ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

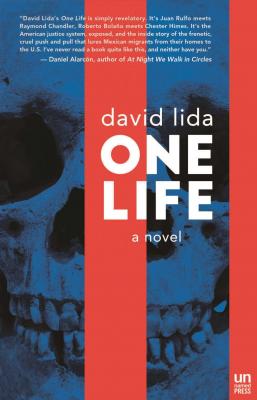

One Life. David Lida

Читать онлайн.Название One Life

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781944700249

Автор произведения David Lida

Жанр Триллеры

Издательство Ingram

M-I-C-K-E-Y M-O-U-S-E

Piecework

Dinner party

Go Greyhound

Back at the ranch

Land of dreams

Lean on me

Home remedies

I’ll fly away

It’s the real thing

It is what it is

Happy hour in the homicide capital of the world

Let’s make a deal

Habeas Corpus Petition

The Defense Rests

May It Please the Court

Acknowledgments

About the Author

I thought of death constantly, but rarely imagined how I would die. Pressed to conjure a vision, an optimistic picture emerged: I’d be one of those lucky slender guys who quietly sneaks into old age in a T-shirt, with thinning silver hair and respectable muscle tone. Not as vigorous as in youth, but without any serious debilitating conditions. You know the type. The guy you see in Starbucks wearing half-frame glasses doing the crossword puzzle, or enjoying the spring sun on a park bench—one of those guys younger men admire, and about whom women remark, “He looks great for his age.” A man who whistles past the boneyard until checkout time, which comes instantly and unexpectedly of a heart attack or a stroke. If it happened from seventy onward, I would have been more than satisfied. Who needs to live any longer than that?

It never entered my mind that at forty-two I would die suddenly and unexpectedly while passing through a dicey no-man’s-land between where I’d been born and the home I’d made. It’s true that dying that way was congruent to the life I had been leading. Some people thought I was reckless because I had never been afraid of Mexico City, and never frightened of the two-donkey towns to which I traveled, where the previous day they had kidnapped the police chief, or a week earlier six people died in a score-settling shootout on the dusty outskirts, or a dozen headless bodies were found in a mass grave. Where at any moment convoys of skinny soldiers swimming in their uniforms, their faces covered with ski masks, balancing Kalashnikovs against their shoulders, patrolled the unpaved streets. All of that was a problem, but none of it was my problem. I thought I lived in a protected bubble because of the work I’d taken on, trying to help save people’s lives.

Not that I was some kind of devil-may-care macho who purported to be fearless. Travels through México profundo came under the realm of acceptable risks. Other things petrified me. I was dreadfully afraid of contracting a hideous illness, like the ones that had killed both my parents. If I got sick, who would take care of me? After my divorce, I had no wife, no children, no mother or father, brothers or sisters. The thought of dying alone unsettled me, but I was scared shitless when I imagined an extended period of sickness and pain with no one around to alleviate my suffering.

It happened in a karaoke bar in a strip mall in Ciudad Juárez. I had been listening to a poor devil—a stocky guy with a Fu Manchu moustache—warble “A Mi Manera,” the Spanish-language version of the song “My Way,” off-key. (What a way to go, right?) Contrary to the cliché, before I died, my life didn’t flash before my eyes. Not precisely. A few Polaroids and postcards crossed my mind. The first snapshots were pornographic; I won’t bore you with the details. Let’s just say that while alive I thought of sex constantly, so it wasn’t strange that it occurred to me as the life left my body. Occasionally I had imagined a happy death while making love. That I didn’t come close to dying that way was just one of life’s malicious curveballs.

I remembered a middle-aged woman with dyed red hair, singing a song called “Gema” as she prepared her stall in a Mexican market early one morning. An old man in a white straw cap, snoozing in a pew in a seventeenth-century church. Sneaking a can of Coca-Cola into a jail in my backpack. A rangy woman with Mardi Gras beads strung around the brim of her hat, pulling up one of the legs of her cargo pants to reveal a .38 Special inside a concealed-carry holster.

My father on his deathbed at Saint Vincent’s. He wouldn’t let go, despite the pain, the grief, the agony, all those chemicals coursing through his ruined, diminished body. He clutched my hand and opened his mouth wide to scream, yet no sound came out. A silent shriek: my last image of Dad. My mother in a housecoat, slowly killing herself by lighting up one cigarette after another. Feeding the olives from my Martini to Carla, our little secret that she was two months pregnant. After we lost the baby, her absence emanating from a gunmetal-gray cell phone that refused to ring.

The lavender carpet of jacaranda leaves on the sidewalks of Mexico City in springtime. Oranges, freshly cut in half and glistening, in a stall outside the market. An aging black man who sat with me patiently after I burst into tears. The ramshackle church in the middle of the middle of nowhere, the choir singing “I’ll Fly Away.”

Once I realized I was dying, there was wonder: I was oddly content, even relieved. I had liked my life. It had been short but often sweet. I smiled inwardly. Was this what they meant when they said you should beware of what you wish for? I was given a death so quick that there was no time to suffer. Sure, I would have liked to have lived longer. If I had actually made it to seventy years, I probably would have wanted to keep going. When I die, hallelujah, by and by, I’ll fly away. Why couldn’t that have been the last song I heard? “My Way”?

Regrets? I had a few. But most of them were so trifling they didn’t even merit consideration. Still, I cannot say the end was peaceful. The last thing I thought of gnawed at me inside, put my stomach in anguished knots. There was some unfinished business between me and a woman named Esperanza Morales. It was irresponsible to die before I had a chance to save her life.

Where the Devil Lost His Poncho

The first thing Esperanza believes will kill her is the smell. It’s a syrupy medicinal odor of disinfectant that comes from the blue liquid with which the floors are mopped in the morning and again in the afternoon. The smell is so hideous that at first, when she awakens at five A.M. for the prebreakfast body count, it brings bile to her mouth. If there were anything in her stomach, she would vomit. The odor creeps up her nostrils to the backs of her eyeballs, where it causes a wrenching headache for hours. And then she realizes that days have passed since she’s last noticed the aroma. She has become used to it.

The second thing she thinks will kill her is the food: pink slices of gristle that leave a coating like Vaseline on her tongue, between slices of stale packaged white bread, smeared with rancid margarine. That’s what they call a sandwich, with none of the condiments that embellish a torta at home—no mayonnaise, tomatoes, avocado, onions, jalapeños, or refried beans. Something else is served at least once a week, a flat brick covered in red paint with yellow powder on top. It’s cold and flavorless—their version of pizza. And then there’s “meat loaf” in “gravy.” It’s not clear whether there’s any actual meat in it, and it tastes as if it’s been thickened with sawdust. The entire saltshaker has been upturned in the sauce, which coagulates thanks to the same jar of Vaseline as the gristle sandwich. This is served alongside a ladleful of mushy kidney beans from an industrial-size can. None of it is ever hot, even when it’s doled right out of the pot, pan, or oven.

At first Esperanza won’t