ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

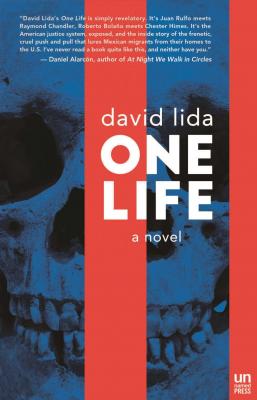

One Life. David Lida

Читать онлайн.Название One Life

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781944700249

Автор произведения David Lida

Жанр Триллеры

Издательство Ingram

“You can just say Ojeras,” said Juventino, “in the municipality of Puroaire, the state of Michoacán, in México.”

It crossed my mind that all this might have been an elaborate put-on. That Juventino was holding out on me, malevolently playing stupid for whatever reason he had up his sleeve: mistrust, perversity, petty revenge against Marta or Esperanza. But I looked into his glazed-doughnut eyes and my gut told me he wasn’t clever or willful enough to withhold important information. He just didn’t have any. Sometimes a potential witness can be a huge disappointment, but it’s rarely their fault. They would help you if they could.

I put a hand on his shoulder. “Thanks for your help,” I said.

“Para servirle,” he said.

I put my notebook back in my knapsack, the pen in my pocket. I stood up to leave.

“What did you say your name was?” asked Juventino.

“Richard,” I said.

“Can I ask you a question?” said Juventino.

“As many as you like.”

He scratched his belly. “Is she guilty?”

People frequently ask me that. Most of the time, the answer is “hell, yes,” but I would never say so. “I honestly don’t know, Juventino,” I said. “I wasn’t there. There are a few things in this case that don’t make sense. For now, I’m just trying to convince the prosecutor not to kill her. If we get death off the table, then there will be other options.” Life without the possibility of parole, for example. Staring at metal bars and concrete walls forever, even if she lives to be two hundred.

He nodded. “I don’t believe she killed the baby,” he said.

I held my breath. You never know what little miracle they might have up their sleeves. “What makes you say that, Juventino?”

He shrugged. “Because she’s good people,” he said.

I limped back to the taxi. The driver put the car into gear and we began the trip back. There is always a moment of exhilaration looking out that flyspecked windshield as a town disappears and you hit the highway. It took two and a half hours to get here and would be another two and a half to get back. Plus an hour in Ojeras, another to write up the memo. Seven hours: seven hundred dollars. Not a bad day, if I didn’t get rabies.

He is thick with solid muscle, a body so dense that Esperanza thinks he might burst out of his stiff sky-blue shirt like el increíble Hulk. Two days ago he told her his name was Shepherd. He leans toward her so his face is a couple of inches from hers. Veins pulsate at his temples: he may whisper or he may scream. She can smell the pharmaceutical cologne mixed with his sweat, the chemical grease with which he tames his wavy hair into submission, the tobacco on his breath. There are pocks and pores in his sallow skin, red veins in his hazel eyes. His right eyebrow twitches. He needs a shave.

“How did you kill the baby?” he says. He speaks as if the question had occurred to him suddenly, as if he hadn’t asked her 162 times over the past forty-eight hours.

Bobby, who is translating as well as transcribing the conversation, repeats the question in Spanish.

“I don’t remember,” she says in the tiniest of voices. Did he think she would say something else this time?

Shepherd’s partner sits across from Esperanza. Shepherd introduced him to her as the Blob. Jelly-bellied and bullet-headed, he executes a two-fingered drum roll on top of the table. Esperanza registers him as Louisiana brown: a café au lait moreno who can’t speak Spanish.

Straightening his body, pulling up his pants, snorting, Shepherd nods his head. “‘I don’t remember,’” he says, looking at his partner.

“She don’t remember,” says the Blob.

“You think she don’t remember?” he asks.

“She says she don’t remember,” says the Blob. He snickers and scratches his dome.

“You know what? I’m sick of hearing that she don’t remember.” Shepherd stares at Esperanza with boiling eyes. His hair is so black it is almost blue, like a character from a comic book. Bobby neither renders nor records the policemen’s patter.

They are in a tiny room with a scratched Formica table, four plastic folding chairs, and a mildewed gray rug that smells of heavy Payless shoes and the pavement they’ve beaten. Shepherd leans in until he’s an inch away from her eardrum and yells at the top of his voice, “How did you kill that fucking baby?” As a consequence of all of his screaming, Esperanza has a ringing in her ears that won’t go away. The Blob slams the flat of his hand on the table in front of her body, in case further emphasis is needed.

“¿Cómo mató al bebé?” drones Bobby.

“Tell them I don’t remember,” Esperanza says to Bobby. There are tears in her eyes. When they picked her up two days ago, she was drenched from the pounding rain. She has a fever. No matter how many times they scream in her ear or slam the table, it doesn’t get any easier. When is this going to end? When will they finally kill her?

“She doesn’t remember,” repeats Bobby.

Shepherd begins to pace the room in a slow circle. “Oh, man,” he says.

The Blob cracks his knuckles. “You having fun yet?” he asks.

“You think this is my idea of fun, you perverted Congolese boy humper?” asks Shepherd. “I’m a family man. How can you say sick shit like that?” He says to Bobby, “Tell her I got a three-year-old and an eight-year-old and I want to go home and see my kids.”

When Bobby translates Shepherd’s assertion, Esperanza thinks of tiny Yesenia, blue, cold, gruesomely disfigured, stiff as a baseball bat. She wraps her arms around her torso and weeps.

“Shit, we lost her again,” says the Blob. “Earth to Esperanza,” he yells, smacking his palm on the table to retrieve her attention.

“I’m supposed to feel sorry for her?” asks Shepherd to the air. He looks at her with disgust. “Sick bitch kills her baby and what’s she want me to do? Call up the social work squad? Take her out for a steak and a mojito?”

“She don’t have to remember,” says the Blob. “She says she done it. She came and got us. We can let the lawyers figure out the rest of it. Why don’t we let a sleeping dog lay the fuck up? It’s been two days.”

“She remembers how she killed the fucking baby,” says Shepherd. “Man, that kid was destroyed—burned, battered, and boiled. How can you do that to a fucking baby and not remember?”

“It’s been two motherfucking days! She’s a nutcase. If she remembered, don’t you think she would’ve given it up by now?”

Sniffling, Esperanza runs a hand up her sleeve and scratches her upper arm. Her legs and torso also itch. It’s as if the atmosphere were full of invisible fleas. When Shepherd and the Blob leave her alone, she curls up under the table and sleeps. She has been given no food or water since her arrest. She has not been allowed to make a phone call. She was advised of her rights to remain silent and to a lawyer. The first option went right over her head and Esperanza knows only rich people can pay for lawyers. “Rights” are, in any case, an abstract concept. She vaguely remembers hearing about them in school, but has no idea how they pertain to her.

“I’d rather give it back to the DA in a neat package,” says Shepherd. One of these days I’d like to get a promotion.”

“I say she would’ve given it up by now,” says the Blob. He smiles at Esperanza, gives her the once-over. “She sure is fine, though. Mmm-mmm. Too bad that shit’s