ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

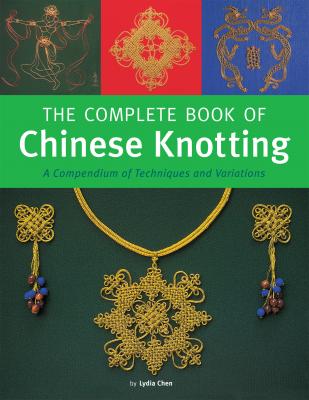

The Complete Book of Chinese Knotting. Lydia Chen

Читать онлайн.Название The Complete Book of Chinese Knotting

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781462916450

Автор произведения Lydia Chen

Жанр Сделай Сам

Издательство Ingram

The Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) witnessed a second peak in the use of knots. During this time, all present day basic knots became widely used. We can even see some outer loops being extended into complicated knots.

Buddhist statue, Western Wei Dynasty (CE 535– 556), from cave 102, Maiji Caves, Tianshui, Gansu Province.

Copper ornament, Han Dynasty 206 BCE–CE 220).

Right: Stone carving entitled “The Empress’s Devotee,” Northern Wei Dynasty (CE 386–534), in Bingyang Cave, Longmen Grottoes, Luoyang, Henan Province.

Far right: Portrait entitled “Seated Folks,” Southern Song Dynasty (CE 1127–1279). Photo courtesy Palace Museum, Taipei.

Clothing

Long robes with flowing sleeves, the traditional garb of both men and women in ancient China, had to be fastened at the waist with knotted sashes. Simple examples exist in paintings (pages 11 and 12). Gentlemen of the Zhou Dynasty (c. 1050–256 BCE) would carry a special device, a xi (page 9), tied to their waist sashes for untying knots. They were also fond of wearing elaborate belt ornaments hung from their sashes, composed of several small pieces of delicately carved jade with cord eyelets strung together with intricate knotwork.

Tang sculpture has preserved the designs of a handful of knots, some quite complex, that have survived to the present day. The prototype of the good luck knot (with only one layer of overlapped ear loops) can be seen in a hanging tassel on a statue of the Goddess of Mercy, Kuan Yin, dated to the Northern Zhou Period (page 3). Subsequently, the Buddha knot, which Buddhists hold as a symbol of all good fortune, was spotted hanging from the waist of another statue of Kuan Yin, dated from the Sui Dynasty, now in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City (page 4). The double connection knot was first discovered decorating the back of a sash on a Tang terracotta figure housed in the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto (page 4). On the same tassel is a Buddha knot. Indeed, a few double connection knots with outer loops, of which the knotting technique still remains elusive, are apparent on various stone Bhodisattvas from the Western Wei and Northern Qi periods (mid-sixth century). An elegant knot was found on the tassel of the empress’s devotee on the stone carving of the same name found in Bingyang Cave, Luoyang (page 12). The cross knot made its debut on a Tang Dynasty silk belt in the Tokyo National Museum. The image on page 4 shows a net bag tied from cross knots.

In the Southern Song portrait “Seated Folks” (page 12), some double connection knots with outer loops are clearly visible on the characters, but the knotting technique still eludes us. Since it only appears around the Southern Song–early Yuan period, it can serve as a diagnostic indicator for other artifacts.

Detail of a portrait,“The Lady with the Fan,”Tang Dynasty (CE 618–906).

Rubbing of the “Seven Scholars of the Bamboo Garden,” rubbing from a brick frieze, Danyang, Jiangsu Province.

Stone frieze entitled “The Emperor Praying to Buddha,” Bingyang Cave, Longmen Grottoes, Luoyang, Henan Province.

Ru yi (sacred fungus) knot, Tang Dynasty (CE 618–906). Photo courtesy Palace Museum, Taipei.

Furniture and Other Household Objects

Bronze mirrors, forged with rings on the back, were tied to walls by knotted cords (page 14), while bronze vessels from the Warring States Period, replicas of earthenware jugs, were decorated with a knotted network resembling the cords used to support their fragile antecedents. In various portraits from the Tang and Five Dynasties periods, Chinese knots occur beneath chairs, for example, in “The Lady with the Fan” (page 13), and in screens behind emperors’ seats. In fact, the first pan chang knot was found in a portrait of the Ming Emperor Xiaozhong (page 6). From the Song period, Chinese knots were used to decorate armrests. The predilection for Chinese knots is evident in all portraits of Song royalty, for example, Empress Zheng Zhong (page 14).

Accessories and Other Items

Umbrellas adorned with Chinese knots are abundant in the “Luo Goddess” scrolls dated from the Eastern Jin Period. They are also seen in the stone frieze, “The Emperor Praying to Buddha,” in the Bingyang Cave, Luoyang, Henan (page 13). Musical instruments embellished with knots can be seen in the brick frieze, “The Seven Scholars of the Bamboo Garden,” from Hu Bridge in Danyang, Jiangsu (page 13). During the Qing Dynasty, knots were widely used to grace objects in daily use such as ru yi, sachets, wallets, fan tassels, spectacle cases and rosaries. All existing basic knots, except the creeper and the constellation knots, also appeared on ornaments from the Qing Dynasty, regarded as the heyday of Chinese knots, where the outer loops were extended into other knots. As a decorative design on objects, the round brocade knot was first discovered on a Tang silver pot dug up in He Village, Xian (page 5). The tassel knot was discovered onTang a mirror (page 5) and the cloverleaf knot on a Song porcelain box (page 6).

Portrait of the Empress Zheng Zhong, Song Dynasty (CE 960–1279).

Longevity mirror, Han Dynasty 206 BCE–CE 220). Photo Courtesy of Palace Museum, Taipei.