ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

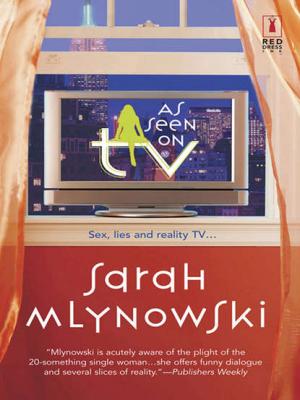

As Seen On Tv. Sarah Mlynowski

Читать онлайн.Название As Seen On Tv

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781472091017

Автор произведения Sarah Mlynowski

Жанр Современная зарубежная литература

Издательство HarperCollins

“I don’t normally date four-year-olds. I like my women with a little more flesh.” He licks my breast, as if to make his point. “It was a kilt, by the way. And I only wore it to that costume party because you have a thing for Scottish men.”

He does aim to please.

The sun is finally seeping through the blinds. Steve has a full-length blackout shade on the window and the pitch-blackness freaks me out. I hate darkness. It makes me think about dying, and why would I want to worry about dying when I’m only twenty-four and in the arms of the man I love?

I’m going to need a night-light or something.

When I was sixteen and alone in my house I would jump at every noise, convinced a murderer was breaking in. Once I locked myself in the bathroom for over two hours, clutching a carving knife, curled up in the fetal position in the dry bathtub.

My father fully alarmed the house, knowing how jumpy I was, and twice I pressed the panic button in my closet, bringing the police over.

A car horn blasts for the tenth time in the last twenty minutes. How does anyone sleep in this city? It’s so loud. The alarm clock says seven-twelve. I duck under Steve’s arm and shimmy down the bed.

We normally wake up late on Saturdays, around one. I tiptoe into the bathroom and gently close the door. I like to brush my teeth before he wakes up. This way, when he wakes up and rolls on top of me, I can have a discussion with him without worrying what I smell like. I realize that I won’t be able to do this every morning for the rest of my life, which would be insane, but I’ve managed to do it every morning so far and he’s never awakened. I brush, spit, rinse, spit, repeat, then climb back into bed and pretend to be asleep.

3

Wonder Woman

Should you be concerned if your boyfriend lies about you?

We’re lying on the grass at Union Square Park. My head is on his stomach and every time I move, I scrape my ear against his belt buckle. I shift so that the ants don’t crawl up my skirt while Steve tells me about when he was a junior in college and his mother found a crushed cigarette in his jean pocket.

“Why was your mother still doing your laundry?” I ask. “You were twenty-one, right?”

“Not everyone has her own house when she’s sixteen.”

A cloud covers the sun and the sky looks like one of its lightbulbs has burst. “My father flew in once a month for a weekend,” I answer.

“If I were your father, I never would have let you live by yourself,” he says, puffing up his chest.

“He asked me to come with him. I said no.” Even though I am looking down at Steve’s feet, I can tell that he is shaking his head. Is he wearing two different socks? Yes, he is wearing two different socks.

“I wouldn’t have given you a choice. There’s no way I’d leave my sixteen-year-old daughter by herself. Especially after what you’ve been through.”

He says “been through” with dread and awe, like a nine-year-old girl asking her older sister what getting her period feels like. Dana called it the Double D effect. Divorce and Death. “First that, and now this,” mothers of friends would whisper, not wanting to look us in the eye for fear the bad luck would spread through the room like cancer. Snapping the shoulder straps of our bras would be our secret signal, our “they’re feeling sorry for us” or “they don’t know what we know” sign.

Sometimes Dana makes fun of these people, behind their backs or to their faces. “It must be so hard for your father,” one of her co-counselors said, a co-counselor who was new to camp. Dana couldn’t stand her, thought she was an airhead. “Not so hard,” Dana replied. “He left her three years before she died, and he’d been fooling around since the day he married her. At least he doesn’t have to pay alimony anymore.”

When my friend Millie’s parents separated in high school and she lost ten pounds from “not being hungry,” I tried to patiently coax her to have a slice of pizza, to get over it, but eventually I snapped. “For God’s sake, at least they’re not dead,” I yelled at her and then felt cruel and horrible and spent the next week apologizing.

Any kind of loss is painful. But after your mother dies, divorce seems like a sprained wrist, compared to an amputated hand.

Dana and I divide people into those who know what we know and those who don’t. A secret club with loss as our badge.

Steve doesn’t know. He looks into the murky and bottomless future and sees something sparkling and blue. I love it that he doesn’t know, but constantly worry about the day he will. Sooner or later everyone does.

His grandmother died last June. It was sad for him, she was his last remaining grandparent, but it didn’t exactly rock his world. He still laughed at the Letterman’s Top Ten list that night.

I think the funeral was harder for me than it was for him. I hate funerals. I don’t breathe well and the walls start to contract.

I met his grandmother a few times before she died. Steve brought me to see her whenever he came to visit me. We sat politely with her at her retirement home while she fed us stale chocolate and tea. She liked me right away, I don’t know why, but she kept grabbing on tight to my wrist. “I want to dance at your wedding,” she said and we blushed. “You have to do it soon, I don’t have that much time,” she’d say.

We’d wave her comment away (“don’t be silly, you have lots of time”) but what are you supposed to say to an eighty-seven-year-old?

“You can have this,” she said and pointed to the engagement ring she still wore. It was beautiful, platinum band, a large round diamond, two baguettes. We kept blushing and she kept insisting.

I wonder what happened to the ring.

Back to my validation.

“Dana was doing her master’s, the first one, so she was only an hour away from my dad’s house,” I say. “She made the drive at least once a week to keep an eye out for me.” Dana had reveled in the pop-by—she’d claim to be drowning at the library and then sneak into the house to make sure tattooed men and acid tablets weren’t decorating the furniture.

My dad had invited me to move with him to New York. What was he supposed to do, not take the promotion? I told him there was no chance I was going. No way. Have a good time. Enjoy. I’d visit. Tobias, the guy I had been in love with since the first day of my freshman year in high school had finally realized what I had been telepathically telling him for twelve months—that we were meant to hold hands and laugh and sneak kisses between classes. There was no way, no way, I was moving now that we were finally a couple.

The idea of senior year, of trips to the shopping center’s food court where we’d hog tables and not buy anything, of destination-less drives of where-should-we-go-I-don’t-know-where-do-you-want-to-go taking place in my absence made me feel claustrophobic and abandoned, as if I’d been waiting in the back of the storage cupboard between the winter coats, not knowing that hide-and-seek was long over.

I told my dad that after all I’d “been through” it would be too traumatizing to have to leave behind the final memories of my mother.

When I was eleven at summer camp, I found out a boy I liked didn’t want to go to the social with me. Humiliated, I locked myself in the wooden bathroom stall at the back of my cabin and sobbed and sobbed until Carrie, my father’s now girlfriend, and my then-counselor, knocked on the door and begged me to tell her what was wrong. I told her I missed my mother.

Unlike Carrie, my father should have known that excuse was full of crap.

Before my parents separated, we all lived in Fort Lauderdale. When I was three, my mother started