ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

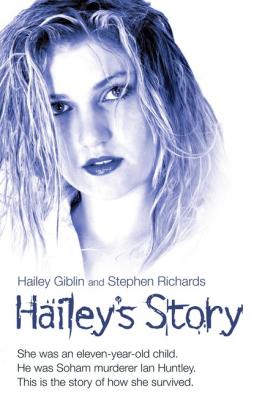

Hailey's Story - She Was an Eleven-Year-Old Child. He Was Soham Murderer Ian Huntley. This is the Story of How She Survived. Hailey Giblin

Читать онлайн.Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781782192589

Автор произведения Hailey Giblin

Жанр Биографии и Мемуары

Издательство Ingram

When the girls belittled Geri, I was able to equate my position to hers. I felt I was defending myself when I was defending Geri. I felt my alter ego was Geri Halliwell and, by proxy, I was able to stand up for myself. In a way I felt obliged to defend Geri and I even sympathised with her – not that she would have batted an eyelid at the scorn these schoolgirls showed towards her. I often wondered what would happen if she were to pay a surprise visit to the school. I could just imagine the two-faced traitors licking up to her and gushing through false smiles and gritted teeth, ‘Oh, Geri, we buy all your records. We love you, Geri.’

And I wouldn’t let these same people get away with saying I was useless at netball. I did defend my ego, as that is what I am: a defender. I was able to stamp my authority on the game not just by winning but by scoring good points. By playing better and by proving to myself, rather than to others, that I was capable of achieving my own goals.

My ability to bounce back at this age was inspirational to me and spurred me on. I was young, vibrant and full of life. Just because someone would suggest that I wasn’t good at something wouldn’t put a damper on it. I wouldn’t think, You’ve kicked me, I am down. I would think, I am getting back up, I am going to respond to that with my actions; I am going to show you that I am able to overcome adversity.

This wasn’t just so that I could prove my resilience to others, not to prove them wrong or whatever, but to prove myself right, to prove that if I put my mind to something I could do it. It needn’t have just been about netball, although that is what I have drawn on as an example.

I believe it was my family, in various ways, that helped me challenge those who said I was no good. They have never pushed me forward with calls of ‘Come on, girl, we will support you in whatever you do.’ I believe it is as a consequence of this lack of support that I have overcome certain put-downs. I am my own person. If I want something I won’t rely on anybody to get it for me. I will go out there and work damn hard to get it myself so that people who may want to judge me can’t say, ‘She wouldn’t have that if it wasn’t for me.’ I want to be able to stand on my own merits.

I wasn’t born with a silver spoon in my mouth. Anything I get, earn or achieve is something that I have done myself. Whether that is as a direct result of mirroring my mum’s efforts in working all hours and seeing what she can achieve, and she has bounced back from some tough situations, I don’t know. But I do know that, when I reach 40, I don’t want to be just a wife and a mum.

This determination isn’t something that was instilled into me as a child. This is something that I just put into myself, thinking, I don’t want to just be an ordinary mum. What could have influenced this belief was that my granddad always said that when I walked into a room everybody would look at me. ‘Your eyes sparkle and everybody’s face lights up,’ he told me. ‘You’re special.’

I would like to think that I could influence people for the better. What my granddad told me, all the good things and all the praise, I feel that it did, in fact, work. Without that praise, without being patted on the back, ‘Good girl, you have done well,’ that effect on me may not have happened. I can say with certainty that my granddad’s influence came through to me and made me a stronger person, but not straight away. It was something that permeated me slowly, that took time to mature to what it is today.

Self-praise is no praise. I can thank Granddad for showing me that. I remember how I would create something at school, maybe something I never really held aloft as a work of art, but Granddad would give a knowing look and cast his discerning eye over it and say, ‘Oh, can I have that, please?’

That’s how he was able to lay the foundations within me for the road ahead. I would say, ‘Look at what I’ve done at school today, I have done this mosaic.’ Of course, when Granddad asked for it, I used to think, Why, is it that good that he wants this on his fridge? It has got to be good, that’s great. He would go on about the creative arts and making things.

Granddad had this pot – I think Mum has got it now – it was just a clay pot that I made. Everybody else was just making a normal bowl, but I made a square one, and it was really good. I would even be proud of it if I were to make it now. I cut out little leaves, made marks on them and put a row of them all the way around it. Then I painted it black, with the leaves in green. I was quite proud of that. Granddad ended up keeping it and I think when he died Mum put it in the cabinet.

Another time, when I was about 12, we were asked to look at something and be inspired by it. The art teacher just put a load of objects together – a clothes iron, some thick chain, a flower and other things – and said, ‘I want you to draw what you see. Draw an impression of what you believe it represents.’ He added, ‘Don’t just look at a picture, look deeper into the picture.’

My picture was massive, all bright colours, with the chain going right across the page. Mum’s friend Dawn opened a café in Freeman Street and the owner’s son did a similar painting and put it up in the café. Then she asked my mum if she could put my picture up, and she said no.

Mum had a nice frame and glass put on the picture. Then and there, the framer offered her £900 for it. Mum praised the work, cooing, ‘That’s what my daughter did in Year Eight.’ When she came home she gushed, ‘You know that painting, the man that I took it to said he would buy it for £900.’ At the time I was cock-a-hoop and squealed with delight at the prospect of being rich. ‘Oh, and are you going to sell it so that I can have some money?’ I asked.

‘No!’ said Mum.

To this day the cherished painting hangs in Mum’s house. I wasn’t particularly inspired by any Impressionist painter, and to this day I have never painted another thing like it – it was a one-off. I didn’t have an urge to go to art school or the like. I have got to be 110 per cent interested in something, because, if you are only 90 per cent interested, what’s the point?

My hidden artistic talent was never applied to anything more than normal paintings that were just stuck on the fridge. But that Impressionist picture is quite inspired, and you wouldn’t think I had created it. Whether it represented something in my life at that time, I don’t know. Perhaps I was trying to reveal the brighter side of me, because I felt quite dull then. Maybe it represented something in my experience that I was only able to interpret artistically.

You could call it an Expressionist piece, because it was able to express what I couldn’t put into words. In trying to find my thoughts from that period, I came up with: Everyone in this world has got friends and I am on my own, so I will paint this.

I used bright pink and yellow when everyone else was using black and dark green. As I look back, I think in that painting I brought out the way I was feeling then. My strong colours represented a lot of aspects missing in my life, and I was able to use art in a therapeutic way. It embodied everything that I felt I didn’t have at that time: vigour, energy, power.

At that period in my life, everything seemed so uninspiring. This is why I looked at myself for inspiration; it sounds narcissistic, but I wasn’t in love with myself. I felt that I was leading a humdrum, repetitive existence: school, home, homework, school. My escape from it all was to look at the Spice Girls as an example of what could be done to change your life. They were full of vigour and pep, particularly Geri Halliwell; she was the embodiment of all that I wanted to be. I felt I could have been her, so I defended her.

I liked Geri so much that, when we did a talent contest at Cloverfields Primary, I performed as her after getting together with some other Spice Girl wannabes. We had a month to rehearse as the group we wanted to be or to work at portraying a solo singing star. I enjoyed singing and I was doing Geri Halliwell’s bit of ‘Who Do You Think You Are’. So, in a way, I became my idol. I had my hair done and threw myself into the role when we performed on stage in front of the whole school.

A few years later, when I was about 13, I sang Mariah Carey’s ‘Hero’, a solo song. I put a great deal of preparation into that role. I prepared myself