ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

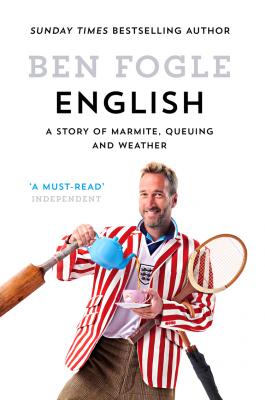

English: A Story of Marmite, Queuing and Weather. Ben Fogle

Читать онлайн.Название English: A Story of Marmite, Queuing and Weather

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780008222260

Автор произведения Ben Fogle

Жанр Юмор: прочее

Издательство HarperCollins

‘What am I going to talk to her about?’ I worried as I made my way to Windsor. There were so many things I could tell her, about the places I had been and the adventures I had experienced. I would tell her about Antarctica, and of the time I met a tribe in the jungles of Papua New Guinea. Perhaps I would recall meeting the Prince Philip Island cult, or the time I met some of her Labradors.

‘It’s terribly cold, Ma’am, isn’t it?’ I smiled as I shook her gloved hand.

‘Warmer than last December. Though we could do with a little rain,’ she replied.

We both nodded, and she headed off to chat to the next guest.

And that just about sums it up. My first opportunity to chat to Her Majesty, and I talked about the weather.

I have found myself in the most unlikely situations around the world discussing the nuances of the English weather. And here’s the thing: we don’t really have weather. As Lucy Verasamy told me, it can be a little rainy, a little windy, sometimes a bit sunny – but let’s be honest, the strangest thing about the English weather is that it’s all a little meh. Compared to other countries it really is quite benign.

If you doubt me here, just take a trip to the Andes, or Borneo or even the US, and you will see what I mean by BIG weather. I’m talking about hurricanes, tornadoes, freezes, heatwaves. In England we have variables, but most of our weather-related conversations revolve around too much rain, or too little rain, or it being too warm, or too cold. And that is about it. It amazes me that we are capable of talking about the weather so fluidly and constantly when it varies so little.

Visitors from abroad are thoroughly bemused by the English fixation with the weather – because the only extreme aspect of our weather is its changeability. The conditions our climate might usher in from one day to the next induce inordinate anxiety, even though we technically ‘enjoy’ a temperate climate, with temperatures rarely falling lower than 0°C in winter or rising higher than 32°C in summer. English weather plays out its repertoire of conditions right in the middle of the range of potential hazards – certainly without the blizzards, tornadoes, hurricanes, killer heatwaves and monsoons that plague other geographical zones. We don’t have to batten down storm hatches, switch to snow tyres or build homes to strict storm mitigation codes (as they do in New England). We don’t have companies offering storm-chasing adventure holidays. It is said that, on average, an English citizen will experience three major weather events in their lifetime. The singular characteristic of the English weather is that it changes frequently and unexpectedly.

And this leads on to another point about our relationship with our weather: our propensity to complain about it. This is at odds with the Blitz-like spirit of ‘mustn’t grumble’, but we do. I think we have a tendency to be a pessimistic nation, particularly when it comes to the weather. Is there such a thing as ideal weather for the English? Isn’t it always too hot or too cold, a bit grey or intolerably windy, unbearably humid or relentlessly drizzly? It’s rarely right.

How many times have you heard someone saying the weather is perfect? Even on those rare cloudless, windless summer days of unbroken blue sky, there is often some reason to lament the weather: ‘It’s too hot’, ‘The grass is turning brown’, ‘We need rain’, ‘Careful or you’ll get sunburn’. You get the point.

But somehow the weather is part of our psyche. It may have something to do with our geographical location in the North Atlantic and the resulting propensity for it to rain.

Here are some English weather stats. The hottest recorded temperature was 38.5°C (101.3°F) in Faversham in Kent on 10 August 2003. The hottest month in England is August, which is usually 2°C hotter than July and 3°C hotter than September. The sunniest month was over 100 years ago, when 383.9 hours (the equivalent of thirty-two 12-hour days) of sunshine were recorded in Eastbourne, Sussex in July 1911. The lowest August temperature was minus 2°C on 28 August 1977 in Moor House, Cumbria. Highest rainfall in 24 hours was 10.98in (279mm) on 18 July 1955 in Martinstown, Dorset. The largest amount of rain in just one hour was 3.62in (92mm) in Maidenhead in Berkshire on 12 July 1901. The lowest temperature recorded in England was minus 26.1°C at Newport in Shropshire on 10 January 1982.

Wherever I am in the world, I am asked about the weather at home. I never know whether this is genuine curiosity about the renowned unpredictability of English weather or a reliable conversational gambit – an ice breaker, so to speak – because it is assumed that anyone hailing from England is totally fixated on the weather. As Professor Higgins told Eliza Doolittle when he launched her into society in the film My Fair Lady, it is advisable when making conversation to ‘stick to the weather and everybody’s health’.

It’s true that the English always hope for a White Christmas or a Summer Scorcher, and worry about a Bank Holiday Wash-Out or a Big Freeze. Weather warrants capital letters. It has status in everyday life. But the obsession is not just with the big picture; it is about the minutiae of each day’s conditions. There is no doubt that the English are genetically tuned to be on tenterhooks as to (a) what the weather is looking like each morning and (b) whether conditions are exactly as have been forecast.

We secretly like the fact that our weather continually takes us by surprise, often several times in the course of one day. The changeability of the weather has been a source of marvel, anxiety and unfailing interest since the year dot. In 1758 Samuel Johnson wrote an entire essay entitled ‘Discourses on the Weather’. ‘It is commonly observed,’ he pointed out, ‘that when two Englishmen meet, their first talk is of the weather; they are in haste to tell each other, what each must already know, that it is hot or cold, bright or cloudy, windy or calm …’ He went on to explain that

An Englishman’s notice of the weather is the natural consequence of changeable skies and uncertain seasons. In many parts of the world, wet weather and dry are regularly expected at certain periods; but in our island, every man goes to sleep, unable to guess whether he shall behold in the morning a bright or cloudy atmosphere, whether his rest shall be lulled by a shower or broken by tempest.

So, long before our national addiction to social-media alerts, breaking newsflashes and live online updates, the English had the weather to spice up conversation on an almost minute-by-minute basis.

Enter a particularly English social stereotype: the weather obsessive. An article in Country Life in 29 August 2012 surveyed the type, which has existed since medieval times. ‘Who, from the hotly contended field, takes the Golden Barometer as Britain’s most possessed weather obsessive?’ asked Antony Woodward.

Would it be William Merle, the so-called Father of Meteorology, who had the curious idea of keeping a daily weather journal in 1277, persisting doggedly for 67 years? Or William Murphy Esq, MNS (Member of No Society), Cork scientist and author of little repute, whose 1840 Weather Almanac (on scientific principles, showing the state of the weather for every day of the year), despite correctly predicting the weather for only one day, became a bestseller?

How about Thomas Stevenson, one of ‘the Lighthouse Stevensons’, who measured the force of an ocean wave with his ‘wave dynamometer’ before going on to devise the Stevenson Screen weather station? Admiral Beaufort, perhaps, whose eponymous wind scale sailors still use? Or the artist John Constable, whose ‘skying’ cloud paintings ushered in a new scientific approach to the depiction of the heavens? Dr George Merryweather, inventor, is surely a contender for his 12-leech ‘tempest prognosticator’. Then there’s poor Group Capt J. M. Stagg, on whose knotted shoulders rested the decision of whether to go, or not to go, on D Day. Or perhaps it’s the humble Mr Grisenthwaite, who’s assiduously kept a two-decade lawn-mowing diary (and why not?) that was, in 2005, accepted by the Royal Meteorological Society as documentary evidence of climate change?

In all honesty, I’m surprised that there aren’t more examples of English people obsessed with our weather.

And the funny thing is, we still look to the weather for daily interest – even more