ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

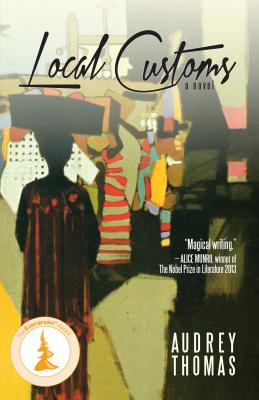

Local Customs. Audrey Thomas

Читать онлайн.Название Local Customs

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781459708006

Автор произведения Audrey Thomas

Жанр Приключения: прочее

Издательство Ingram

“How do you do, brother George,” he said, extending a hand that was none too clean. I took it anyway.

“I’ve been out hunting,” he said.

“And were you successful?”

“Two grouse, which I’ve left in the larder. I didn’t take the old dogs,” he explained, “but went alone. They make too much noise. I really need a young dog, Father, and I’ve seen some nice pups in the town.”

“And who will take care of the young dog when you set out on your adventures?”

He smiled at us. I could see what a charmer he was.

“Perhaps he will come with me.”

“A variation of Dick Whittington and his cat, perhaps?”

I had a sister who died at twenty-one and my two remaining sisters had married. One was in Elgin and the other in Edinburgh; I had nieces and a nephew I’d never seen. I wondered if James was lonely at all, but it turned out that he, too, had been at Elgin Academy and his final term would start in a few days.

I soon fell into a pleasant routine and tried to forget about Letty; I knew I would have to get out of this engagement, but I wasn’t quite sure how to do so. For the first few weeks I deliberately ignored the letters she sent, said nothing to my family (I knew my father would wait for me to speak), and spent most of my daylight hours out of doors.

Letty

WHEN HE WAS VERY ILL just after we landed, he called out a name in his delirium, at least I thought it was a name. “George,” I said, “you were calling out last night and the night before: ‘Ekosua! Ekosua!’ What does that mean? Is Ekosua a name?”

“No, not at all. It’s a local curse word.”

I didn’t believe him so I asked Brodie. “Is Ekosua a name?”

“Why do you ask?” He looked quite uncomfortable.

“Oh, I don’t know. I’ve heard it, more than once; I wasn’t quite sure whether it was a name or a command, or what.”

“It’s a name, a female name. If you were born on a Monday then one of your names will be Ekosua. A boy would be Quashie.”

“Hmmm. So did Robinson Crusoe call his Negro servant Friday because that was the day of the week on which he was discovered, or did Friday tell him his name was ‘Friday’?”

“He would have said ‘Kofi’ or some variant of Kofi, if the island was near Africa, but I don’t think it was.”

“I have a copy with me; I’ll look it up. It was my favourite book when I was a child.”

“And mine as well.”

And so we chatted on and I diverted him from my enquiry about the name Ekosua. George’s country wife, Ekosua — Monday’s child.

Weeks went by and he didn’t answer my letters. Sometimes I felt as though I had conjured him up and then “poof,” my phantom lover disappeared. I wrote and wrote to him, nearly every day now. George was a gentleman and a gentleman did not behave in this fashion. (A little voice said “Letty, you let him get away.”) Finally I wrote to Whittington. I was terrified the scandalous rumours about me had reached George even up there in the Highlands. No one knew, of course, about our engagement, so there would be no public humiliation, but I would know and that knowledge would kill me. I confided in my closest friend, I had to. I told her I would kill myself if this marriage didn’t come off and I meant it. I knew Maria would tell someone in confidence who would tell someone else in confidence and so it would travel through London. Another broken engagement. “Poor Letty,” said with a smile and a simper. “Or maybe she made the whole thing up?”

George

IT WAS WRONG OF ME TO KEEP SILENT FOR SO LONG, BUT I DIDN’T know what to do. Finally I asked my father and Elisabeth for advice. The whole sorry tale came tumbling out, how it must have been a coup de foudre, how I was an absolute nincompoop when it came to women, how she was the last person I should take out to the Coast; she’d be dead within a month.

“Have you told her that?”

“Not in such harsh words, but yes. The men die like flies, and I understand from a letter from William Topp, who is acting president while I’m away, that of the first group of missionaries who arrived in January, only one remains. The missionaries who already resided there were dead before the others stepped on shore.”

“But you knew about the climate when you asked her to marry you.”

“I did, I did. And I told her about the snakes and the poison berries, everything I could think of.”

“And what did she say?”

“She said, ‘You can’t scare me.’ This is a woman who lives life in her head; she has no idea … In fact, I think she finds all this ‘exotic.’”

I put my head in my hands. “What am I to do?”

Elisabeth said softly, “Do you love this woman, George?”

“I thought perhaps I did. Maybe I was simply in love with the idea of having an intelligent companion … out there.”

“Does she love you?”

“In her own way, I suppose. We haven’t used the word ‘love’ very much.”

“Well,” said my father, “you must make your own decision. The lady herself has given you an out. She sent you up here to ‘think it over,’ before the engagement was made public. You seem to have thought it over and you do not wish to marry.”

I could not bear to tell them that her latest letter threatened suicide. I was not a man who took kindly to threats. I told myself that she was merely hysterical — and justly so, considering my long silence — but suppose she meant it? What then? How could I live with myself?

The day after my talk with my parents, I determined to take a long walk to clear my head and then, that evening, to write to Letty and to tell her in the kindest way possible, that the engagement was off. “My dear sweet Letitia,” I would begin, “There is no nice way of saying this …”

I hiked to Lossiemouth, taking some bread and cheese and a flask of tea with me, and ate my simple meal leaning against a rock and staring out over the soft brown sand at the ocean beyond. The fishermen here were a hardy lot, but their wives were even hardier, hiking up their skirts and carrying their husbands on their backs, out to the boats, so that their garments would not be wet when they set out on those chill waters. When the men returned with the catch, it was these same women who filleted the fish and smoked them and packed them for transport south. All this as well as their ordinary household duties — meals, children, washing, and so on. They might have been ignorant of anything except their own rather narrow world, but even as a boy I admired them (although their children ran after me hurling stones and insults). What a contrast between these women, with their huge, competent hands and wind-scoured cheeks and the hot-house bloom I had asked to marry me. Strange to think that what I was staring at as I ate the last crumbs of cheese was that same ocean I look out on from Cape Coast Castle. So cold here it could drown a man, in wintertime, in a matter of minutes; so warm over there, it felt like soup.

“My dear sweet Letitia,” I practised, “I admire you so much, but I cannot find it I my heart to marry you.”

“Dear Letty, you told me to go away and think about our engagement, to be ‘absolutely sure’ — those were your words — that we were right for one another—”

“Dear Miss Landon …” No, too cold and uncaring.

I sat there most of the afternoon, dreading what was to come, cursing myself for ever getting