ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

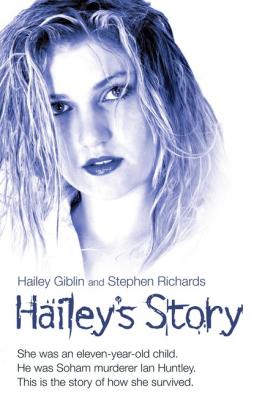

Hailey's Story - She Was an Eleven-Year-Old Child. He Was Soham Murderer Ian Huntley. This is the Story of How She Survived. Hailey Giblin

Читать онлайн.Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781782192589

Автор произведения Hailey Giblin

Жанр Биографии и Мемуары

Издательство Ingram

Not one to be daunted by the prospect of a scalding, I kept suggesting that I make them a cup of tea, so when I got a little bit older and more able – I think I was about ten – I was allowed to. I skipped into the kitchen, joyful at the prospect of making my very first pot of tea. After I became competent, I would take an early-morning cup up to my mum in bed, and a coffee for my dad.

Mum would get up, put on her dressing gown and come downstairs and tidy up, whereas Dad would end up falling back to sleep and leave his coffee there to go cold for an hour. I would go to my bedroom and he would call out, ‘Hailey, do me a favour, duck.’

‘Yes, what’s the matter?’ I would ask enthusiastically.

‘Will you make me a fresh cup of coffee? I’m sorry, I forgot that one,’ my dad would groan.

‘Yes, all right then,’ I would chirp.

But after a couple of weeks I got bored with making hot drinks and Dad wasting his. So in the end, when he kept saying, ‘Will you make me a fresh cup of coffee?’, I would put on the kettle and while it was boiling I would place the cold cup of coffee in the microwave for 30 seconds to heat up. With the kettle boiling, they couldn’t hear the noise of the microwave. I only told him about a year ago that I used to do this. I was a fast learner.

Although I was always looking to please people and was doing well at school, I always fell short of pleasing my mum in the sense that I didn’t make her totally happy. Her disappointed outlook on life I put down to the fact that she may not have been wholly happy with her own lot, as she was really stressed with work. Mum is a workaholic.

Her job was as a care assistant, working in an old people’s home all hours of the day and night. On reflection, I suppose juggling your life between work and your husband and six children must have been a bit of a balancing act. As a grown-up, I can see that nothing makes my mum happy. I don’t want to sound like I’m attacking Mum’s integrity, as she did congratulate me on my academic achievements, and she did attend school from time to time to see my work. But my gaining these qualifications didn’t really please her in the way I felt it should have done.

In a way, I felt Mum never really supported me enough with homework, with subjects like maths. I used to enjoy maths until I was ten or eleven years old, but after that people used to say, ‘You don’t like maths, do you?’ I would steadfastly defend myself, ‘Yes, I really like maths and my maths teacher and everything.’ I used to go home with homework and Mum used to say, with defeatism in her voice, ‘Go and ask your dad… I’m not great at this, but your dad is good at maths.’

So Dad would sit there and say, ‘I’ll do it for you,’ and he would do the work for me. But I look back on this now as the easy way out. You are supposed to say, ‘Sit down and I will read the question out and you try and work out the answer,’ instead of having someone else just write it down for you.

Mum was very busy with her work and I was the only girl. I felt that my brothers got everything and that my being asked to make the tea for everyone was a poor consolation prize. But then, for a while, things changed and for a good few years Mum and I became best friends and developed a loving relationship; we were inseparable.

Dad and Hayden used to do the father-and-son bonding routine of going to the football on a Saturday. Mum would get a can of Coke and a bag of bonbons and the two of us would sit there and watch repeats of EastEnders, do each other’s hair or go out shopping. That’s the sort of thing mums and daughters are supposed to do together, isn’t it?

As I became older and more self-reliant, I fitted in with Mum’s routine. At that stage I didn’t feel neglected.

In trying to recall a spontaneous memory from that time, I remember the times I would be out in the street near to home. It’s in part simply a fond memory and in part a growing-up memory that shows how I was starting to think for myself. The ice-cream man used to always come about ten minutes before teatime. Often Mum would comfort me by saying, ‘You can have an ice-cream tomorrow night, OK?’ and then, ‘Go on, you can go and play outside for ten or fifteen minutes and I’ll shout for you when your dinner is done.’

Of course, I would catch sight of the ice-cream van and without hesitation I would saunter up to the van. Feasting my eyes on what was on offer, I’d have the brazen brainwave of saying to Don, the man serving, ‘Oh, yeah, my mum hasn’t got any change today, but she said, if she gives you the money tomorrow, could I, you know, have a cornet?’

Don would give in and say, ‘Go on then, I’ll give you an ice-cream.’

As I recall this, I remember how much I wanted that ice-cream. I wanted an ice-cream that minute, there and then, not tomorrow. That was as far as I pushed the boundaries of innocence as a child. I knew no different, but it shows how childhood innocence was looked upon by the ice-cream man.

I pulled that ruse quite often, but then Mum and Dad cottoned on and they would come out to the van and say to Don, ‘Did Hailey have an ice-cream last week that she forgot to pay for?’

Don would innocently reply, ‘Well, actually, she had about four’ as he looked at me with that ‘You’re not supposed to do that’ expression on his face.

When I got a little bit older, I used to do the same thing but the very next day, when the ice-cream man came, my mum would give me the money and I’d say to Don, ‘Oh, there’s the money for your ice-cream.’

I would say to Mum and Dad, ‘Oh well, I don’t want one tonight because I used the money for today’s,’ and they would say, ‘Well, go on and have one anyway.’

Something that happened not long ago made me recall this particular memory. We went for a day out to Hemswell Market, where I used to go shopping with my granddad on a Sunday. I walked past an ice-cream van and I saw this guy inside and, to my utter astonishment, it was Don. It was the same ice-cream man, in the same van, and it brought the memories flooding back like a burst dam. And didn’t it seem as if time had stood still? I was just standing there thinking, God, how strange is that after all these years?

I went straight over and said hello to him. To my amazement, he remembered who I was. He was like, ‘God, I haven’t seen you in ages. You look so grown up now. You’ve cut all your hair off.’ My hair used to be down past my waist. It was like I had accelerated all these years forward to where I was now. God, if only that had been possible! I just stood there and I had a lot of fiery flashbacks. All these disjointed memories came flooding back.

That brings me on to a memory tinged with both happiness and sadness that was brought on by the memory of going to the market with Granddad. When I was still in primary school, on Fridays my mum used to go to this fish and chip restaurant with her dad, Granddad Don, and Grandma. The place had the peculiar name of the Pea Bung – that’s what Granddad used to call it, anyway. ‘We’re off to the Pea Bung on Friday,’ he would pipe up.

When my mum got back I would eagerly ask, ‘Did you have a good day, Mum?’

With a twinkle in her eye, she would reply, ‘Yes, guess where I’ve been.’

‘Where?’ I’d say.

‘Go on, have a guess,’ she would challenge me.

Feeling I’d been left out, I would ask dejectedly, ‘You haven’t been to the Pea Bung with Granddad, have you?’ Because as a child it was my favourite place.

Mum would bring me down but then lift me up by answering, ‘Yes, I have, but next week we’ll go, and we’ll go on a Saturday.’

‘Can’t I go on a Friday?’ I would plead.

It was always, ‘No, you can’t, because you’ve got school, so we’ll take you on the Saturday instead.’

Still, the chance to go to the Pea Bung, even on a Saturday, was a treat beyond comprehension. The expectation of what lay ahead on Saturday would fill me with