ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

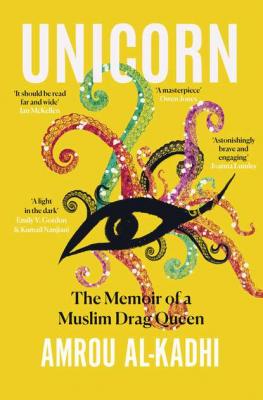

Unicorn. Amrou Al-Kadhi

Читать онлайн.Название Unicorn

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780008306083

Автор произведения Amrou Al-Kadhi

Жанр Религия: прочее

Издательство HarperCollins

There were some other Arab students at the school – three in my year group – and I tried to befriend them. During Ramadan, we all inevitably hung around together as the white contingent of the school ate in the cafeteria, but I was quickly ostracised by them. The three boys saw themselves as tough sub-cultural gangsters, and my limp wrists immediately excluded me from the poker table. In case you haven’t already worked it out, I was a very effeminate boy – even an ant could have told you I was gay – and so I was exiled from this male Muslim cluster for being, to use their vocabulary, a ‘faggot’. To be taunted by the only other Arabs in the school took its toll, and so I believed that a mastery of the English language would give me a chance of integrating into the school’s mainstream cultural contingent.

This feeling intensified in 2003, when I was thirteen. For 2003 was of course the year that Britain joined forces with America to invade Iraq, the country my family is from. There was little discussion of it among my peers, and in truth, I was also disengaged, even though I could hear the tremor of bombs in the background when I spoke to my grandmother in Baghdad. All I knew was this: Iraq was the baddy, and Britain, which was now my home, was the goody. With an aching desire for a place to belong, and having learnt time and time again that Arabs didn’t want me, I believed that an A* in English would effectively qualify as my citizenship test. I spent most weekends reading my way through the British literary canon, from Austen and Brontë to Shakespeare (and yes, a dose of J K Rowling). I ingested the words of the English literary greats – it was like undergoing cultural conversion therapy – so that my right to speak it could not be called into question. Whenever I slipped up, I punished myself harshly.

Again, it was coursework that was to be my undoing. The first assignment was for us to write a short story (mine was about a boy who ran away from his family, only to get lost in the woods and freeze to death – make of that what you will). I had armed myself with a canon of metaphors and similes, and all but slept with the marking criteria to make sure I had this down. We were assessed according to an exam-certified chart, which asked the teacher to score everything from our use of verbs to the complexity of our punctuation choices. (A message to all teachers reading this: if you suspect that your student might have OCD, for the love of Lucifer please do not show them a strict chart of rules to be adhered to. It has the opposite effect of an anti-depressant.) I worked extraordinarily hard on my piece of coursework. I went through thirty-two drafts, to be precise, and made sure I had included everything mentioned on the mark scheme I had studied. I felt a huge sense of relief when I handed it in on the Friday before a week of half-term holiday.

When I got home, the always agitated angel on my left shoulder, who prohibited me ever feeling happy for more than a fleeting moment, impelled me to look at the coursework I had just submitted. I read it through, my finger trembling as it scrolled on the desktop mouse, terrified that a glaring mistake might explode in my face at any second. After a nail-biting twenty minutes, I reached the final paragraph, and was almost out of the woods. When there it was. A disaster worse than I could possibly have imagined: I had forgotten to use a comma in a sentence that needed one.

An iron rod of panic whacked my chest. I felt quite genuinely that life was no longer worth living. My first port of call was to investigate why I had been so careless as to omit a comma; I read each of my thirty-two drafts to track when I had accidentally erased it with a backspace. I then downloaded every single examiner’s report about this GCSE unit, to ascertain what this absent comma would cost to my life. I then tried to find Ms Clare’s number on every school document that was in the house – no luck. That evening, I refused dinner, and even screamed into my pillow in bed. For the upcoming week’s ‘holiday’, I was so fatigued with depression that I spent all of it bed-bound, barely able to eat, let alone talk. I limped through the week with the hope that I might be able to convince Ms Clare – who had said that this date was the absolute deadline – to allow me to swap in the page with the forlorn little comma.

It felt, and I’m not exaggerating, like a life-or-death situation. Doing perfectly at school was the only tangible thing I had in my control, and without it, my desires and transgressions would take over me like a rabid infection. I was plunged into a low so deep that by the end of the week, I went in the kitchen to look for a knife. I needed to punish myself for this cataclysmic failure. I rummaged around the kitchen drawer, searching for the sharpest knife I could find. My mournful week in bed had completely drained me of life, and I was searching desperately for a way to feel something. Of course, the burdened-with-paperwork angel on my left shoulder would not allow comfort or joy to be the solution, so sharp pain and punishment was the most natural thing for my brain to seek out. I picked up the knife, and pressed the flat metal side against my wrist. The cold titillated my veins, which bulged out of my skin, almost asking to be sliced. I turned the knife ninety degrees, so that its blade teased my skin. But my right hand, whose shoulder was home to the angel that recorded good deeds, refused to move. I returned the knife to the drawer, and went back to my bed. Oh, and in case you’re dying to know the conclusion of this nail-biting saga, the benevolent Ms Clare of course allowed me to replace the document with the new, correct page.

My decision not to cut is a moment that replays in my head very frequently, and I question what it was inside me that resisted the impulse. Perhaps it’s because there’s quite a marked distinction between being self-punishing and being self-destructive. Yes, the good angel on my right shoulder was almost vanquished, but some semblance of it was still there. And the angel on my left wasn’t a devil, but a good angel that had fallen with sin, causing me to be a deeply guilt-ridden child. It was inherently a good angel. Self-destruction is obliterative and nihilistic – you believe you are worth nothing – while self-punishment is an oddly abusive form of self-improvement. You punish yourself to preserve something deep in your core, which you innately believe might be worth saving, even if it’s tarnished, feeble, and almost gone. By the age of fourteen, pretty much every cell of my being was infected with a cancer that told me I was rotten. But there were a few, just a few cells, that were healthy, somewhere. As a way to keep that little cohort of survivors safe, I continued to make academic perfection my mission, and punished myself whenever I fell short, for I had an aching need to show the world this perfect part of me – it was the only thing that contradicted everything else the world was telling me.

This unhealthy drive for perfection is not uncommon among queer people. You see it very visibly among gay men, many of whom are driven by the obsession to obtain the most perfect muscular physique, say. For as a queer person, it is a mathematical certainty that you will be hit with a feeling that you have failed – by your family, your God or your society – and the crack in your being that this causes, however small or big, can bring with it a drive for external markers of success that might somehow repair it. In moments like the comma episode, I felt as though the crack was going to swallow me whole.

At the age of fourteen, I made the decision to stop speaking Arabic. I was never entirely fluent, but I could hold my own in a conversation, understood it near-perfectly, and could read it with relative ease. But my proficiency dwindled the longer I lived in