ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

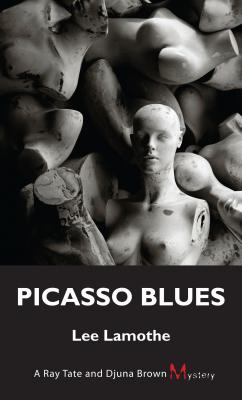

Picasso Blues. Lee Lamothe

Читать онлайн.Название Picasso Blues

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781554889679

Автор произведения Lee Lamothe

Жанр Ужасы и Мистика

Серия A Ray Tate and Djuna Brown Mystery

Издательство Ingram

He’d almost completely covered her with a kicking of leaves and stones and twigs. There’d been a rage in him as if he were kicking her entire existence off the surface of his planet.

Her left thigh was suddenly shot with feeling and she sighed happily at the pain, that she wasn’t totally paralyzed. A girl in high school had fallen only a very short distance off a root shed and became paraplegic. Her classmates explored in that morbid but human indulgence how they would handle being in a wheelchair for life. Some said they’d kill themselves. She herself had reserved judgement. In a wheelchair she could still operate her camera off a tripod of sticks, could direct her actors, could edit her video. A quadriplegic, now that was another set of problems she’d have to deal with if it came to that. She’d seen quadriplegics operate their motorized chairs by blowing into a tube. She could do that. A tube for panning, a tube for zooming, a tube for dissolve. All was doable, if you didn’t surrender.

She believed. God had repainted black sky blue for her, had populated it with those beautiful noisy birds to make her senses jump.

She believed. God had planted the seed that grew the tree that was butchered into timber and fashioned into a boat that had a hull that groaned and creaked nearby for her to hear.

She believed. God had made the clouds that made the rain that made the ice that melted and made the river that she could smell.

She believed God had let her keep this single lens in her face and let life pan itself across it so that she could record it for something.

And he’d created Horace, as if only to have him save her. She wondered if the man had taken Horace away with him. God wouldn’t do all that unless there was a purpose to the recording of it.

I’m going to live, she told herself.

She closed her eye and died.

But then, with the day alight and alive again, she heard a faraway voice calling, “Hey, Picasso. Yo. You got a reason for being here, Pablo?”

Chapter 1

The city was besieged.

An invisible and sinister mist had ridden in on a vicious breeze. The source of the deadly fog was the elusive Patient Zero, suspected to be an illegal migrant from China, a night horse spewing disease and spraying phlegm in a fifty-dollar dinghy, run across from Canada by a snakehead. At first no one had cared much: it was a vicious flu bug that seemed to only be attracted to Asians. But when the bug jumped races and whites, young and old, were infected, there were beatings and riots and arsons in East Chinatown. The Volunteers, formerly mere ad-hoc bands of crackpot racists, suddenly became prominent, more organized. They had a visible and public focus. A crude leadership emerged, and they manned the city airport, looking for international transfer passengers on flights from Chicago or Detroit. Night patrols ran up and down the waterway at the top of the city.

You could catch the bug by not washing your hands, or it was conducted through intimate contact, or it was in the ethnic foods, or it had an indefinite shelf life on banisters, telephone receivers, elevator buttons, or it was airborne and it gathered in pockets of clear vapour throughout the city, waiting to practise osmosis on hapless passersby. The conflicting information made a city of paranoia, of surgical masks and latex gloves and soap dispensers. People shook hands by touching elbows. Husbands and wives kissed each other near the ear.

The cops, who had to work in all kinds of medical weather, were hit hard. The few remaining moustachioed gunslingers from the robbery squad were twitchy. They cruised the downtown financial sector in heavily weaponed bank cars. Folks wearing masks on the streets triggered inside the gunslingers a genetic urge that they struggled to master. Except for Halloween, and that was iffy in some neighbourhoods, running the streets in a mask made you a magnet for a hollow-point. The gunslingers fought to control their tingling fingertips. Their frontier moustaches twitched in frustration.

The hammers of the Homicide Squad were almost wiped out; the bug had hit them hard in their dog-eyed wanders through the homes of murder victims and their constant presence in the dank halls of the stone courthouse. The hammers were reduced to chalking-and-walking or bagging-and-tagging, escorting corpses to the morgue where they told the fluorescent bleached clerks: You better stack ’em way back on the meat rack, Jack, ’cause I might come back in the black sack.

There was mindless violence. An unmasked Chinaman coughed in an elevator; he was stomped by fellow passengers. City buses became segregated: there were routes where all the passengers were Asian. Before boarding, non-Asian riders peered through windows to make sure they weren’t embarking on the Fuzhou Express. There were luggar bandits at work: crews of Asian kids who slipped out of East Chinatown and shook down the city, threatening to spit toxic phlegm onto pedestrians if they didn’t drop their wallets. Dim sum restaurants were bereft of clientele; the cart ladies had gone back to hoeing vegetables for street stands that nobody visited. In the subterranean massage parlours of Chinatown, the ladies danced naked except for their masks. Dreamy hand jobs came back into vogue for the lovelorn.

It was a humid dog day of summer and the bug breathed out a sigh, and a man in a black Chevy Blazer, his feet jammed into the detritus of around-the-clock surveillance, breathed it in.

Their skinner lived in a small brown post-war bungalow with an unhealthy undulating lawn and a sprinkler system that had gone on automatically an hour earlier. The house had grimy-looking beige curtains. A bouquet of flyers and envelopes poked up out of the black tin mailbox.

The spin team hadn’t seen their skinner all day. He was clearly inside: early lights had gone on; a shadow moved from room to room. When children passed by the house on their way to school, a curtain cracked at the corner of the bay window. After the children had passed and the school bell a block away rang, the curtain twitched shut and the house went still. At four o’clock when the last knapsack-laden little potential victim had trudged past the house safely, the spin team would move on to their next spot-hit assignment.

“Maybe he snucked out,” the wheelman said for the fourth time. “He gave himself his morning rub-and-tug at the window. It didn’t satisfy, and he went out the back, around the block, and grabbed one of the kiddies up.”

For the fourth time, the shotgun said, “Do I look like I give a fuck?” He rubbed his lower abdomen. “He could be ramping up his hard-on in the gym locker room, all we know, showing the kiddies what it looks like when it gets happy and spitting.” He made a belch, forcing it. “Ah, fuck.” He belched again. “Two guys doing a spin? What kind of fucking detail is this?” He shifted in his seat and pressed his hand to his diaphragm. “Geez, my guts.” He moaned. “Ahhh, fuck.” His stomach rumbled audibly. The air in the car took on a brown aura. “Donnie, I just shit my pants …” He wobbled as if he’d lost his gravity, looking like he wanted to cry from humiliation but instead suddenly convulsed, jackknifing his face hard into the dashboard. His nose spouted blood. His knees jerked up into the racked shotgun under the dash. “Ahhhh fuck, yack.” He began vomiting spasmodically and continuously onto the jumbled mess of camera equipment, clipboards, crushed tin cans, and coffee cups at his feet.

The wheelman, without pause, locked his breath and stumbled from the vehicle. He said: “Fuck, Stanley, fuck.” He pulled a white surgical mask from the back pocket of his blue jeans and clamped it to his lower face with one hand while with his other he groped at his belt for his rover and yelled, “Ten Thirty-Fucking-Three.”

Just before close of business on the day after Stanley the spinner blew his stomach all over the Chevy Blazer, the skipper of the Zombies received a rare telephone call at the Intelligence Bureau from a deputy chief at the Jank Center of Public Safety: “Cops are puking in Technicolor all over town,” a clipped voice twisted at him. “The State’s sending some troops. Meanwhile, dig up your bodies, we’re