ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

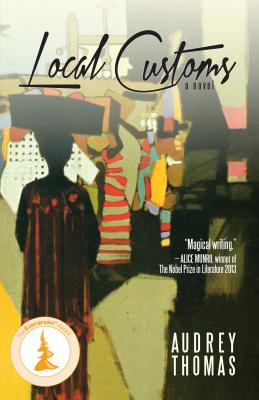

Local Customs. Audrey Thomas

Читать онлайн.Название Local Customs

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781459708006

Автор произведения Audrey Thomas

Жанр Приключения: прочее

Издательство Ingram

When I wrote to my mother to tell her that George and I were married (“Captain George Maclean, governor of Cape Coast Castle on the Guinea Coast, a fine man from a good family”) she replied almost at once to say she supposed that would be the end of her subsidy. I was so angry that I almost cut her off, but in the end I couldn’t do it. I never felt that Whittington or my mother were aware of how hard I worked to provide them with their extra money. I never felt any real gratitude from either of them. I suspect, like the rest of the world, they thought I just “tossed off” a poem here or a novel there in between going to dinner parties and soirées. Even some of my so-called friends said, “You’re so prolific, Letty,” and I was, but writing is drudgery, writing is hard work. There were times when my hand seized up with cramp and had to be massaged with creams before I could take up my pen again, and there were nights when my back ached and my head ached and my eyes felt full of grit. And always there was my old trouble, which sometimes kept me in bed for days at a time.

I had been engaged to a fine man, although he and his crowd denied it later on. I broke it off because of malicious gossip about me and another gentleman.

After that I was so ill I truly thought I was going to die. If it hadn’t been for Dr. Thompson and his ministrations I might have slit my wrists just to stop the agony. It is not that I was born sickly, like my sister; in fact I had a good constitution except for this one thing. My “Achilles heel” if you like, only a little farther up.

(And in the evening I was supposed to change from drudge to dazzler, call for the maid to help me with my hair and fastenings. Ellen was a maid-of-all-work, as well as cook, but all-work did not include helping me with my toilette. I was maid as well as Mademoiselle, who struggled with buttons and bows, then pinched my cheeks to make them glow.)

George

I DIDN’T WOO HER; if anything, it was the other way around. Although Africa came into it — oh yes — and the uniform. If I had been a gentleman farmer or a man of business (a man of non-literary business; publishers were a separate breed) I doubt if she would have given me a second look. In her eyes I was a romantic figure. Damned Forster had given her that Apollonia report before she even met me; it was almost as though she conjured me up from that, a different George Maclean from who I really was. Not that I ever pretended to her, never that.

What was I thinking of? She was the last person I should have married — a city woman with city tastes. How on earth would she manage at Cape Coast? And yet, as we walked along together and she took my arm, I felt comforted by her presence. How long had it been since a woman had taken my arm, had pressed my hand, had said, “Tell me all about yourself.” You don’t think you’re lonely out there — or you try to convince yourself that you’re not. But you drink too much or you take a country wife, but that only helps with the carnal side of one’s nature. Even if you speak the language well (which I did) you can’t discuss ideas with such a woman. It’s not that I wasn’t grateful to Ekosua — she was a wonderful nurse when I was ill, bathing my face with lime juice and water, forcing me to drink some horrible concoction which almost instantly brought relief. And the carnal side — well, that was good too. Young girls mature early out there and I’ve been told that the old women, at the appropriate time, take them aside and teach them how to please a man. Can you imagine such a thing happening in England?

I was sorry to send her away — Ekosua — but I knew she would understand. I made sure she was given a generous gift of money. William Topp took care of it for me — or at least I hoped he had. I left the ship in the middle of the night, and went in by canoe just to make sure. I told Letty the next day that I had wanted our apartments fumigated with charcoal and thoroughly swept before she set foot in the Castle. I don’t think she believed me, but she said nothing. (She knew about my “wife” out here — rumours had reached England — but she seemed satisfied when I said that had been over long ago. Not quite the truth, but a necessary half-truth, for the sake of peace.)

Letty wore just a hint of some eau de cologne she had brought back from a holiday in Paris; she used it sparingly but it was always there and when I at last set off for Scotland in the new year she gave me a small handkerchief dabbed with cologne, “to remind you always of your admirer who awaits your return.” I regret to say I left it at the hotel.

Once up at Urquhart I honestly wondered if I hadn’t been bewitched by her, her white hands, her dainty feet, her silky hair, the way she said my name — “George,” in such an intimate way. It is hard to explain, but to a chap who has spent most of his adult life looking at half-naked women, however lovely (and the young women are truly beautiful), there is something exciting about a woman fully clothed. One can’t help thinking about what’s underneath all those skirts and petticoats. And the women know it; hence the décolletage, if that is the right word, the glimpse of plump shoulders or an ivory neck.

(There were rumours about Letty, hints of a scandal, but I firmly dismissed all this as just talk, envious talk, because she was admired and successful. In any event, I was in no position to cast stones.)

The farther north I travelled, the better I could breathe, and once I left Edinburgh, only stopping for a few hours, I lowered the window on the coach, much to the objections of a stern, black-clad couple, who were my only companions for the rest of the journey — or as far as Aberdeen. They shrank from the fresh air as though it were a poisonous effluvia.

“Just for a moment,” I said, with my best smile. “I haven’t been home in so long.”

If you have never smelled the Highland air, I don’t know how to describe it to you. If you have spent your entire life in cities, you might be horrified when I said it smelled of coolness, of heather and peat, of the earth and simple things. (Letty’s handkerchief had no place there.) I gulped it, head hanging out, like a schoolboy or a dog.

“If you please, Sir,” said the stern, black-clad gentleman.

The dogs recognized me first and set up quite a din. Dusk was falling fast, but there was my father at the door of the manse, holding up a lantern.

“George. You’ve come at last.”

I wondered if I was as much a shock to him as he was to me. How could he have aged so quickly since my last visit — his hair a white cloud around his head, his hands that clasped mine so thin. But his smile was just as warm and the fire burned just as brightly in the parlour. He banished the dogs to the kitchen, where they whined and scratched at the door until he relented — “just this once, mind,” he said, although somehow I doubted it was “just this once.” The smell of them almost made me weep.

My mother died when I was fourteen and shortly thereafter I joined the army. Since then, I had only been back for short intervals and I did not grow up at Urquhart, but in Keith and then, as a schoolboy, in Elgin, where I boarded with the Latin master. So Urquhart wasn’t really “home,” in any historical sense, but Scotland was home and my father was home and a Scottish manse is a Scottish manse; this one had the same air of cheerful frugality as the one where I had spent my earliest years. A little bigger, maybe, with a nice glebe surrounding it, but much the same.

My mother’s name was Elisabeth and my father had remarried another Elisabeth; it was easy to see that the marriage suited them both. I noticed right away the glances she gave him. Once, after returning to the room with the tea tray (“We’ll just have a wee cup the noo, to take the chill off you and supper later.”) She set everything down on a low table, then stood up again, and touched him lightly on the shoulder. His hand went up and clasped hers. Would Letty and I have anything like this?

My brother Hugh was a surgeon with the Indian Army, due home on leave in ’38 and my other brother, John, my confidante, the brother I felt closest to, was dead; but my father and stepmother had a son, my half-brother James, who came crashing