ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

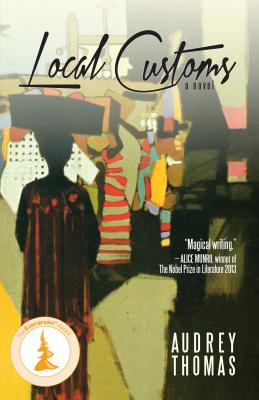

Local Customs. Audrey Thomas

Читать онлайн.Название Local Customs

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781459708006

Автор произведения Audrey Thomas

Жанр Приключения: прочее

Издательство Ingram

No one could be allowed to attack my honour. I could fight a duel or I could marry her. There really wasn’t any choice.

I sent off a letter to Letty, apologizing for the long silence, saying I was still terribly worried about her health in that climate, but that if she was game, then so was I.

Letty

“WHAT WILL YOU DO WITHOUT FRIENDS to talk to?” they said.

“Oh,” I said, “I shall talk to my friends through my books.”

I was about to undertake something new — a series of essays on Sir Walter Scott’s women, beginning with Effie and Jeanie Deans in The Heart of Midlothian. Scott had said their story was based on a true tale, where a young woman was accused of infanticide.

I was also contracted to do some verse illustrations for a new album. I was a dab hand at that sort of thing. If someone handed me an etching of the Fountain of Trevi, I could produce a suitable poem, with just a touch of melancholy, in spite of never having seen the actual thing. Ditto “A Moroccan Maiden” or “A Tuareg and his Camel.”

“Clothed in his robes of brilliant blue —” et cetera, et cetera, et cetera.

I got my wedding without the delights of a wedding. George had said he wanted a quiet ceremony, with no fuss and he preferred we keep our marriage a secret until just before we set sail for the Gold Coast. And so five of us huddled at the front of the church (St. Mary’s, in Bryanston Square) one morning in early June and my brother Whittington did his best to make it a solemn occasion, enunciating every word in his beautiful, deep, clergyman’s voice.

“Do you, Letitia Elizabeth,” “Do you, George Edward,” take this man, take this woman. I was a proper Quakeress in my demure gown of dove grey peau de soie, but George looked splendid in scarlet. I felt like the female bird must feel, eyeing her mate’s more extravagant plumage. The night before I had a crazy vision of William Jerdan rushing in at the last minute, crying, “This wedding must not go forward” and then recounting our shabby past. A somewhat meagre wedding-breakfast followed and I thanked Heaven for Bulwer’s present of some splendid champagne. He made a nice toast, partly in jest, to the “voyage” upon which we were embarking.

George had said he could manage a few days’ honeymoon before he went back to his meetings with the Committee. “Fine,” I replied, “I always maintained that if I were ever to marry I hoped the honeymoon trip would extend no farther than Hyde Park Corner.”

“Oh I think we can stand something a little better than that.”

“Paris?”

In the end we went to Eastbourne, to a hotel which had seen better days. No one would know us in Eastbourne. The landlady, too, was in the initial stages of genteel decay: Mrs. Daisy Harkness, a widow. George liked it — lazy walks along the shingle, tramps up the Downs and down the Downs, damp bedsheets in spite of the stone hot-water bottles. A weekend at Browns’ would have suited me better. Servants with white gloves, starched linen in the dining-room, silver chafing dishes. As I have said, it’s not that I care for breakfast — I rarely partake myself — but the idea of breakfast at a first-class London hotel: that, I like. Coming in with George, my arm tucked into his, the other breakfasters looking up — who is that handsome couple? My goodness, it’s L.E.L. There has been a rumour she was married; so that’s the handsome husband.

My travelling costume, my trousseau, all wasted on the patrons of the Seacliffe Hotel. I could have worn clothes from ten years before. Yet I more and more thought how lucky I was to have found George; it was worth all that tartan material at five shillings a yard and two pairs of good shoes utterly ruined from promenading in the parks and gardens.

We met a dreadful couple at that hotel in Eastbourne. He was some sort of retired officer from Wydah with a thin, sallow wife; he very reddish, she very yellowish; he very stout, she very thin, like Jack Spratt and his wife. They both tied for the first prize in boredom. Will George be like that, when he’s old? I thought. Even more terrifying, will I be like her?

Of course she had to warn me about the “terrible dangers” of life in Africa.

“Do you mean the snakes? The driver ants? The diseases?”

“I mean, Mrs. Maclean, the servants. You can’t trust any of ’em. They’ll slit your throat if they get worked up with palm wine or rum and think you’ve done ’em an injury. Keep everything locked up — everything. Be severe. Threaten flogging.” She leaned even closer. “Don’t ever let them touch you!

“You see, what you will shortly discover is that these creatures have no moral sense, none whatsoever. And as for their customs, their beastliness. Dis-gus-ting,” she said, enunciating every syllable.

“Do you have no happy memories?”

“Ha. Not really. Charles does, many. But it’s different for men. Women have to be always vigilant, always on guard. And should you be—” her voice dropped to a whisper “— violated in your dressing-room while your husband is on trek, do you think other black servants will come to your rescue? Not likely.”

I thanked her for her advice and excused myself. She called after me, “Flannel next to the skin!”

George stayed down for at least another hour.

“Awful old bore,” he said.

“Why, then, did you linger?”

“Oh well, he wanted to talk. I think he misses all the fun.”

“The fun?”

“Yes.”

I was already in bed, under the damp sheets and damp eiderdown.

“Come to bed, George, before I freeze to death.”

He blew out the lamp and whispered, “Dear Letty, I shall be gentle.”

(I had contemplated making a small cut on my wrist and collecting the blood in a tiny vial, so that there would be “proof” of my chastity. I gave up the plan because I didn’t think George was the sort to notice such things.)

There were a few strokings, a few thrusts, a few little whimpers from me, and then we were truly One.

Just before he turned over and fell asleep, he said, “What was the wife going on about?”

“About how much fun it was going to be. In Africa.”

We went back up to London after three days and stayed with friends until we left for the ship. Our marriage had been found out, probably through Bulwer, who could never keep a secret, and I did get some of the attention and presents a bride is entitled to. I hardly saw George; he didn’t even take time off for Queen Victoria’s Coronation procession, but I watched it with great interest, surrounded by friends. We were looking down from a second-storey balcony, to avoid the throngs that lined the streets, so of course we couldn’t see her face as the carriage passed, but I couldn’t help but wonder what her life would be like, every moment of her day regulated according to tradition. Every movement observed; every utterance noted. I didn’t envy her, our first reigning queen since Queen Anne. What is that old proverb? “A favourite has few friends.” In my own, much smaller way, I had discovered how true this was. Detractors, scandal mongers — they buzzed around me like wasps. Indeed, there was a nasty scandal sheet called exactly that, The Wasp.

Would Victoria succeed or fail? She was very young, eighteen, nineteen? And would need good advisers. Even so, how many of those courtiers who bowed to her and fawned over her today, would secretly wish her ill? How well Shakespeare understood all that: “Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown!”

If I had not married George, I would no doubt have lived to what they call a “ripe old age.” But in what circumstances? My popularity was already waning, my commissions for scrapbook verses drying up, and prose becoming