’t imagine such ugliness from her gorgeous form.

“You are suddenly very quiet,” Mariam whispered.

He wanted to shut his eyes and be serenaded by her cooing voice. His mind was racing through the past few months, when the mere thought of Mariam diminished his hunger pangs and set off such an acute desperation that he feared he was losing his mind. He remembered the many sleepless nights he had agonized about her, and now here she was, in a poorly lit space close to their original point of collision, looking even more lovely than he remembered her. The memory of the kiss resurged with such power that Rajan staggered toward Mariam and pulled her toward him.

“Hey, hey, pole pole,” she protested. “Don’t jump on me as though I’m a stolen bicycle.”

Rajan laughed. “You just can’t imagine how long I have waited for this moment . . .”

“I thought we barely met an hour ago,” Mariam replied.

Rajan stopped himself before blurting about their first kiss in the dark and how it had affected him. He needed to kiss the girl again to confirm she was the one.

“I want to go home,” Mariam said.

“You want me to take you home?”

“That’d be nice,” she smiled.

“Where do you live?”

“Where do you live?”

“You mean my home?”

“Where else do you call home?”

“I am home right now!”

“Stop pulling my leg.”

“I wish I could pull your leg!” Rajan smiled even as a knot of panic congealed in his stomach. Home meant the house of his grandparents, Babu and Fatima. This girl wasn’t possibly thinking he’d take her there on their first night out.

Rajan was suddenly awash with shame. At twenty-one, he still had not moved out, and possibly wouldn’t ever leave home because he was a Punjabi boy. He was bound to live with his grandparents his entire life. He envied his bandmates who all had their private spaces outside the family homes. Era had his small dwelling that was detached from his mother’s house. It wasn’t much, just a tin shack—ten by ten feet, meat paper on the walls, a single bed, and an earthen floor. But Era derived great prestige when he told the other band members: “I have to rush home, I got a bird in the cage . . .”

Rajan could never dream of saying such a thing. The backstage operations at the Jakaranda served to minimize such complications.

He had never taken any girl home to his grandparents, but then again, none had ever expressed such a desire. They seemed content to consummate their lusts backstage. But this was no ordinary girl; he had searched for her for nine months and she wanted to be handled pole pole. She was not a stolen bicycle.

* * *

That night, Rajan and Mariam ended up at Era’s tin shack on the fringes of Lake Nakuru near the kei apple trees and fence that separated Indian from African quarters. The white quarters towered above, close to where McDonald had built his house, the layout of the township forming an unstable triangle, each race on a far end of the lake.

It was at that hedge separating the Indian and African quarters that Era had first encountered Rajan fifteen years earlier. Era was nine; Rajan was six—his small head appearing one day just above the hedge that stood between his family’s house and Era’s.

Era’s principle memory of that first encounter was how Rajan resembled the portrait of Jesus that adorned their living room—only the crown of thorns was not standing on Rajan’s head, it hung around his neck where the hedge reached.

“Maze, umeona mpira?” Rajan’s had asked during that first encounter, his tender voice trilling like a flute.

“Eeeeeehhh?” Era shouted.

“Our cricket ball.”

“Where is it?”

“It just rolled under the fence,” the boy with the thorny garland said. “Have you seen it?”

Era pretended to be looking,