ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

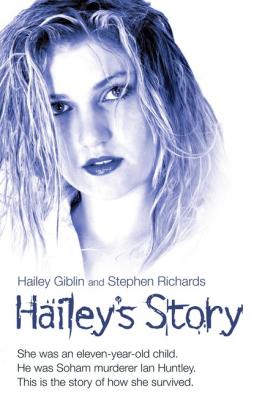

Hailey's Story - She Was an Eleven-Year-Old Child. He Was Soham Murderer Ian Huntley. This is the Story of How She Survived. Hailey Giblin

Читать онлайн.Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781782192589

Автор произведения Hailey Giblin

Жанр Биографии и Мемуары

Издательство Ingram

He would proclaim with gusto, ‘Well, I’m going to have fish,’ and, as he looked expectantly at my mum, he would ask, ‘What are you going to have, Mandy?’

Mum would pick herself a mouth-wateringly tasty piece of fish from what was on display in the hot, glazed servery and, in turn, ask, ‘What do you want, Hailey?’

Shivering with excitement, I would gather my thoughts and say, ‘Can I have a small sausage, please, with chips?’

Within minutes my order would arrive in the safe hands of a waitress: two massive sausages, some big, fat beefy chips, peas, gravy and a thirst-quenching glass of orange juice to wash it all down, all accompanied by doorstops of bread and butter. It was a magical experience that words can’t fully capture. ‘Wow’ might be the best word to describe it. And yet, from the outside, the place was nothing special. It was on the corner of Freeman Street, in Grimsby: a brick building with two windows. We used to sit near the window at the far end. The place had a strange sort of sliding door; and it was narrow, so only one person at a time could squeeze in.

We would go in and Granddad would announce regally, ‘A table for three, please.’ They would show you to a little high-sided booth. The booth was like Santa’s sleigh: it instilled a feeling of sanctuary, even of womb-like security. That cafe, with its ‘olde worlde’ charm, meant a lot to me. There I was protected from all the evil in the world. So it meant more to me than just being ushered to our booth and sitting there, Mum, Granddad and I. I don’t recall Grandma ever coming with us on a Saturday.

Afterwards, we used to have a gentle stroll around the wondrous marketplace and, to keep me contented for the trip home, they would buy me a small bag of sweets.

That’s my special memory of the Pea Bung, an enchanted place that remains in my thoughts; a place that offered warmth, security and comfort. If I could wish myself back to anywhere in the world, that would be it.

The reverence I felt for it was destroyed, though, if anybody else came along with us, including my brothers. They were infringing on my special place, and it would infuriate me. This was my special world, and I would think, Don’t you know, you shouldn’t really be here. This is my place with Granddad and Mum.

I knew I was Granddad’s favourite; he always called me special. I like to think so, anyway, because there were so many of us children. He used to give everyone else a normal-sized birthday card or Christmas card but, when it came to my birthday or Christmas, I would get a really big one from him and he would always write inside: ‘To my darling Hailey, hope you have a wonderful birthday, my special girl, love from your Funny Granddad.’

We called him ‘Funny Granddad’ because he was a witty and amusing man. Everything he used to come out with was funny; he was just that extraordinary type of person.

As much as I would describe the Pea Bung as my sanctuary, I would describe my grandfather as my rock. However, nothing is forever, and, at 14, my world was to collapse soon enough. I remember being near the front door, when we lived in Glebe Road, in Humberston, and my cousin Keeley burst in, her face ashen. ‘Where’s your mum, where’s your mum?’ she wailed. She was crying her eyes out and in that split second I knew what had happened.

Granddad’s death was a shock to us all: he wasn’t ill and it was so sudden. He had a lady friend who lived around the corner and they used to go out shopping or he would go and have a natter and a cup of tea with her. From what I was told, he went round there one day and he was sitting in the front room having his regular cup of tea when he said to her, ‘I don’t feel very well, can I go for a lie down?’ So he went and lay on her bed and, when she went to see if he was all right, he had died. He was seventy years old. My rock had crumbled.

That morning, before Granddad died – I think it was a Friday – Mum had mentioned going out for fish and chips at the Pea Bung. Mum had bought another house, as our finances were better, and she was planning on going there that morning to do some work. So it was a big surprise that she was thinking about taking Granddad to the Pea Bung, and I was under the impression that I might be able to go there this time. Sadly, it wasn’t to be.

Since then, my memories of the Pea Bung have been tinged with dark clouds of sorrow, but fond rainbow-coloured memories still shine through like shafts of sunlight on a stormy day.

Many years later, I plucked up the courage to make a pilgrimage to the Pea Bung. My visit conjured up a mixed bag of memories. In a way, I felt proud of the cosy little place. Still there were the protective booths, the seats, the funny little door. One other thing I recall is that they had this unusual wooden spoon bearing the words ‘Don, the world’s biggest stirrer’.

I used to quiz Granddad about this. ‘What does that mean?’

Amused, he would throw his head back and say with a laugh, ‘I’ll tell you when you get a bit older.’

I couldn’t wait for the secret of the spoon to be revealed to me. Mum used to say that it was because he used to stir up trouble with all the little old ladies behind the counter and pull their leg and tell them jokes and try to mess about by saying things like, ‘Well, she said this about you,’ and they would go, ‘Did she, really?’ and then he would say, ‘No, not really.’ So they got a big spoon and put it on the wall for him.

Then, when we went back not long ago, I was devastated to see that the place I once worshipped had been changed. Its whole sanctity had been disturbed. The essence of what the Pea Bung was all about seemed to have been lost. Gone were the special Santa’s sleigh seats, all knocked out and replaced with new seating. I felt quite uncomfortable. It sounds silly, because it was only a fish and chip shop, but it wasn’t special any more, like it used to be. The charm had gone.

But I still ordered two sausages, chips, peas and gravy, a glass of orange juice and some bread and butter. Mind you, there was a small consolation when I was approached by some of the staff – half of them I didn’t even know – and they declared, gobsmacked, ‘You’re Don’s granddaughter!

‘How old are you now?’ they asked.

Then someone said, ‘I remember you when you were six years old, sitting there, when you knocked over your glass of orange and the look on your face was just like “Oops”.’

‘Oh, did I?’ I said.

They all remember me, although I don’t know them. You can guarantee that every time I set foot in there they will go, ‘Your granddad was called Don, wasn’t he?’

‘Well, I’ve never seen you before but yes he was, yes,’ I say.

On that first return visit, I had a feeling of loss when I looked around for Don’s ‘stirrer spoon’ and it wasn’t there. I asked where it was and if I could have it, and they told me, ‘Come back when we have sorted the shop out and you can have that.’

The lady said it had been taken down only about three or four weeks earlier, because they were changing everything around. When I went back again, they had clearly made the changes to the place, but the spoon still wasn’t there. And that was that.

That day Granddad died, Mum and I were alone in the house after Keeley had left. Mum sat on the stairs crying her eyes out, and I was crying beside her. I reached out and put my arms around her. I felt enormously upset, as if my world would explode in a million pieces. It was just Mum and I. So I thought, Well, I’m going to look after her because nobody else is here. That is the feeling I think I had from that time on.

Losing my granddad in my early teens had an overwhelming and disturbing effect on me. The loss of such a strong alpha male from my life left a void, a chasm so hollow that even the moon could not fill it. I ached and ached until there was nothing but hollow numbness within me.

Granddad made me feel safe; he was like a best friend. I couldn’t do anything to disappoint him. Whenever I was around him I was always good and behaved myself, but out of respect, not fear. He insulated me from the