ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

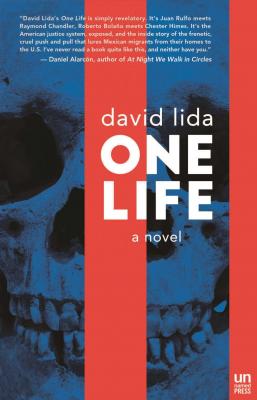

One Life. David Lida

Читать онлайн.Название One Life

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781944700249

Автор произведения David Lida

Жанр Триллеры

Издательство Ingram

The town plaza was so tiny you could fit it in your wallet. It was ringed with trees, which had been pruned into perfect little squares like green marshmallows on sticks. There were iron busts of four men—los hombres ilustres—local poets, professors, politicians. The clock in the church’s skinny spire read ten to three, 24-7.

Brown-skinned adolescents kicked a soccer ball despite the afternoon heat, wearing their caps sideways and pants that stopped at their knees. Two chattering girls barely out of their teens walked down the street, each pregnant. A lady in a blue apron waved the flies away from quesadillas she had fried in boiling oil for invisible customers, next to a white plastic table covered in a plaid plastic cloth. There were few men around. The absent were mostly in el gabacho.

The closer we got to the edge of town, the more primitive the houses became. Adobe or clapboard slats for walls, corrugated laminate for the roof. Sheets of torn plastic instead of windows. Bent, crooked doors fastened with a chain and a padlock, or with nothing at all. Finally we got to a huge crater covered in rocks and mud. It was a circle about three city blocks in diameter and fifty feet in depth, and it looked like the surface of an undiscovered planet. On the other side were more shacks.

“She lives up the hill there,” said the driver. “Sorry, but my car won’t get through that hole.”

“No problem. I’ll walk.”

Clambering through the stones and mud was my exercise for the day. I tried to walk around the brackish, soupy puddles, some of which glowed with a rainbow chemical swirl. I had to go back and forth only once. Poor Juventino’s mother had to do it day after day, if her son gave her any money for groceries.

I had high hopes for Juventino. He had been married to Marta, one of Esperanza’s older sisters. The promising facts were that he was not an actual family member, that he and Marta had split up years earlier, and that he lived in another town. He had nothing to lose, no one to protect, no more diplomatic duty to perform. If I was lucky, he would have axes to grind. A witness like that can spill all kinds of dirt.

By the time I had traversed the crater, my black sneakers were covered in mud. The huts were so ramshackle they looked like they’d fall over if you leaned against a wall. A dry, hot wind kicked up a whirlpool of dust. If dirt were expensive everyone in Ojeras would be a millionaire.

Four dogs lay in the middle of the road, in shades of matted gray and beige. Mama was mangy and bloated with milk, and had about nineteen nipples. Her boys were lean. I could see their ribs, the flesh rising and setting with their breath. As I got closer they started to growl. What could they possibly have been protecting? Was anyone actually hiding a stash of something inside one of those broken-down shacks? The wrong questions to ask in a Mexican Podunk.

They snarled more loudly as I approached. The smallest one, a disheveled silver mutt, got up and yapped at the top of his high-pitched lungs. Why is it that the tiniest dogs always sound as if they’d swallowed a microphone? He scampered to my side. “It’s okay,” I said in a velvety but stern purr. I was perennially hopeful an utterance like that would shut up a barking dog, but it never did. He only bleated more loudly.

Let him yap. I ignored him and walked on. Dogs liked me—or so I thought until the son of a bitch set his teeth around my ankle and broke skin. I kicked him away. It hurt, but the shock was worse. I just stood there as he yapped, a how could you? expression on my face.

I bent over and pulled down my sock. I was bleeding. Not heavily. A steady, ladylike trickle. The defense team would get a kick out of this. If they needed any proof of my dedication, there it was written in red. Not only was I willing to crawl through dust and mud, I would suffer dog bites to try to save Esperanza Morales’s life. I scowled at the mutt through narrowed eyes. He just kept yapping. I pulled back my leg as if I was going to kick him, but he didn’t even flinch.

I realized I had an audience, outside the last house on the right. Another ancient sixty-year-old, her thick legs rooted in the ground like old oaks. Her flesh was a wobbly mass under a striped serape she wore despite the midday heat. Two other women, their middles swollen after multiple pregnancies, in jeans and T-shirts. One sat sifting through a bowl of dried beans, picking out the little stones; the other folded raggedy clothes she picked from a washline. A tiny girl stared. The three adults did not acknowledge the gringo in their midst inspecting his dog bite. I hoped that my victimhood would at least make them sympathetic to my cause.

I limped in a straight line to the old one. If she wasn’t Juventino’s mom, I was Pancho Villa. “Buenas tardes,” I said. “Señora Escobar? My name is Richard.”

She just stared at me. Who the hell was I? How did I know her name?

“Juventino’s mother?” I asked.

She wouldn’t say yes and she wouldn’t say no, not until I showed my cards. She just kept looking at me, her arms folded across her chest.

“Is Juventino around?” I asked. “We have friends in common in los States. I have regards from Esperanza Morales.”

“Let me see if he’s here,” she said, and walked inside.

I turned around and smiled at the other women. They were Juventino’s sisters, or sisters-in-law. One had her eyes on the bowl of beans, while the other’s arm was wrapped around the child. Through enormous brown eyes the kid looked at me as if I were the Werewolf of London. “Hola, guapa,” I said, and waved. She buried her head in her mother’s pubis.

He emerged from the adobe. Short, lean, muscular. A battered Dallas Cowboys cap. A thick black moustache like a hero of the Mexican Revolution, a three-day growth of beard. Watery black eyes. A gray T-shirt with multiple holes—who knows what color it had been when new? An emblem of the Virgin of Guadalupe around his neck. He nodded. I told him to call me Richard and shook his hand. “I’m here on behalf of Esperanza Morales,” I said. “Could we please talk for a few minutes?”

“Sure,” he said.

We were standing on the dirt path to his house. “Thanks,” I said. “Where can we talk?”

“Here.”

I looked down at my ankle. The blood was saturating the dirt and mud on my sneaker. “Could we sit down somewhere?” I said, adding, “I got bit by one of those dogs down the street. I’m bleeding.”

Juventino looked around. “You can sit there,” he said, indicating a pile of rocks with his chin. I could have stayed in Ojeras for ten years and he never would have invited me inside. I squatted on the rocks and removed a stenographer’s notebook from my backpack, a pen from my pocket. Juventino stood over me like Zeus.

“You know that Esperanza’s in jail, right?” I asked.

He paused before answering, as if it had been a trick question. “I think I heard something about that.”

“She’s in jail for murder in Louisiana, in el gabacho,” I said. “The prosecutor wants to give her the death penalty, Juventino.”

“Ooff,” he said, pointing his chin and making an ambiguous moue. He might have felt sorry for her, or he may have been impressed with her achievement.

What I had said about the death penalty simplified the story. She was charged with capital murder for killing a baby, which made her eligible for death. The prosecution had stated that they might seek the maximum penalty, but they always say that when the victim is less than seven years old. They could change their minds up to the last minute, even during the trial, even while the jury deliberated. Until the district attorney made up his mind to go for broke or to accept a plea bargain for a lesser charge, the state had to pay for my investigation.

I let the idea of the death penalty sink in for a minute, before saying, “I work for her lawyer. I’m an investigator. My job is to put together the story of her life, to show the prosecutor that she’s a human being who deserves mercy. Who doesn’t deserve to die.” I spoke slowly and as