ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

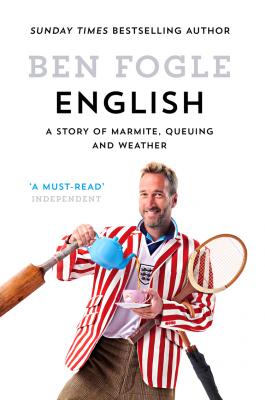

English: A Story of Marmite, Queuing and Weather. Ben Fogle

Читать онлайн.Название English: A Story of Marmite, Queuing and Weather

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780008222260

Автор произведения Ben Fogle

Жанр Юмор: прочее

Издательство HarperCollins

Eccentricity aside, I consider myself a proud Englishman. I was born in Marylebone, London, the capital of England. I am a Land Rover-driving, Labrador-owning, Marmite-eating, tea-drinking, wax-jacketed, Queen-loving Englishman. And yet technically I’m not. I’m actually an imposter. My grandfather was Scottish and my father is Canadian. In all honesty, I am a mongrel. A mixed breed with no obvious authority to write a book about Englishness, And yet I have lived my life being described as the quintessential Englishman. Over time some of those traits and characteristics have perhaps become exaggerated. I blame travel. Despite my childhood adoption of a few Canadian pronunciations, my accent and dialect has changed according to my location. Believe it or not, I haven’t always sounded like this. Like what? you might ask. Well, for those who have never heard me talk, I am a little bit Posh. Correction. I’m not posh but I sound posh. RP – Received Pronunciation – is the official term. IT MEANS I PRO-NOUNCE EVERY WORD AND SYL-A-BYL CLEARLY.

The first changes to my accent came when I went to live in Ecuador, South America. For the first time, I became proud of my heritage. Subconsciously it was probably also an effort to distance myself from America and Americans. I lived with a beautiful family called the Salazars, and Mauro, my Ecuadorian ‘father’, was obsessed with all things English. ‘Tell me about hooligans?’ he would ask over a plate of beans and rice. ‘And what about the Queen?’ He was obsessed with Benny Hill and Oasis and Four Weddings and a Funeral.

He would spend hours quizzing me on the motherland, and I suppose I began subliminally to morph into a sort of Hugh Grant caricature. Several further years in Central and South America and I became fixated on my heritage, hoarding jars of Marmite and boxes of PG Tips. It was only when I returned to give a talk at my former school in Dorset that one of my teachers commented on the changes to my accent.

I genuinely believe that it is all the time away, overseas, exploring and adventuring that has given me time to think and explore my national identity. Sometimes, when you are too close to something, it is difficult to reflect honestly; often, we don’t like what we see.

Let’s be frank: England itself doesn’t have a glowing halo when it comes to colonial and imperial history. Indeed, we are rightly embarrassed by much of our past. And now we face turbulent times in which we, as the wider nation, have been forced to ask ourselves who we are. What began with an emotionally charged independence referendum for Scotland ended with Great Britain’s decision to leave the European Union. In the light of all of that, what does it mean to be English?

It is a loaded subject and a loaded book to write, full of pitfalls and taboo subjects that cause upset and irritation. It is why I occasionally feel I should never have written it. It is the reason I have agonized over it. It has given me sleepless nights.

Of course, it is easy to paint a national character with brushstrokes of stereotyping, and I will make no apology for my effort to explore many of these traits. After I had got beyond the stream of abuse from Scots, Welsh and Northern Irish occasioned by writing a book about Englishness, the character traits people suggested most often on social media were queuing, Marmite, umbrellas, the Queen, tea, fish and chips, Wimbledon, not complaining, bad teeth, dry humour, wax jackets, muddy Glastonbury, politeness, and the weather.

All of them iconically English, but it is the weather that has fascinated me the most. It is such a huge part of our national identity. It dominates our conversations. It is the subject of endless fascination and has, in my humble opinion, been the catalyst for so much of what makes England and the English what we are.

Again, if I’m honest I wanted to write a book about the weather. I wanted to explore our complex relationship with the weather – something we love to hate. The more I explored and researched, the more I became convinced that it is indeed the weather that has come to define us as a nation. Almost everything, every national trait and quirk and foible, can be attributed in some form to the weather. Okay, sometimes the link can be pretty tenuous, but it’s always there. So, often in this book, the chapters will explore a topic and our climate will be lurking in the background, lighting the subject with its changeable, unpredictable presence.

When I was a young boy, there was a song that we used to play over and over. It was one of my mother’s songs from the film Half a Sixpence, in which she starred alongside Tommy Steele. I can still remember every word:

If the rain’s got to fall, let it fall on Wednesday,

Tuesday, Monday, any day but Sunday

Sunday’s the day when it’s got to be fine,

’Cause that’s when I’m meeting my girl.

If the rain’s got to fall, let it fall on Maidstone,

Kingston, Oakstone, anywhere but Folkestone,

Folkestone’s the place where it’s got to be fine.

’Cause that’s where I’m meeting my girl.

What could be wetter or damper

Than to sit on a picnic hamper

Sippin’ a sasparella underneath a leaky umbrella?

If the rain’s got to fall, let it fall on Thursday,

Saturday, Friday, any day but my day.

Sunday’s the day when it’s got to be fine,

’Cause that’s when I’m meeting my girl.

The weather is a fundamental part of who we are. It has been estimated that weather-obsessed British people spend on average six months of their lives talking about whether it’s going to rain or shine, according to a survey published recently. Speculation about whether it’s going to be wet, complaints about the cold and murmurings about the heat are also the first points of conversation with strangers or colleagues for 58 per cent of Britons, the survey recorded. Another study found that Britons talk about the weather for about two days (forty-nine hours, to be exact) every year and the subject comes up more often than work, what is on television, sport or gossip.

Nineteen per cent of over-65s questioned also believe they can predict the weather as well as a professional weatherman. We are a nation whose starting and ending points are the weather.

The more I roamed England, the more I turned the nature of the book over in my head. Then one day, as I walked through the rain along Blackpool beach, I thought to myself, ‘That’s it. This is an honest portrait of my own experiences of Englishness over the years. The weather seeps into every corner of our English personality but the book is actually about understanding Englishness. It’s about Marmite, umbrellas, wonky teeth, sporting innovation and heroic failure. It’s about bad food and royalty and Hugh-Grant type characters. It’s as diverse as the nation itself.’

And what about the divide? Is there really such a thing as one Englishness? We might be a tiny island, but geographically and socially we are arguably one of the most diverse nations in the world. There is the obvious North/South divide, but there are more nuanced differences across the counties that make up England.

Shortly before I handed in my manuscript, my editor emailed me. ‘Do you think you could call it British?’ he asked. My heart sank, but it also gave me the resolve to lift my head and puff out my chest.

I am English (sort of) and I am proud of it, and this is my story of Living Englishly.

CHAPTER ONE

‘Sunshine is delicious, rain is refreshing, wind braces us up, snow is exhilarating; there is really no such thing as bad weather, only different kinds of good weather.’

John Ruskin

Millbank