ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

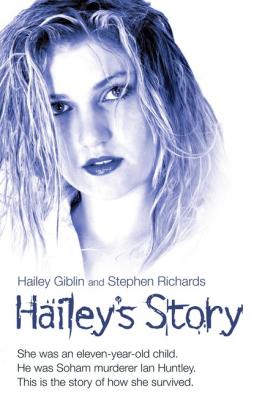

Hailey's Story - She Was an Eleven-Year-Old Child. He Was Soham Murderer Ian Huntley. This is the Story of How She Survived. Hailey Giblin

Читать онлайн.Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781782192589

Автор произведения Hailey Giblin

Жанр Биографии и Мемуары

Издательство Ingram

Just as Huntley admitted, in a police interview, his sexual misconduct with a minor, so did Newell. The court also heard how the twice-divorced caretaker lured children other than the girl into the school at weekends when it was empty.

Sentencing Newell to a paltry three years behind bars, Judge William Gaskell said, ‘You are going to prison. You will now have to expect that you will not be around for a long time.’ Incomprehensibly, the judge even bailed Newell over the weekend in what he termed ‘an act of mercy’ that would enable the convicted man to speak to his elderly mother before being locked up. What act of mercy did the evil Newell show his young victim?

The same errors that allowed Huntley to kill also allowed Newell to destroy a little girl’s life. No lessons at all had been learned from the Soham murders.

Hailey’s cries of pain and anguish when she claimed in the summer of 1998 that he had ‘raped’ her some months earlier were felt to be insufficient by the police to prosecute on. If only Huntley had been stopped then.

Although the 12-year-old’s innocent definition of rape was different from an adult’s, Hailey had indeed been sexually assaulted in a nightmarish and drawn-out ordeal. Over several hours, Huntley repeatedly sexually abused Hailey after luring her away from the safety of her street in broad daylight and taking her to a secluded orchard behind a pub.

Although the jailing of Huntley for murder would eventually come, for Hailey, one of his youngest victims, there was no court case and so no justice to bring to an end the pain and humiliation she had suffered at his hands.

On 16 July 1998, Sue Kotenko, of Grimsby East’s Assessment and Investigation Team, received from the police Form 547, which alleged Hailey had been assaulted by a 22-year-old man called ‘Ian’. On 5 August, however, Police Sergeant Tait decided not to prosecute Huntley, on the grounds that there was insufficient evidence for there to be a realistic prospect of conviction. Huntley’s bail was cancelled.

Seven months after Huntley’s conviction for the Soham murders, Sir Christopher Kelly’s North East Lincolnshire Area Child Protection Committee Report on the Huntley case, which covered the period 1995 to 2001, robustly criticised both the relevant police and social services for their incompetence. The Kelly Report of July 2004 revealed that a management review by social services acknowledged major concerns over the handling of the case. Further blame was laid firmly at the door of social workers for their failure to seek any additional information about Hailey at the time she reported Huntley’s alleged assault on her.

Also commented on by the report were the circumstances of the alleged sexual assault, including Hailey’s age, the location of the attack, its violent nature and the time lapse between its occurrence and its being reported. Together, Kelly stated, these should have generated questions in the minds of social services staff about the young girl’s welfare.

The report went on to say, ‘There appears to have been no attempt to consider MN [Hailey] as a potential or actual child in need in terms of Section 17 of the Children Act but rather to view the matter as an issue of crime detection.’ And it further shamed social services and police by stating, ‘Apart from anything else, alarm bells should have been rung by the circumstances in which the allegation came to light.’

Important as Kelly’s findings were, they provided little consolation for Hailey, whose peace of mind had been shattered by the destruction of her innocence. Despite this, and the consequent harm she inflicted on herself, she earnestly tried to rebuild her faith in life by eventually marrying the man who had become her saviour when she ran away with him at the age of 15.

In a blaze of publicity, Hailey Edwards wed Colin Giblin, then 37, in Humberston, Lincolnshire, less than 18 months after Colin faced charges of unlawful sexual intercourse with the underage Hailey. What might have been merely an escape route from the pain of a stolen childhood seemed to Hailey a divine intervention, rescuing her from the hell she had endured.

Here was sanctuary and security in the arms of a man she trusted and loved. Yet the hell was to continue a little longer after Colin, having admitted unlawful sexual intercourse with Hailey, was, bizarrely, placed on the Sex Offenders’ Register. After two weeks, when police accepted that he shouldn’t have been on the register, his name was removed.

Here was the very essence of what love was all about being sullied, when the real cause of Hailey’s living hell had been the subject of a whole raft of allegations of sex crimes that had been made known to the police and social services before the tragedy of Soham.

What of Huntley during the years that Hailey was hoping for justice? From July 1999, he seems to have gone to ground until he resurfaced in the Cambridgeshire village in 2002, with Maxine Carr (originally Capp).

It was on Sunday, 4 August that year that best friends Jessica Chapman and Holly Wells walked to a sports centre near their homes to buy sweets. The two ten-year-olds would not be seen alive again.

When the trial of Ian Huntley and Maxine Carr began at the Old Bailey in London on 3 November 2003, Huntley was seen as the primary culprit in the murders. After telling the court how he ‘accidentally’ killed the two girls, the accused said he tried to conceal the truth from his family, Carr and the police because of his shame and fear of not being believed.

Both Huntley and Carr were considered convincing liars and it was claimed in court that the girls ‘had to die’ in order to serve Huntley’s own self-interest.

On 17 December 2003, the jury returned their verdict. Carr was found guilty of conspiring to pervert the course of justice, yet she was cleared of two counts of assisting an offender. She received a prison sentence of three and a half years.

After rejecting Huntley’s story, the jury found him guilty of the murder of Jessica Chapman and Holly Wells. He was sentenced to two life terms in prison.

Another 18 months of waiting passed for Hailey Edwards and then, on 8 July 2005, following a further review of Huntley’s alleged sex attack against Hailey eight years earlier, Catherine Ainsworth, a lawyer with the CPS in the Grimsby office wrote to advise her that they were not pursuing him over the matter. The three-page unsigned letter brought no comfort to Hailey as she read the lawyer’s stark words: ‘I have reviewed all of the evidence against Ian Huntley and have decided that there is not enough evidence to proceed with this case…’

Clearly, in reaching this decision, the CPS did not look at past allegations against Huntley or at the persuasive way in which he had lured Holly and Jessica to their deaths – much as he had sweet-talked Hailey into going to ‘climb trees’ when he had something much darker in mind.

And then, on 29 September 2005, the High Court set a 40-year tariff for Huntley, which means he must serve at least that length of time behind bars before even being considered eligible to apply for parole, by which time he will be almost 70.

Understandably, Hailey feels let down by Catherine Ainsworth’s decision on behalf of the CPS. Consequently, she plans a civil prosecution against Huntley to prevent any attempt by him to gain freedom through gaining parole after serving his 40-year tariff. Here, in her own words, is Hailey’s story.

WHEN THE SUN SHINES, EVERYONE IS HAPPY

ON 16 APRIL 1986, I WAS BORN IN THE FISHING PORT OF GRIMSBY. When I was delivered, in the Princess Diana Hospital, I weighed seven pounds and ten ounces, a little bundle of joy. I am the only girl of six children born to my mother. I have two younger brothers and three elder, all born in Grimsby.

By today’s standards, if you go by the early-morning TV misery shows, my broken-home family of mixed-parentage siblings was quite normal. When my mum, Amanda Jayne Brown, was 16 she married