ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

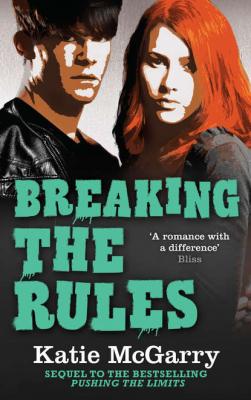

Breaking The Rules. Katie McGarry

Читать онлайн.Название Breaking The Rules

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781474008600

Автор произведения Katie McGarry

Издательство HarperCollins

It’s how I’d love to respond to the curator tipping her empty champagne glass at the floor-to-ceiling painting in front of us, but admitting such things will hurt the fragile reputation I’ve established for myself this summer in the art community. Instead, I blink three times and say, “It’s beautiful.”

I glance over at Noah to see if he caught my tell of lying. He bet me that I couldn’t keep from either lying or blinking if I did lie for the entire night. Thankfully, he’s absorbed in a six foot carving of an upright prairie dog that has headphones stuck to his ears. If I lose, I’ll be listening to his music for the entire car ride home from Colorado. There’s only so much heavy metal a girl can take before sticking nails into her ears.

In a white button-down shirt with the sleeves rolled up, jeans and black combat boots, Noah shakes his head to himself before downing the champagne in his hand. Absorbed was an overstatement. Prisoners being water tortured are possibly having a better time.

Noah stops the waiter with a glare and switches his empty glass for a full one. He’s been scaring the crap out of this guy all night and at this rate, Noah may get us both kicked out, which may not be bad.

“I heard you tried to secure an appointment with Clayton Teal so he could see your paintings.” The curator’s hair is black, just like I imagine her soul must be, yet I force the fake grin higher on my face.

“I did.” And he rejected me, or rather the assistant to his assistant rejected me. I can’t sneeze this summer without someone gossiping about it. I swear this is worse than high school. It’s been months since graduating from what I thought was the worst place on earth, and I’ve descended into a new type of hell.

“Little lofty, don’t you believe?”

“I sold several paintings this spring and—”

She actually tsks me. Tsks. Who does that? “And you don’t think your mother had anything to do with those sales?”

My head flinches back like I’ve been slapped, and the wicked witch across from me sips her champagne in a poor attempt to mask her glee.

“Well?” she prods.

I tuck my red curls behind my ear. “My work speaks for itself.”

“I’m sure it does.” She gives me the judgmental once-over, and her eyes linger on the scars on my forearms. The black sleeveless dress shrinks against my skin. I’ve only had the courage to show my arms since last April, and sometimes, as in now, that courage dwindles.

In high school, no one knew how the white, red and raised marks had come to be on my arms, and for a long period of time, neither did I. My mind repressed the night of the accident between me and my mother. But with the help of my therapist, Mrs. Collins, I remember that night.

As I’ve traveled west this summer, visiting art galleries, I’ve discovered a few people in my mother’s circle are aware of how I had fallen through her stained-glass window when I had tried to prevent her from committing suicide.

Unfortunately, I’ve also met a few people who loathe my mother and prefer to slather their displeasure with her like a poisoned moisturizer onto my face.

“She contacted people, you know?” she says. “Telling them that you were traveling this summer like a poor peddler and that she’d be grateful if they showed you some support.”

It appears this woman belongs to the I-hate-your-mother camp, and the sole reason I’ve been asked to this art showing is for retribution for some unknown crime committed by my mother. A person, by the way, I no longer have contact with. “Would you have been one of those people she called?”

She smiles in the I-drown-kittens-for-fun sort of way. “Your mother knows better than to call me.”

“That’s nice to know.” I half hope my mother dropped a house on her sister and that she’s next.

The curator angles away from me as if our conversation is already done, yet she continues to speak. “A piece of advice, if I may?”

If it’ll encourage her to pour water over herself so that she’ll melt, I’m all for advice. “Sure.”

“There’s no skipping ahead. Everyone has to pay their dues and you, my dear, the daughter of the great Cassie Emerson, are no exception. Using your mother’s name, no matter how many people are misguided into believing her work is brilliant, is no substitute for actual talent. I’m taking this meeting with you tomorrow because I promised a friend of mine from Missouri that I would if he agreed to feature some of my paintings. Do us both a favor and don’t show.”

I know the man she refers to. He was one of the last to buy a painting from me and since that day in June, I’ve hit a dry spell. The smile I’ve faked most of the night finally wanes, and Noah notices as he sets his glass on the outstretched prairie dog’s hand.

I had two goals for this summer. Number one: to explore my relationship with Noah, and that has proven more complicated than I would have ever imagined. Number two was to affirm to myself and the art world that I’m a force of nature—someone separate from my mother. Regardless of what my father believes, that I’m capable of making a living with canvas and paint and that I have enough talent to survive in an unforgiving world.

The curator turns to walk away, but my question stops her. “If you detest me so much, then why invite me tonight?”

“Because,” she says, and her eyes flicker to my scars again. “I wanted to see for myself if the rumors were true. If Cassie really did try to kill her daughter.”

Wetness stings my eyes, and I stiffen. I wish for Noah’s indifferent attitude or one of his non-blood sister Beth’s witty comebacks. Instead, I have nothing, but this witch didn’t completely break me. She was the first to look away then leave.

The corners of my mouth tremble as I attempt to smile. Realizing that faking happiness is completely out of the realm of reality, I let the frown win. But I’ll go to hell before I cry in front of this woman. I release a shaky breath and will the tears away.

A waiter passes and in one smooth motion I grab a glass of champagne off his tray and hurry for the door. My heart picks up pace, and my throat constricts. This isn’t how the summer was supposed to go. I was supposed to evolve into someone else...someone better.

I slide past a couple gesturing at a painting, and the glass nearly slips from my hand when I ram into a wall of solid flesh. “What’s going on, Echo?”

“Nothing.” Something. Everything. I pivot away from Noah, not wanting him to see how each seam of my fragile sanity is unraveling one excruciating thread at a time in rapid succession.

Noah’s hand cups my waist, and his chest heats my back as he steps into me. “Doesn’t look like nothing.”

I briefly close my eyes when his warm breath fans over my neck, and his voice purrs against my skin. It’s a pleasing tickle. Peace in the middle of torture.

“Look at me, baby.” When I look up, Noah’s beside me, and his chocolate-brown eyes search mine. “Tell me what you need.”

“To get out of here.” The words are so honest that they rub my soul raw.

Noah places a hand on the small of my back and in seconds we’re out the front door and into the damp night. Drops of water cling to the branches and leaves of the trees. Moisture hangs in the air. Each intake of oxygen is full of the scent of wet grass. While inside experiencing my own hurricane, it rained outside.

She contacted people, you know? I didn’t know. I had no idea, and the thought that any of my success belongs to Mom kills me. A literal stabbing of my heart, shredding it to pieces.

Resting the champagne glass I’ve now stolen onto the hood of the car, I tear into the small purse dangling from my wrist and power on my phone. The same words greet me: one new message.

Not