ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

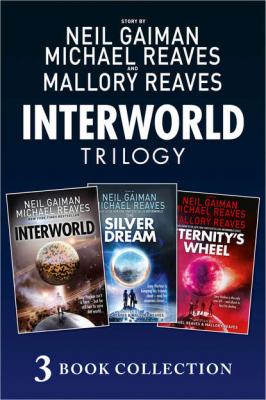

The Complete Interworld Trilogy: Interworld; The Silver Dream; Eternity’s Wheel. Нил Гейман

Читать онлайн.Название The Complete Interworld Trilogy: Interworld; The Silver Dream; Eternity’s Wheel

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780008238063

Автор произведения Нил Гейман

Жанр Детская проза

Издательство HarperCollins

Either way, between periods, he came over to me from behind and took me by surprise, knuckling me hard in the kidney.

It all happened kind of fast, then.

I dropped my center of gravity by bending my legs slightly, took a step back and slid my other foot over into a modified cat stance (and don’t ask me how I knew it was called that). I grabbed his wrist, bent it in one of the few ways wrists were not designed to bend, pulled him over and brought the edge of my other hand down on the back of his neck. In just over a second Ted had gone from causing me pain to writhing on the ground in agony at my feet. I shut off the autopilot that had taken over just in time to keep from performing the last movement in the sequence, which I knew (again, don’t ask me how), would have resulted in a very dead Ted.

He got to his feet and stared at me as if I’d sprouted green tentacles. Then he ran from the room, which was good, as I was completely frozen. I didn’t know what I’d done. I didn’t know how I’d done it. It was as if the muscles had known what to do and didn’t need me.

I was just glad that no one else had seen it. Things went on like that for about two weeks.

“You ought to be kidnapped by aliens more often,” said my dad one evening over dinner.

“Why?”

“Straight A’s, for the first time in human memory. I’m impressed.”

“Oh.” Somehow it didn’t seem that cool. Schoolwork was pretty simple now: It was as if I knew how hard it could be and what I was capable of doing. I felt like a Porsche that had learned it wasn’t a bicycle anymore but was still taking part in bicycle races.

“What does ‘Oh’ mean?” Mom picked up on that immediately.

“Well.” I gestured with a stalk of broccoli. If you wave it around enough, sometimes they don’t notice you’re not eating it. “It’s just math and English and Spanish and stuff. It’s not like it’s hyperdimensional geometry or something.”

“Not like it’s what?”

I thought about what I’d just said. “Dunno. Sorry.”

Most of the time I forgot about my thirty-six-hour loss. But when I fell asleep at night and, sometimes, when I woke up in the morning, I could feel it at the back of my head. It itched. It tickled. It pricked and it tingled. I felt like I was missing a limb in my head; as if an eye that had opened had closed forever.

I was fine, unless I was lying in the dark. And then it really hurt. I’d lost something huge and important. I just didn’t know what.

“Joey?” said Mom. Then she said, “You’re getting too big to be Joey. I suppose you’ll be Joe, soon.”

My upper arms shivered with goose pimples. It was there, again. Whatever it was. “Yeah, Mom?”

“Could you take care of your brother for a few hours? Your father and I are going to visit my gemstone supplier. There’s a semiprecious stone from Finland I’ve never heard of he says would be perfect for me.”

Did I mention my mom designs and makes jewelry? It was a kind of hobby that got a bit out of control, and it had paid for the extension on the house.

“Sure,” I said. The squid is a cool little kid. He’s actually kind of fun for an eighteen-month-old. He doesn’t whine (much) and he doesn’t cry unless he’s tired, and he doesn’t follow me around too much. And he always seems pleased when I play with him.

I went up to his room in the annex. Every time I walked up those stairs I found myself wondering if the nursery was going to still be there this time.

It’s like those weird paranoid thoughts that go through your head when there’s not enough going on, like when you’re in the bus on the way home from school and you wonder if maybe your parents moved away without telling you. You must have had them, too. I can’t be the only one.

“Hey, squidly,” I said. “I’m going to be looking after you for a couple of hours. You got anything you want to do?”

“Bubbles,” he said. Only he said it more like “Bub-bells.”

“Squid, it’s the beginning of December. Nobody blows bubbles in this weather.”

“Bub-bells,” said the squid sadly. His real name is Kevin. He looked so dejected.

“Will you wear a coat?” I asked. “And your mittens?”

“Okay,” he said. So I went down to the kitchen and made a bucket of bubble mixture, using liquid dishwashing soap, a jigger of glycerin and a dash of cooking oil. Then we put our coats on and went into the yard.

The squid has a couple of giant plastic bubble-blowing wands, most of which he hadn’t used since September, which meant that I had to find them, and then I had to wash them, as they were caked with mud. By the time we were ready to start blowing bubbles, it was snowing gently, big flakes that spun down from the gray sky.

“Hee,” said the squid. “Bub-bells. Ho.”

So I dipped the bubble wand into the bucket, and I waved it in the air; and huge multicolored soap bubbles came out from the plastic circle and floated off into the air; and the squid made happy noises which weren’t quite words and weren’t quite not; and the snowflakes touched the bubbles and popped the little ones, and sometimes the flakes landed on the bigger bubbles and slid down the sides of them; and every soap bubble as it floated away made me think of …

… something …

It was driving me crazy that I couldn’t quite tell what.

And then the squid laughed and pointed at a bobbing bubble and said, “Hyoo!”

“You’re right,” I said. “It does look like Hue.” And it did. They’d taken everything from my head, but they couldn’t take Hue. That balloon looked just like the …

… just like the mudluff that was …

“ … It’s a multidimensional life-form …”

I could hear his voice saying it, under that swimming, finger-painted sky …

Jay.

I remembered him, lying bloody on the red earth after the monster attacked.…

And then it came back. It all came back, hard and fast, while I was standing out in the snow with my baby brother, blowing bubbles.

I remembered it. I remembered it all.

I COULD WALK AGAIN.

Don’t ask me how. Maybe there was a glitch in whatever brain-scrubbing gizmo they used on me. Maybe Hue was some kind of unanticipated variable they hadn’t programmed (or deprogrammed) for.… Whatever. All I know is, standing there in our backyard, shivering in that light dusting of snow, watching my little brother happily chasing those bubbles around, a series of firecrackers was going off in my head, each one illuminating a memory that hadn’t been there before.

I remembered everything: the grueling days and nights of study and exercise; the infinite diversity of my classmates, all variations on a theme that was Joey Harker; the tiny supernovae going off apparently at random in the Old Man’s artificial eye; the seething Technicolor madness that was the In-Between …

And the milk-run mission that had gone wrong, being captured once again by Lady Indigo and my rescue—mine and only mine—by Hue.

I