ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

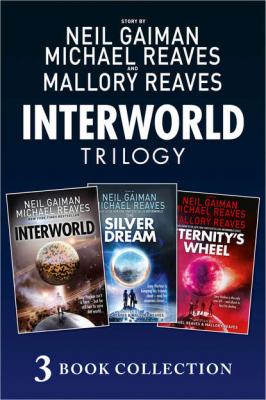

The Complete Interworld Trilogy: Interworld; The Silver Dream; Eternity’s Wheel. Нил Гейман

Читать онлайн.Название The Complete Interworld Trilogy: Interworld; The Silver Dream; Eternity’s Wheel

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780008238063

Автор произведения Нил Гейман

Жанр Детская проза

Издательство HarperCollins

… a gray sky. Saw that I was standing on the turret of a sad-looking castle. The whole place felt like an empty stage set, no longer in use. I couldn’t see anyone anywhere around.

“Okay,” I said to Hue. “Let’s go find the dungeons.”

THIS IS HOW TO find dungeons, if you ever have friends in durance vile in a castle somewhere:

Try to keep out of sight. Find the back stairs. Then just keep going down until there isn’t any more down to go, to where the corridors are narrow and smell of damp and mildew, and it’s dark enough that, without the weird light that goes with you (if you’re lucky enough to have a mudluff coming along) you can’t see a thing. When you get to that place, I guarantee the dungeons are just around the corner.

The castle was more or less deserted. I ducked out of sight when I heard footsteps at the other end of a corridor, but that was all. And the people going past looked more like movers: They wore white overalls and were carrying chairs and lamps away with them. They looked like they were closing the place down.

I found the dungeons in about twenty minutes, no problem.

Well, one small problem—they were empty.

There were nine cells, nine windowless holes in living rock, with heavy iron doors that were solid save for small barred windows. All of them were empty. The only sounds were the skitter and chitter of rats and the dripping of water on mossy stones. I took a chance and shouted their names: “Jai! Jo! Josef!” But there was no reply.

I sat down on the stones of the dungeon floor. I’m not ashamed to say I had tears in my eyes. Hue flooped from around me and bobbed in the air beside me, patches of glow moving across his surface.

I said, “I’m too late, Hue. They’re probably all dead by now. Either they got boiled down like the HEX people said, or they died of old age waiting for me to come back. And it was …” I was going to say my fault, but I wasn’t sure that it was, really.

Hue was trying to attract my attention. He was floating in front of my face, extruding little multicolored psuedopods.

“Hue,” I said, “you’ve helped a lot so far. But I think we’ve come as far as we can now.”

An irritated crimson blush crossed the little mudluff’s bubble surface.

“Look,” I said. “I’ve lost them! What are you going to do? Tell me where they are?”

Hue’s surface shimmered, and then became whirls and clusters of stars in a night sky above and below. It was a place I recognized. Jay and Lady Indigo had called it the Nowhere-at-All. The Binary people called it the Static. By those or any other names, it was the fringe area of the In-Between, the long route for traveling between the planes.

“Well, even if that’s where they are,” I said, “there’s no way I can follow them there.”

But Jay’d followed me, hadn’t he? He got me off the Lacrimae Mundi.

It could be done, then.

But I didn’t know how to do it. I could only Walk through the In-Between itself. To reach the Nowhere-at-All would require knowledge of a whole different set of multidimensional coordinates, from someone familiar with those levels of reality—

I looked up. “Hue?” I said.

The mudluff moved away from me, slowly, foot after foot, until he was at the end of the dank corridor. And then he came barreling toward me, faster than a flowerpot falling from a window ledge, and even though I knew what he was going to do, I couldn’t help flinching back as he filled my vision and there was a—

poppp!

—and my world imploded into stars.

The mudluff was nowhere to be seen. Instead, everything felt very familiar. I got that déjà vu feeling of I’ve been here before, but of course I hadn’t: Last time I was falling through the Nowhere-at-All Jay was falling beside me, and we were falling away from the Lacrimae Mundi.

Now the wind between the worlds was whipping at my face and tearing my eyes; and the stars (or whatever they are, out in the Nowhere-at-All) were blurring past; and I was flailing, terrified at the emptiness of nothing but more terrified still because now I wasn’t falling away from anything.

I was falling toward something.

Imagine a doughnut or an inner tube—your basic toroidal shape. Paint it with something black and kind of slimy. Now take five of these and twist and turn and meld them together like those balloon thingies street artists sometimes do for kids—although I think that if you made one that looked like this for a kid, he’d start crying and not stop. Still with me? Now make the whole thing the size of a supertanker. Last, cover every curving surface of what you now have, which is a big black tubular evil thing, with derricks and towers and machicolated walls and ballistae and cannons and gargoyles and …

Get the idea?

This was not something you wanted to be falling toward. Trust me. It was something you wanted to be falling away from, as fast as possible.

But I didn’t have a choice.

I squinted my eyes against the wind. There were two or three dozen smaller ships—galleons, like the Lacrimae Mundi, and ships smaller and faster than her—arranged around the big black thing. They looked like ducks escorting a whale.

I knew I was looking at Lord Dogknife’s attack armada and dreadnought. It was the only thing it could be. They were beginning the assault on the Lorimare worlds.

I had finally found where my friends were being held prisoner—assuming they hadn’t already been reduced to Walker soup. The problem was that in a minute or so I was going to hit it like a melon dropped from a skyscraper, and there wasn’t a single thing I could do about it. The Nowhere-at-All isn’t outer space. It has air and something like gravity. If I hit the ship, I was dead. If I missed—and I had about as much chance of that as an ant missing a football field—I’d keep falling forever, unless I could open a portal into the In-Between, and there was no guarantee of that. I’d only made it last time because Jay was with me.

What would Jay do? I asked myself.

I thought you’d never ask, said a voice in the back of my head. It sounded like my voice, only a decade older and infinitely wiser. It wasn’t Jay or his ghost or anything like that. It was just me, I guess, finding a voice that I’d listen to.

You’re in a Magic region, now, Jay’s voice continued. Newtonian physics are more of a suggestion than a hard-and-fast rule. It’s strength of will that’s important.

It was a rehash of the lectures from Practical Thaumaturgy, or what we called “Magic 101.” “‘Magic’ is simply a way of talking to the universe in words that it cannot ignore,” our instructor had told us, quoting someone whose name I’ve already forgotten. “Some parts of the Altiverse listen—those are the Magic worlds. Some don’t and would rather that you listened to them. Those are the Science worlds. Understand that, and the whole thing is kind of simple.”

Of course, “kind of simple” is a relative concept in a school where even the remedial classes would give both Stephen Hawking and Merlin the Magician nosebleeds. Still, I had learned enough to know that the place I was in now was a place of raw and unfocused magic. A “subspace” that worked more by the rules of a collective consciousness than by mechanistic principles.

Will. That was the key.

You got it, said Jay in the back of my head. Now bring it home.