ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

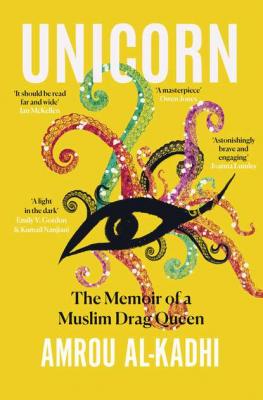

Unicorn. Amrou Al-Kadhi

Читать онлайн.Название Unicorn

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780008306083

Автор произведения Amrou Al-Kadhi

Жанр Религия: прочее

Издательство HarperCollins

She was mine for the rest of the night. Because my hand was so badly blistered from the ‘accident’, she stayed with me as I slept. I lay on the couch, with her on the floor next to me, holding up my hand so that I didn’t hurt it during my sleep. And she sat like this until I woke up the next morning – my beautiful, generous mother. Now I realise these were extreme measures to take for a moment of maternal comfort. But believe me when I tell you: there was no other option besides Mama.

Dubai was my home until the age of seven, Bahrain till I was eleven. Where I was raised, there was a marked distinction between the masculine and the feminine. I grew accustomed to binaries from a very early age, even though I had no awareness of the concept of them. The earliest recollection I have of a strict division between the sexes was when my mother drove to the border of Saudi Arabia (my brother and I were curious to see it). My mother edged to the border and drove away again. ‘But Mama, we want to go in,’ I implored, confused about what was stopping her. ‘Women aren’t allowed to drive in Saudi,’ my mother said with a remarkable calm, as if the patriarchy lived harmoniously inside her, at one with her brain and mouth. ‘Oh, OK,’ I said, mirroring my mother’s breezy tone. But this was only one incident among many that erected a strict scaffolding of gender rules inside me. Gender segregation was so embedded into the fabric of life that it was impossible not to internalise it and believe it was utterly normal. In mosques, men and women prayed in separate areas; in many Muslim countries, even the form and methods of prayer change depending on your gender. And when it comes to secular activities, the Middle East can be remarkably homosocial (you could say ironically so).

Like schoolchildren separated into queues of girls and boys before PE, my parents always split up when entertaining guests at home. My mother drank tea and smoked with the other wives in one room – all of them trampling over each other to show off the most recent designer pieces, as though it was some label-obsessed Lord of the Flies – while my dad and the husbands claimed the larger room, where they puffed on cigars and gambled. When my brother and I were ‘lucky’, we were invited to the pews of masculinity, giving us an insight into the cunning rules of poker – ‘lying to make money’ I called it – and tuning our ears to conversations about business (also lying to make money). Ramy clearly felt privileged to have access to this space, and wherever possible would initiate poker games with his own friends in a classic case of social reproduction, all of them future Arab homeboys in the making.

One night, when the whisky-scented card game was drawing to a close, I excused myself to go to bed. As I made my way, I hovered by the corner of the women’s quarter, peering in to get a glimpse of a world with which my heart felt more aligned. This was a room to which I needed the key; each guest was decked in enough jewellery to make the collective room feel like a vault at Gringotts (yes, I like Harry Potter), and textured fabrics of the richest emerald, sapphire, and ruby hues. The conversational mannerisms were dynamic and poetic. I watched with wonder as my mother entertained her guests, how she conducted their laughter as if the room were an orchestral pit, channelling an energy diametrically opposed to the square masculinity next door.

My mother’s Middle East was the one I felt safe in; this was especially the case the more Islam dominated my life. As a child, I was taught to be extremely God-fearing, and Allah, in my head, was a paternalistic punisher. He could have been another man at the poker table, but one much mightier, more severe than the ones I knew, one who might put his cigar out on my little head.

From as early as I can remember, I was forced to attend Islam class every week at school. When I got to Bahrain, the lessons went from warm and fuzzy – where Allah was a source of unending generosity and love – to terrifying, forcing open a Pandora’s box I’ll never be able to close completely.

At each lesson, the other children and I sat jittery at our desks and looked up at the Islam teacher. Her ethereal Arab robes cloaked stern arthritic hands and the billowing black fabric affirmed her piety. Her warnings about Allah’s punishments were grave. We were taught that throughout our lives, any sin committed would invite a disappointed angel to place bad points on our left shoulder, while any good deeds would allow an angel to place rewarding points on our right. Sins were remarkably easy to incur, and could stem from the most natural of thoughts – I’m jealous of that girl’s fuchsia pencil case – while good deeds were nearly impossible to achieve at such a young age, and only counted when you made an active, positive change in the world, like significantly helping a homeless person (a hard task for any seven-year-old). Sins, Islamic class taught us, hovered everywhere around us, and we had to do whatever possible to avoid them. Any time a slipper or a shoe faced its bottom up to the sky – an unimaginable insult to Allah – we’d be hit with a wad of negative points (it’s important to note that many things we know to be sins were inherited from cultural traditions rather than the Quran). And so, once I moved to Bahrain, I developed a compulsive habit of scanning any room I entered for upside-down footwear; I’d sprint around houses like a crazed plate-spinner, burdening myself with endless bad points for having got to each piece of footwear too late. These upside-down shoes would cost me up to fifty sins a day, each one a hit of fiery ash from the cigar above my head. Till this day, in fact, I still turn over any upside-down slipper or shoe that I find. And as a young child, I felt so desperate for these elusive positive points on my right shoulder, that at one point I decided I would be a policeman when I grew up, so as to make a career out of acquiring good deeds (little did I know of institutional police corruption).

The consequences of a heavier left shoulder were gravely impressed upon us. In short – as a sinner, you were fucked. Each week in class, we were made to close our eyes and imagine ourselves in the following situation: an earthquake tearing open the earth on its final day, forcing all corpses to crawl out of their graves and travel to purgatory for Judgement Day. Here, Allah would weigh our points in front of everyone we knew, who would come to learn all our sinful thoughts about them. And of course, if one incurred more sins than good deeds during one’s life, the only result was an eternity of damnation in Satan’s lair. As in any gay fetish club worth your money, the activities on offer include: lashing, being bound in rope, and humiliation – except none of it is consensual, it never stops, and you’re also being scalded with fire the whole time. Twenty years since being taught these torturous visual exercises, I am still subject to a recurring nightmare where Allah himself has pinned me to a metal torture bed surrounded by fire, and incinerates my body as he interrogates me for all my transgressions. Around twice a week, this nightmare wakes me up to a bed pooled in sweat (and, weirdly, once in a while, cum).

My left shoulder quickly outweighed my right in points. Of course there were the everyday misdeeds – my brother is annoying me, this food is dry, I think my cousin smells – that occupied my sin-charting angel, like a passive–aggressive driving instructor totting up minor faults. But there were also the major indictments. For instance, at the age of nine, as I was daydreaming in a lesson, I unthinkingly drew the outline of a bum on the Quran – thereby committing the ultimate defacement and simultaneously betraying an unconscious association between anal sex and religion that’s probably straight out of the psychoanalysis textbook. This blasphemy was a crime of such gravity that there was an entire school inquisition, with all the kids in my year group forced to produce writing samples. There I was, sitting on the sizzling hot concrete outside the headmaster’s office, trying to figure out how many good deeds I’d need to settle the insurmountable difference, yet also plotting to botch the test to get another child in trouble.

I got off the hook. After my writing sample was checked, I was told I could go home. On the bus back from school, I remember staring at the sandy pavements, and being struck by how many heavy rocks and boulders there were lying