ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

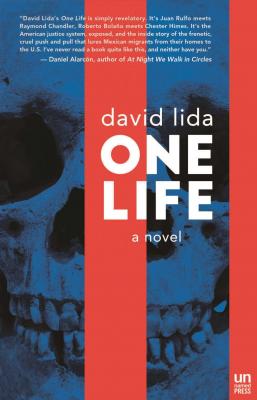

One Life. David Lida

Читать онлайн.Название One Life

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781944700249

Автор произведения David Lida

Жанр Триллеры

Издательство Ingram

“A long time ago.”

“Okay, but, like, how long?” No response. “A year ago? Five years ago? More?”

He nodded. “Yes.”

For Mexican villagers, chronology was at best vague. Sometimes you had to let issues of time roll out with the tide. I hoped that Marta would be more specific when I caught up with her in Morelia. “Tell me about her family,” I said.

“They were buena gente,” he said. Good people.

They were always “good people.” Most people who are facing death row come from families in whose bosoms there is systematic abuse, neglect, violence, and poverty to the point of malnutrition. If you hit the jackpot, you’ll get learning disabilities, brain damage, or mental illness as well—that’s good luck because according to the Supreme Court, you’re not supposed to execute someone who is mentally ill. But to hear the witnesses tell it, they were always “good people.”

“Good in what way?” I asked.

“Good people,” he repeated, looking at me quizzically.

“Good how? Good, like hardworking? Good, like generous, like giving away their food and their money to people who needed it more than they did? Good, like petting dogs and cats?”

A list of questions like that is what is known as leading the witness. You are not supposed to do it. You are supposed to stand there through silences so long that you could drive a convoy of trucks through them. You are supposed to wait for them to answer until your hair turns gray and your teeth fall out and an archaeologist discovers your fossil in the desert after the next ice age. In the real world, at least with someone like Juventino, at times you have to give them a menu of answers to choose from.

“They worked very hard,” he said. He removed his cap and scratched his black hair, brushed away from his forehead. “Don Fernando”—that was Esperanza’s father—“he helped me to find work.”

Reading between the lines: Don Fernando might have beat his wife and children with a skillet every Friday night after dinner, he might have stolen from his neighbors, raped his own grandchildren, and, on some Aztec nostalgia trip, cut out the hearts of his contemporaries and eaten them while they still beat four to the bar. But he helped Juventino find work spreading cement or picking beans. So he was “good people.”

“And what about Esperanza? What was she like?”

“Tranquila,” he said.

How I grew to hate that word. Tranquila: Easygoing. Calm. Peaceful. Quiet. Every single Mexican in jail in the United States is, above all, tranquilo, at least according to their relatives and friends, colleagues and classmates, teachers and doctors.

“Tranquila in what way, Juventino?” I asked. Now he looked at me as if I were a moron. How many ways were there to be tranquila? “Tranquila, as in she was quiet and didn’t say very much? Tranquila, like she was easygoing and helped other people? Tranquila, like if there was a difficult situation, she would try to solve the problem?”

Juventino stopped to consider the choices on the menu, and then something happened to his face. His brow relaxed, and the pupils of his eyes acquired a sheen of glaze like that which envelopes a Krispy Kreme doughnut. He gave up; this was too complex for him. I tried to reel him back.

“Remember, Juventino,” I said. “The state of Louisiana wants to kill Esperanza. I’m trying to help save her life.”

I rolled down my sock to get another glimpse of the wound. The teeth marks and the blood and the dirt were starting to look like the preliminary sketch of an abstract painting. I would need to buy a bottle of iodine on the road to Puroaire, maybe even see a doctor. They would be reimbursable expenses. For the moment, I was hoping against hope that the sight of the wound would help Juventino remember some salient detail about Esperanza or her family.

“She didn’t say much,” he said. Then he held up his hands, tilted his head to one side. “At least not to me. But she was good people.”

For the next twenty minutes I tried every which way to get something, anything, out of the poor guy. I asked each question five times with slight variations, offered him every option I could think of. If his answers weighed in at three syllables, it was a miracle. Finally, I couldn’t think of anything else to say. I just looked at him impassively, hoping the mirror of my face might inspire some memory.

He could tell I was unsatisfied. He only shrugged. “¿Qué quieres que te diga?” he said. In this instance, it was only a figure of speech. But I had an answer prepared for him.

“What do I want you to say, Juventino? You really want to know? Then here goes: I want you to tell me a story. And please, make it a horrible one. A tale of poverty and misery, of incest and abuse, of starvation and terror, of family violence so hair-raising and horrifying that anyone who listens to it will have nightmares forever. If you can include mental retardation, we’re off to the races.

“It has to be a tragic Aristotelian narrative that corresponds to the fundamental order of the universe. There has to be a chain of cause and effect that begins the day Esperanza is born into wretchedness and has its inevitable climax at the moment she kills her baby. Which leads inexorably to her arrest, and for a denouement, the demonstration that she has been a saint in jail and is not only no longer a threat to society but a penitent and productive individual.

“You following me, Juventino? Most importantly, make the story devastatingly sad. The grief, the gloom, the desolation have to be so overwhelming that they will bring even the hardest-hearted, most vengeful Louisiana district attorney to tears. It has to be so heartbreaking that, after hearing it, jurors would rather cut their own throats than send her to the gas chamber.”

Of course I didn’t actually say any of that. I realized that Juventino had no story to tell, absolutely nothing to say about Esperanza or her family. Why should he? In half an hour, I tried to force him into what was probably more conversation than he’d had in the previous month. I asked him to reflect on things to which he’d never given a second’s thought, things that had nothing to do with his existence or survival. In Ojeras, Juventino plants and harvests corn and beans in season, and during the intervals between farmwork, he tries to lay a little cement or hang drywall. That is, if he’s not in California, Ohio, or North Carolina, hiding in the shadows while scrounging for any employment that will give him a little money to send home to his mother and sisters.

“Juventino,” I said, “when I go home, I prepare memos for the lawyers about every conversation I’ve had with each person. I’m seeing a lot of people, and sometimes I realize I have forgotten something important. If that happens, would it be okay if I called you?”

“Sure,” he said.

“What’s your phone number?”

We listened to the birds warble in the trees for a while. Finally, he said, “I don’t have a phone.”

“You don’t have a phone at home?” He shook his head. “A cell phone?”

“No.”

“Okay,” I said. “What’s your address?”

He pointed to the adobe house. “I live there.”

I nodded. “What’s the name of this street?”

Another long pause. “Mamá!” he called. “What’s the name of the street where we live?”

The wobbly lady in the serape shrugged her shoulders. That they did not know the name of their street is not as insane as it sounds. In towns like Ojeras, people tend to identify addresses not by names or numbers, but with a little travelogue: “It’s down by the bakery,” or “It’s up where Lula’s grandmother lives,” or “It’s next