ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

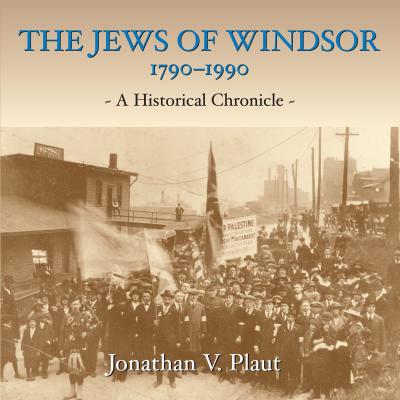

The Jews of Windsor, 1790-1990. Jonathan V. Plaut

Читать онлайн.Название The Jews of Windsor, 1790-1990

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781550029420

Автор произведения Jonathan V. Plaut

Жанр Зарубежная эзотерическая и религиозная литература

Издательство Ingram

Solomon and Sarah Glazer owned a second-hand store at 12 McDougall Street. The September 2, 1893, edition of the Evening Record, and the 1894–96 Windsor City Directory listed another second-hand dealer by the name of Isaac Jacobson. Benjamin Jacobson, who was working at the Malleable Iron Works, may have been Isaac’s son or his brother, since the 1899 city directory showed them living at the same address.82 Meyer Wartelsky’s name appeared in the directory as early as 1900.83 However, little else is known about him, except that he had a daughter who later lived in Detroit.

These Jewish immigrants were neither saints nor sinners but people with different customs and religious practices who erred at times like their Christian neighbours in their struggles to survive in a primitive community. The earliest pioneers made Windsor their home, established a viable Jewish community for their children and later generations, who still bear their names. Thus the seeds for future settlement were sown by a handful of Russian immigrants who remained either by choice or by stroke of luck. At this point, however, the future of the Jewish community in Windsor certainly seemed full of promise.

Chapter 3

A Community Takes Root

Windsor in the New Century

The first decade of the twentieth century saw active immigration to Canada, especially to the Prairie provinces, which needed more settlers to cultivate the vast agricultural lands. A similar growth also took place in Canadian cities, which were experiencing the twin dynamics of urbanization and industrialization. The establishment of Ford Motor Company of Canada in 1904 spawned a fourth Border City — Ford City — community, which grew rapidly to achieve town status and join the existing border municipalities. The automobile industry was sparked by the development of the internal combustion engine and moving assembly lines, which made mass production of low-priced automobiles possible. The application of these revolutionary manufacturing methods not only created thousands of jobs in the auto industry, but also stimulated the growth of numerous related businesses. Detroit had emerged as the world centre of this new economic bonanza and the Border Cities across the river were along for the ride.

Continuing to develop its position as a transportation centre and border gateway, Windsor’s ferry service expanded its operations beyond passengers and railway cars and added both grander, more luxurious pleasure vessels and new automobile ferries. The first railway tunnel under the Detroit River was opened in 1910, and it carried passengers as well as freight. Mass transportation — the ferries, railways and streetcars — were not yet ready to surrender to the automobile age. The Sandwich, Windsor, and Amherstburg street railway (SWA) that connected the Border Cities was purchased by the Detroit United Railways and expanded into a true interurban electric railway by 1907, extending from Tecumseh in the east to downriver Amherstburg. The following year, the Windsor, Essex, and Lakeshore Railway brought Essex, Kingsville, Leamington, and other county centres into the Border Cities’ sphere.

The industrial committee of City Council, supported by a progressive Board of Trade, actively sought industry and investment through bonuses and other incentives as well as through publicity and self-promotion. Municipally planned factory districts offered fully serviced properties in prime industrial areas. The Border Cities claimed to be the “Auto Capital of Canada,” if not the British Empire, and boasted of its title as the “Branch Plant Capital of Canada,” listing dozens of American firms that had taken advantage of favourable tariff regulations to expand their operations into Canada and the Empire.

Establishing a Permanent Community

At the same time that Windsor was growing and developing into a major industrial and economic centre, the fledgling Jewish community was also growing and developing — a process that was not always smooth.

Windsor’s founding Jewish community established their first synagogue in the 1890s, but the apparent cohesiveness of the little Jewish community assumed by outsiders, proved to be less harmonious in practice. Differences leading to arguments and lawsuits led to a proliferation of groupings and institutions; with others to follow.1

Before 1895, Windsor’s Jewish pioneers had relied on Detroit for most goods and services. However, as their community began to grow they wanted their own rabbi, Hebrew teachers for their children, kosher meat, an appropriate burial ground but most especially, a place where they could gather and worship together. Since the desire for such a place was very strong, a handful of determined people got together to establish the town’s first synagogue.

Photo courtesy of Windsor’s Community Museum P6138

Firehouse with part of the 1893 synagogue shown on the side.

Between 1888 and 1890, that nucleus of Windsor’s Jewish community, which included the Meretskys, Bernsteins, Bensteins, and Kovinskys, opened their homes to provide the initial shelters for the observance of Sabbath services.2 Two years later, a small house was found on Sandwich Street East (now Riverside Drive), where High Holidays services could be held.3 Since only the basement was available, the space was soon too small to accommodate the ever-increasing number of worshippers.

The First Synagogue

Windsor’s first synagogue was at 50 Pitt Street East.4 It was in a store rented for $5 a month, from either Herman Benstein,5 who then may have been the owner of the building, or from William Englander who, according to the Evening Record in 1895, was “said to own the synagogue.”6 Since it was next door to the fire hall, we might picture a group of pious gentlemen engaging in fervent prayer, oblivious to the clanging fire truck bells and other ambient street sounds piercing the atmosphere. The unavoidable co-existence with the noisy outside world must have added a light-hearted touch to an otherwise solemn situation.

Photo courtesy of Windsor’s Community Museum P6137

The beginnings of business in the Windsor area for the Meretsky family, with slight view of the synagogue in the 1890s.

To make services meaningful, the congregants acquired a Torah that was installed in a makeshift Ark on the upper floor of the building.7 The only available seats were a few ice cream parlour chairs, which Jacob Geller well remembered carrying up the very narrow staircase when he was a young child. To perform such religious functions as weddings, itinerant rabbis usually were brought over from Detroit. The first of these ceremonies is described in the following newspaper account, dated July 15, 1895:

A crowd of about 500 people were attracted into the little Hebrew church adjoining the fire department on Pitt Street last evening at 7 o’clock. It was the performing of the matrimonial functions that made Michael Brosen [sic, Rosen] of this city, and Lena Kalin [sic, Kahn, sister of Rachael Kahn Meretsky] of Bay City, Michigan, man and wife. A scene of this kind has not been witnessed in Windsor since three years, and as the little church boosts a flock of but twenty, Rabbi A.M. Ash-uskey [Ashinsky] of Detroit, united the contracting parties.8

A year later, the Pitt Street synagogue was already listed in the Windsor City Directory.9 However, anxious to observe other Jewish customs and practices such as having matzah for the Passover feast, the growing congregation wanted it to be more than a place of worship. In that connection, the Evening Record of March 21, 1899, carried an item that dealt with the fact that Windsor’s Jewish population had been

made to pay duty on a wagonload of unleavened bread by the local