ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

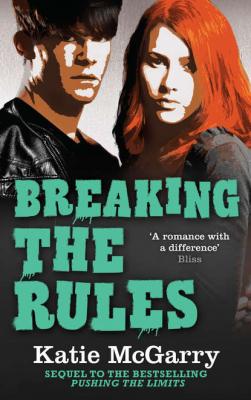

Breaking The Rules. Katie McGarry

Читать онлайн.Название Breaking The Rules

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781474008600

Автор произведения Katie McGarry

Издательство HarperCollins

She’s torn into me before, and the last time she did, she left me. My stomach plummets as I wonder if she’ll walk again.

Reaching behind me, Echo lifts the glass of champagne she brought with her from the gallery. “Well, there’s good news. It looks like we’ll be free tomorrow. The curator and I decided it would be best if we no longer share breathing space...or continents.”

Echo presses the glass to her lips, but I lift it from her hand. I’ve had a few of those tonight. More than a few. Enough that walking a straight line could be a problem.

My girl throws me a hardened expression that could send me six feet deep. “Damn, Echo. I’m not stealing your firstborn. I’m the drunk one, remember?”

She releases a sigh that steals the oxygen from my lungs, and she moves so that her back rests against me. I mold myself around her and nuzzle my nose in her hair. Echo inclines her head to the glass now in my possession. “How many of those have you had?”

* * *

I drink half the champagne while eyeing the prairie dog again through the gallery window. Champagne’s not my style, but free alcohol is free alcohol. “Not enough to understand that.”

“It’s a prairie dog,” she answers.

“With headphones.”

“It’s a commentary on how we are destroying nature.”

“That’s wood, right?” I ask.

Echo rolls her eyes, and I smirk. She hates it when I do this.

“Yes, the artist cut down a tree, used a chainsaw that required gas, and the whole process defeats the purpose.”

“Chainsaw?” These bastards are strange.

“Yes.”

I finish out the glass. “As I said, not enough.”

A couple exits the gallery, and they’re way too loud and way too full of themselves to peer in our direction. While I could give a shit about everyone inside, Echo cares, and the longing in her eyes as she watches them hurts me.

“Want to talk about the stuck-up bitch in there?” I ask.

“Nope.”

Good. Odds are I’d say things that would make Echo cry. “Then let’s get the fuck out of here.”

Noah and I slept deeply, we slept long, and then we held each other for longer than we should have. Now, checkout is looming.

Cross-legged on the middle of the bed, I cradle my cell and stare at three messages: one new voice mail, one missed call, one new text. Each one from my mom. There’s a pressure inside me—this overwhelming craving to please my mother, to gain her approval—that prevents me from deleting them. The memories don’t help...both the good and the bad.

Mom said she’s on her meds. She said that she’s in control of her life. If that’s true, is she mimicking my father’s parenting style by attempting to dominate my life?

Noah steps out of the bathroom fully dressed, and his hair, still wet from his earlier shower, hangs over his eyes, leaving me unable to read his mood.

“Did you call her?” he asks.

“No.” I pause. “But what if I did?”

Noah shrugs then leans his back against the wall. “Then you did. I don’t claim to understand, but I promised you back in the spring that I’d stand by you. I’m a man of my word.”

He is. He always has been. “But you don’t agree that I should call her.”

“Not my decision to make.”

I shift, uncomfortable that Noah’s not completely on my side. “I’d like to know you support me.”

“I support you.”

“But you don’t approve.”

“You need to stop looking for people’s approval, Echo. That’s only going to lead to hurt.”

My spine straightens. “I didn’t ask for a lecture.”

“You asked me to be okay with you contacting the person that tried to kill you. Forgive me for not setting off fireworks. You want to call her, call her. You want to see her, then do it. I’ll hold your hand every step of the way, but I don’t have to like seeing her in your life.”

His words sting, but they’re honest. The phone slides in my clammy hands. “I won’t call her today.”

“Because that’s your decision,” Noah says. “Not because you’re trying to please me.”

We’re silent for a bit before he continues, “I called the Malt and Burger in Vail. They can fit me into the schedule this week. If I want in, they can give me the walk-through of the restaurant this evening.”

A sickening ache causes me to drop a hand to my stomach. A week. We were supposed to travel back to Kentucky today. We were going to take another route so that I could try new galleries. But Noah has this need to find his mom’s family. He desires a place to belong.

Just like me.

If he wants to search for them, I can’t be the person standing in the way. “You should ask them to schedule you.”

“What if my mom’s family is bad news? Why would I want them in my life?”

“I don’t know.” It’s a great question. One I deal with daily. Maybe if we go, Noah will finally understand my struggle with my mother. “Let’s do this. Let’s go to Vail.”

Noah cuts his gaze from the floor to me. “This means you’ll be giving up visiting galleries on the way back.”

It will. Granting him this can cost me my dreams, but I’ve had enough time, and I guess I’ve failed. “There are probably galleries in Vail.” Hopefully.

“We’ll stay in a hotel the whole time. I’ll pay.”

“Noah...” My voice cracks. “No. I’m fine with the tent or I can help pay—”

“Let me do this,” he says, and the sadness in his tone causes me to nod.

“So we’re still heading west,” I say.

“West,” he responds.

My head pulses with the same speed as the cursor on the computer at the Vail Malt and Burger. Champagne hangovers suck.

“Clock in as soon as you walk in, and clock out the moment your shift is done and this is where you put your orders, you hear me?” The manager of the Malt and Burger is in the process of explaining to me the way “his” restaurant runs. He’s a six-two, two-hundred-and fifty-pound black man who, like the other managers throughout the summer, thinks he’s the only one that uses the system of sticking the paper orders over the grill. Two words: corporate policy.

“Got it,” I answer.

“You hear me?” he asks with a wide white grin. “It doesn’t leave the grill until it hits one hundred and sixty degrees.”

“Yeah, I hear you.” Food poisoning’s a bitch.

He slaps my back and if I wasn’t solid, the hit might have crushed me. “Good. Called