ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

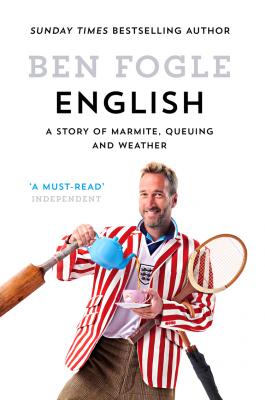

English: A Story of Marmite, Queuing and Weather. Ben Fogle

Читать онлайн.Название English: A Story of Marmite, Queuing and Weather

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780008222260

Автор произведения Ben Fogle

Жанр Юмор: прочее

Издательство HarperCollins

‘Apologizing. We are always apologizing,’ stated another woman to a chorus of agreement.

‘Roses and gardens.’

‘Tea.’ This got the loudest endorsement.

‘Baking and cakes.’

‘The Queen.’

I asked them whether they would ever fly the St George’s Cross from their homes. There was an audible gasp, accompanied by a collective shaking of heads.

‘Why not?’ I wondered.

‘Because it has been hijacked by the extreme right,’ answered one woman.

‘It represents racism and xenophobia,’ added another.

‘We aren’t allowed to be English, we are British.’

I asked whether we should celebrate our national identity more like the Welsh, Scots and Northern Irish. To which the whole room nodded in approval, not in a jingoistic, nationalist kind of way, but in an understated, English kind of way. It was a genteel, considered discussion of the virtues of Englishness and the erosion of our national patriotism.

‘The Last Night of the Proms is as patriotic as we get,’ explained another member of the group, ‘but that patriotism is about the Union.’

Here England was speaking. We have a solid idea of what it is to be English, we have a grasp of some of the character traits of living Englishly, but we no longer celebrate that Englishness.

I asked if it was time to reclaim our national identity and take pride in being English. There was a round of applause.

‘Reclaim the celebration of Englishness for us, Ben.’

And that is what this book is about.

LIVING ENGLISHLY

I am standing at the top of a vertiginous hill. When I say vertiginous, I mean the gradient is 1:1 in places, so steep you can’t stand up. A damp mizzle has descended on the valley, coating the grass in a greasy layer of moisture that has in turn soaked into the soil, turning it into an oily runway of mud.

It is the kind of mizzle that soaks you unknowingly. It has a stealthy ability to drench clothes, hair and skin before you have even noticed. Large drips of rain begin to fall from the peak of my flat cap, worn in a hopeless attempt to keep a low profile. My heart leaps and my stomach lurches as I take in the contours of the steep hill.

On this Spring Bank Holiday Monday, hundreds of people are streaming across the fields below, yomping along the narrow footpaths that bisect the fields. Next to me a German from Hamburg is busy fitting a mouth guard to his teeth, while a New Zealand rugby player is shoving shin pads down his long socks.

Along the brow of the hill, flagged by a simple plastic fence, are a further dozen nervous-looking faces from across the globe who have descended on this damp Gloucestershire hill for arguably one of the most famous eccentric sporting events in the world, the annual Cooper’s Hill Cheese Rolling. To paraphrase one social commentator, it involves ‘twenty young men chasing a cheese off a cliff and tumbling 200 yards to the bottom, where they are scraped up by paramedics and packed off to hospital’.

Which is about right. The steepness of the hill, combined with the undulations and the enthusiastic adrenalin of young men being cheered on by a crowd of thousands of spectators, leads to broken legs, arms, necks, ribs and even backs as a handful of brave souls chase a 9lb Double Gloucester cheese downhill at 70mph.

Why they started doing it, nobody really knows, although there are theories. The most colourful is that it has pagan origins. The start of the new year (spring) was celebrated by rolling burning brushwood down hills to represent rebirth and to encourage a good harvest. To enhance this the Master of Ceremonies also scattered buns, biscuits and sweets at the top of the hill. Cheese rolling is said to have developed from these rituals, although the earliest record of it dates back only to 1826.

During rationing during and after the Second World War a wooden cheese was used, with a small triangle of actual cheese inserted into a notch in the wood. In 1993, fifteen people were injured, four seriously, and in 2011, a crisis hit when the cheese rolling was cancelled after the local council decided to try to impose some order on this typically ramshackle English event. The council stipulated that the organizers should provide security, perimeter fencing to allow crowd control and spectator areas that would charge an entrance fee. The official competition was cancelled and the event went underground … which meant it continued as normal, but without any official organization, and with no ambulances.

Since then, the event has continued to grow, courtesy of a clandestine group of anonymous ‘organizers’, their identities shrouded in secrecy to avoid prosecution. Cooper’s Hill Cheese Rolling continues to attract thousands of spectators and dozens of competitors from all over the world.

And now I find myself on the top of the famous hill next to an assortment of adrenalin junkies, waiting to take part myself.

‘You gonna do it?’ smiles a young lad holding a beer.

‘Maybe,’ I shrug. ‘You?’

‘No way mate, I’m not mad,’ he smiles.

A couple of local men with a semi-official air and wearing white coats are milling around.

‘Are you an organizer?’ I ask a man busy organizing.

‘Nah,’ he replies with a smile, ‘no organizers here.’

Another man in a white coat is busy with a bag of cheeses, a slight giveaway as to his official status. ‘Are you an organizer?’ I ask.

‘No, mate,’ he replies as he unpacks the cheese.

‘You’re not going to race the cheese, are you?’ asks an athletic-looking woman.

I shrug my shoulders.

‘Well, I’m the only medic here,’ she replies with a slight look of concern.

Hundreds and thousands of people continue to envelop the hill, which is now thronging with people of all ages, here to witness the unofficial official cheese-rolling championships. It seems incredible that the event has seemingly been so well organized when there are no official organizers. Without structure, money or a committee, the event has somehow managed to corral spectators, crowd control and competitors. It is perhaps a fine reflection of Englishness that the entire event is so beautifully managed.

Back to the top of the hill and my heart is pounding as I wait for the count to begin, images of broken bones racing through my mind.

‘I broke my neck racing the cheese last year,’ smiles a young girl. ‘I can’t decide whether to race it again this year,’ she adds.

‘I’ll count to four,’ instructs the official-looking unofficial. ‘We will release the cheese on three, you run on four.’

I look around at the nervous faces beside me as people dig their heels into the slippery slope. The hill is so steep and the mud so ice-like that it is difficult not to let gravity take its course even while sitting. Every so often one of the competitors slides a couple of metres down the slope, before struggling back up.

Next to me is Chris, the multi-winning champion who is also a serving soldier. ‘Any secrets or advice?’ I ask nervously.

‘Just go for it. Commit to the cheese,’ he smiles, ‘and keep the body loose.’

So worried have the army been about his participation and likely injury that they urged him not to compete, even changing his shift to coincide with the morning of the event. But wild dogs wouldn’t keep Chris from competing in his beloved event. He is the joint world champion cheese-roller, winning two cheeses – an honour he carries with pride.