ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

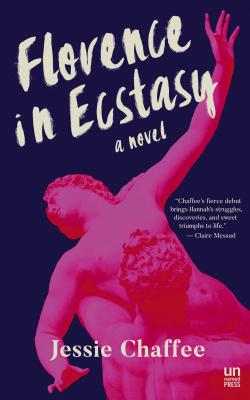

Florence in Ecstasy. Jessie Chaffee

Читать онлайн.Название Florence in Ecstasy

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781944700416

Автор произведения Jessie Chaffee

Жанр Современная зарубежная литература

Издательство Ingram

“I don’t,” I say. “Nothing happened. I’m not looking for anything here.”

“Va bene.” She shrugs. “Just thought you should know. These men—you can never tell.”

Adriana looks back at us as we’re funneled into the square.

“Do you study English?” I ask her, and she nods.

“Yeah, she speaks it perfectly,” Francesca says loudly. Then to me, “When she talks, that is. Honestly, sometimes I feel like I’m living in a church.”

I look at Adriana, but she’s aleady broken away and her lantern becomes one of many as she disappears into the crowd, the orb swinging side to side.

Francesca pulls me to the stairs of the old foundling hospital that frames one edge of the piazza. Along its portico, in the spaces where the columns burst into arches, is a line of medallions stamped with swaddled children, white against powder blue. I look up at their bodies, tiny from here, and wonder when I will bleed, if I will bleed, my insides parched and brittle. At the end of the building, a large wooden wheel is set into the wall. I’ve read that centuries ago people could abandon their unwanted offspring there: place the child on the wheel and rotate the little foundling into the orphanage anonymously.

Tonight the piazza is filled with children, though, from the youngest sitting on their parents’ shoulders to those Adriana’s age, who anxiously search the crowd for other teens. Each child clutches a paper lantern.

“It’s part of the Feast of the Madonna,” Francesca explains as we look out over the square. “I swear, there are more feasts and festivals in this city… Don’t get me wrong, I was raised Catholic. My parents put me through the ringer. You?”

“No. Not even close. My mother believes in yoga—that and work.”

“Ha. What about your father?”

“I think he goes to church now because of his second wife. Anyway, finding God didn’t change how he felt about us. He was still just not around.”

“Ho capito. Sorry. Anyway, tomorrow’s the big day,” Francesca says. “Birth of the Madonna. Back to church.”

The last bit of sun is lost behind the buildings and the air becomes sulfurous as each lantern is lit. Adriana reappears with another girl at her side, who greets Francesca quickly and then drops her voice to an excited whisper as Adriana leans her lantern toward us. Francesca pulls out a lighter to spark the candle from below and the sun’s face ripples with light and shadow. Across the piazza, other lanterns glow to life, their patterns appearing. There are animal heads, starbursts, a Medici family seal. Adriana’s friend has a broadly grinning cat. The images blur as the crowd begins to move and Francesca takes my arm. We walk out of the piazza behind the two girls and join the stream of lights that flows, sparkling, between the old buildings.

“The parade goes up the river,” Francesca explains.

Suddenly there’s a shout from the crowd and one of the lanterns explodes. Its owner, a very young girl, begins to cry as bits of paper fall to the ground. Adriana and her friend look around, their eyes wild with anticipation.

“What was that?” I ask.

“Don’t worry,” Francesca says. “It’s normal. Some of the kids carry—what do you call it?” She purses her lips, then says, “Peashooters. Mostly boys.” Her phone rings. “Aspetta,” she says, glancing at it and smiling before picking it up. “Pronto? Sì… Yeah, I’m here with Hannah. You know Hannah… Sì, certo. Ponte alle Grazie. Va bene. A dopo.” She snaps it shut. “Look—there’s one.”

A boy darts through the crowds ahead of us. He raises the little peashooter to his lips and takes aim at a glowing lion. He blows and, in a moment, the lantern is deflated.

Francesca shakes her head. “Just like men, you know?”

He takes aim at another lantern but misses this time. Night has fallen, and above us, people are leaning out their windows to watch the lanterns pass. We take one turn and then another before we reach the river, where bodies pour in from the other streets to join the unbroken line of light. On the Arno, small glowing boats are carried fast by the current until they are caught in a mass at the base of the Ponte alle Grazie.

“Peter!” Francesca shouts, and I see him leaning against the wall by the bridge. She grabs his hand as we pass and kisses him on the cheeks.

“Ciao, Hannah,” he says, flushed. Adriana looks back with a blank expression before she and her friend link arms and move ahead without speaking. He glances at Francesca.

“Non ti preoccupare,” she says. “It’s not a problem.”

“So you started in the piazza?” Peter asks, his voice bright. “It’s a great event. It only happens in Florence, you know.” He pauses. “We’ve missed you at the canottieri.”

“Thanks,” I say, though after Francesca’s gossip, I wonder who the “we” is. I try to remember the end of the night at the dance club—who saw me fall?—but the faces are gone, disappeared. More lost time.

“Have you been out on the water yet?” Peter asks.

“No, I don’t think I’m ready.”

“You should try. I can help you if you’d like. Francesca could, too. She’s not half bad.” Francesca hits his arm and Peter grins.

Around us the children begin to sing, the words become clearer as they repeat: “Ona, ona, ona. Ma che bella rificolona. La mia l’è co’ fiocchi e la tua l’è co’ pidocchi.”

What a beautiful lantern, mine is tied with bows. But the last phrase is confusing.

“Pidocchi?” I ask.

“Lice,” Francesca says.

“Why lice?”

She shrugs. “Who knows?”

“Because of the history,” Peter says, excited.

Francesca loops her arm through his. “The little professor. I told Hannah it was a Catholic thing. You going to show me up?”

“I’m not showing you up.” He laughs, pulling her closer and then turning to me. “It is a Catholic thing. But the holiday was also one of the biggest market days of the year. Farmers came in from the countryside to sell their goods, but there wasn’t enough space in the piazza—Santissima Annunziata—so they left the night before to get a spot.”

“Ah,” Francesca says, pleased. “So they came with lanterns.”

“Exactly,” Peter says.

“Ona, ona, ona,” the song continues, louder now. Up ahead at the next bridge the light is spreading horizontally as people disperse.

“And the lice?” I ask.

“Well, the farmers wore their best clothing. Coming to Florence was a big deal, you know. But the Florentines still saw them as lice-ridden peasants. And the children who lived in the city would shoot at their lanterns.”

“Sì.” Francesca laughs. “The Florentines are a bit arrogant, no? Hundreds of years, and nothing changes.” She sighs and leans her head on Peter’s arm.

“I should go,” I say as we approach the bridge. The parade is morphing into a party. The adults are gathering in groups, and the lanterns that have survived the snipers are falling forgotten to the street or becoming weapons themselves as children chase one another.

“I’m glad you came,” Francesca says warmly, embracing me.

Peter