ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

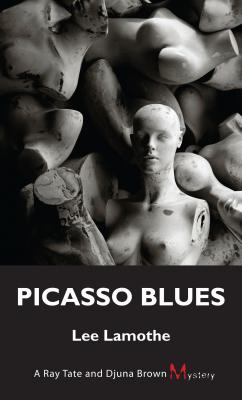

Picasso Blues. Lee Lamothe

Читать онлайн.Название Picasso Blues

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781554889679

Автор произведения Lee Lamothe

Жанр Ужасы и Мистика

Серия A Ray Tate and Djuna Brown Mystery

Издательство Ingram

Ronnie sagged a little. He looked like, given the choice, he’d rather take the beating. “I’m sorry, Djuna … Sergeant Brown.”

“Don’t tell me, Ronnie. Tell Misha.” There was a thick cudgel with dark stains at the business end leaning against the drawers on her side of the desk where he couldn’t see it. It wasn’t hers: it was called the Abo-Swatter and it had notches in it where the guys had tallied their Saturday night rodeos. There were a lot of notches, but none of them fresh. When she’d come up from the city, transferred back and promoted, she’d lined up the guys and told them where to head in. No one spoke to her after that except about the work, but she’d gone the distance in the cop trade and killed a man in the line and that came with its own respect, if not friendship.

“How we going to do this, Ronnie? Me or the elders?”

He looked at her.

She smiled, her hair spiky and jet black. She looked like a backup singer in the videos broadcast through his satellite dish over from Chicago. The handcuffs weren’t necessary. Everybody on the Rez loved something about her.

“Elders.” He sucked his lips. “Elders. I’ll take a tribal council. Okay?”

It wasn’t strictly legal under state law. Self-rule and tribal councils made the pale jowls in the state capital quake, preventing them from dispensing human mercy as though it was a gift, as if fairness and dignity were special rights to be bestowed.

She nodded. “Elders, okay. What they say goes. I’ll stand by it, you stand by it.” She came around the desk in her slippers, seeming not much taller standing up than she was sitting down. Even removing the handcuffs let her reveal her technique: she placed a gentle hand flat on his shoulder while she operated the key. Ray, her city cop, had taught her that. She was ready to jump away from him if Ronnie went off, to get the stick from behind the desk, to hope her guys outside the door came boiling in when she called out.

But Ronnie just massaged his thick wrists. He didn’t want to frighten her and waited until she’d stepped away before nodding his head and getting up off the chair. “I’ll be home, when they want me. The elders. Sergeant … Brown.”

As she pulled on her knee boots, she gave him a luminous smile of perfect little chicklet teeth and took her round hat from the peg by the door. “Ah, c’mon, Ronnie, man. My name’s Djuna. I’ll give you a drive.”

She felt like a city suburban mom piloting the Expedition. She wouldn’t let Ronnie ride chained in the cage in the back like a prisoner in case his Misha saw, although strictly speaking he was still in custody. The top of his head almost touched the headliner. He was silent beside her. There was a type, she knew, who went quiet, gathering in their mind the slights and grudges of the day, mixing them together like a violent brew that reached fission and the next thing you knew you were on the floor in incredible pain, going holy-fuck, and covering up your vital organs as the guy tried to kick you to death. She’d been there twice, each time when she walked into a Saturday-night bar powwow and sparked off some deep thinker for whom a uniform was the last crucial ingredient in the wild beverage percolating inside. Both times it was the Native men who waded in and got her free, protected her, wrestling the guy off her and out the door. They wouldn’t hold him for arrest; things weren’t that way and she had no right to expect that.

The Expedition knew the way. It smoothly rolled past the bent, perforated stop signs, heading out of town beyond the shacks and cracked foundations of the government houses. Djuna Brown drove with the big red ball on the floor behind her, but all the troops left theirs on the dash. She didn’t, because she wanted people to know it was her coming.

Ronnie didn’t seem to want to talk, so she let her mind muse, think about Ray Tate, something she’d thought she’d have stopped doing by now but instead did more frequently, wondering if he even remembered her.

When she drove off the rutted driveway of Ronnie’s sloping shack he was on his knees, forehead to forehead with Misha. She seemed to be comforting him. Ronnie’s mostly absent wife was in the doorway, a shapeless woman in a colourless shift dress, barefoot and pregnant again. There was cardboard over the windows of the shack. There was no uncontaminated water in the area and empty cardboard cases of state government plastic bottles were stacked up in the shade against the crumbling porch, shaped into a doghouse, a long, twitching snout poked out.

She took the long way back, looping dirt roads through some of the most beautiful country she could imagine. She’d been told Canada to the north was even more stunning, but she couldn’t imagine that. At the lift of a rise, she stopped the Expedition in the middle of the road and stared sadly down into a river where a creek bled effluent that looked like noxious green tea, now that the lumber mill up the other side, out of sight, was back in operation. A sign on the mill’s office said WO/NR. Ostensibly, it meant Work Office, Northern Initiative. In reality it meant Whites Only, No Injuns. The sawmill workers were tough but they found their own places to water themselves after a shift; the grim ramshackle bar in town was a little too edgy for them, so they drove thirty miles the other way and Djuna Brown’s guys had had to yank a lot of wrecks off the road and pry bodies out of windshields.

Above the feeder creek the water was pristine and thick with beautiful silver fish. Below, in the morning sun, it was fouled with fish with bulging eyes gasping on their sides.

But Ray would love it here, she thought, slipping the truck into gear. He’d be a mysterious striding ghost, climbing the folds of the hills and sinking into the shadows of the valleys, an easel over his shoulder and his clutch of paintbrushes and charcoal sticks in a hip holster. She imagined him talking to himself. Back when they were partners down in the city looking for the X-men, the traffickers who sold party drugs, she remembered him driving the bosses nuts with his rambling soliloquies. The Natives wouldn’t bother him because they recognized a slightly crazy soul, the spiritual worth of it.

They’d planned, after they got fired for thoroughly fucking up the X-men case, to take what buyouts they could negotiate and head to Paris, where he’d paint and she’d … well, she was sure she’d find some creative muscle to exercise. She didn’t see herself as an artist’s moll, stretching his canvases and darning his old denim shirts. But Ray loved his city streets, the young chargers for whom he felt responsible, strange for a doorstep baby who’d been raised in the grim cycle of state foster homes where the only loyalty was to survival. And they never got fired anyway. Ray took some bullets and closed it down for the shooter, a psycho ex-city cop, and Djuna Brown became a hero, crossing the thickest of lines and leaving a fat pervert dead in the dirt, a killer drug network broken, and a kidnapped girl rescued. A movie production company had flown her out to Los Angeles but she was too modest about her exploits to fit their dramatic needs, although a mannish script assistant swore true West Coast love for Djuna Brown’s little red slippers.

Two miles outside town she passed a trio of Native men walking along the highway, each carrying a long tube of rolled newspaper with thick moss poking out the ends. They turned at the distinctive sound of the Expedition engine and for a moment they showed fear, ready to head into the bush. Then they recognized her and nodded, and she slowed and offered rides. One, a slim man with a potbelly, declined politely. They didn’t have fishing rods or poles; from one man’s vest pocket she could see a length of fishing line looping out. The edges of the man’s hands had deep scars where the tackle lines had been grooving for decades, hand over hand to retrieve the fish. They all remained in easy silence for a few moments, then one of the men, she couldn’t tell which one because no one’s lips moved, made the perfect caw of a raven. She laughed, slipped into gear, and eased the truck away.

The raven’s call kept her smiling the rest of the way into town.

She’d been invited to a sweat lodge after she first