ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

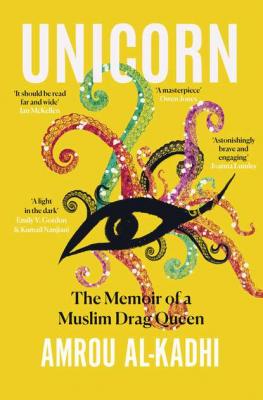

Unicorn. Amrou Al-Kadhi

Читать онлайн.Название Unicorn

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780008306083

Автор произведения Amrou Al-Kadhi

Жанр Религия: прочее

Издательство HarperCollins

For the twenty-fourth night that August, I found myself crossed-legged on the floor of a damp, pungent dressing room. As the rumblings of an Edinburgh crowd reverberated from the venue next door – I say venue, it was more like a cave – I used my little finger to apply gold pigment to my emerald-painted lips. Denim, the drag troupe that I set up seven years earlier, had survived the gruelling Fringe Festival, and we were one show away from crossing our scratched heels over the finish line.

A month of performances, often two a day, had taken its toll. My skin was at war with the industrial quantity of make-up it was being suffocated in (a two-hour procedure each time); I had obliterated my left kneecap because of a wannabe-rockstar ‘jump-and-slam-onto-the-ground’ move I felt impelled to perform each show; and a boy I was seeing had suddenly disappeared on me (I secretly hoped that death, instead of rejection, would be the explanation, but it turned out he was a ghost of a different sort: he had indeed stopped fancying me).

Despite feeling so weathered, I was itching to get onstage again. I always feel empowered when I’m in drag and entertaining a crowd – it’s my sanctuary, a space where I invite the audience into my own reality, where I don’t need to adhere to the rules of anybody else’s. No matter how low I’m feeling, the transformative power of make-up and costume is galvanising; for most of my life I’ve felt like a failure by male standards, and drag allows me to convert my exterior into an image of defiant femininity. This particular show was always exhilarating to perform, because it was the first time I honestly articulated my tumultuous relationship with Islam onstage, trying to mine humour in the unexpected parallels between being queer and being Muslim. How I haven’t been hit with a fatwa yet, I do not know.

A student volunteer usher told us we were moments away from the start of the show, and I did my pre-show ritual where I box with the air and shout ‘IT’S GLAMROU, MOTHERFUCKERS’. It comforts me to imagine my haters as the punch bag ‘motherfuckers’. Then I formed a circle with my other queens, our hands all joined at the centre in a moment of communion. The synth chords burst through the speakers, and the audience whooped as we strutted through a blackout onto the stage, our backs facing the crowd, pretending that the actual sight of our faces would be some sort of reward. A suspended beat, then lights pummelled the stage. I thrust my arms above me as if it were Wembley (I won’t lie; it usually is in my mind), and eyed the dripping condensation coating the cave ceiling, one drop a moment away from plopping on my face. After a prolonged and hyperbolic musical introduction – allow a queen her fifteen minutes – the show began with each of us turning to face the crowd one by one, until I pivoted around last. The next part was supposed to be me proclaiming ‘I AM ISLAM’, followed by the Muslim call to prayer remixed with Lady Gaga’s ‘Bad Romance’.

But on this final night, as I opened my mouth to start the show, I felt a little bit of sick at the back of my throat, and I found I couldn’t make a sound. Six Muslim women, the majority wearing hijabs, were sitting in the front row. There, looking directly up at me, were multiple avatars of my disapproving mother, about to remind me how shameful I was.

The ensuing performance was about as fun as your parents walking in on you having sex, and then staying to watch until you come. For a section in the show I sang a parodic ‘Why-Do-You-Hate-Me’ type number to my ex-boyfriend – but the boyfriend I was singing to was Allah. Throughout the routine, the women in front of me were using Allah’s name in a more God-fearing way – ‘Allah have mercy’ (in Arabic) seemed to be the most common refrain. Another highlight included a sketch in which I compare men praying in mosques to gay chemsex orgies. When I dared glance out in front of me, the mother of the group seemed to be repenting in prayer on my behalf. I started to ricochet around a mental labyrinth of paranoia, the censorious voices from my childhood chattering loudly in my mind. As my past enveloped me, the empowering armour of my drag began to dissolve rapidly. I stumbled over my lines, tripped on my heels – more than once – and even welled up onstage (which caused the eyelash glue to incinerate my cornea). The rest of the drag queens – as well as the audience – were white, so it felt as if the Muslim women and I were operating on a different plane of reality from everyone else, one where only we knew the laws.

Once the show finished, I sprinted backstage and threw up in a bin. My agent knew something was up and ran to the dressing room. I trembled as she hugged me, distressed at the offence I knew I’d caused. I felt like I was fourteen again, when my parents would tell me on a daily basis that my flamboyance was the root of their unhappiness. I’d worked so hard to create my drag utopia, and until that night, it had been my haven.

And then came the news I was dreading. The women, waiting outside the stage door, passed on a message to the usher: they wanted to see me.

Like a reincarnation of my teen-self, I shuffled off outside, with all the strength of a young seahorse adrift on an ocean current. Seven years after drag had liberated me, I was about