ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

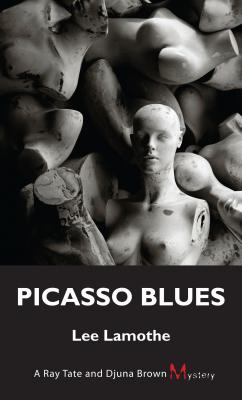

Picasso Blues. Lee Lamothe

Читать онлайн.Название Picasso Blues

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781554889679

Автор произведения Lee Lamothe

Жанр Ужасы и Мистика

Серия A Ray Tate and Djuna Brown Mystery

Издательство Ingram

“You’re a bit of a junkyard dog, Ray,” Djuna Brown had said after she got her stripes and visited him, convalescing in his apartment, a tube in his hip and a wad of gauzing on his ear. “You look like that little guy in the cartoon after the blunderbuss went off.”

He saw she was dodging something, that her smile and teasing eyes were a mask. “So,” he’d said, feeling bleak and hopeless, knowing. “Paris?”

Beatnik life in Paris is what they’d promised each other.

She looked very sad. “No can do, buckaroo.”

They’d just finished the X-men case. He hadn’t done much, just went from place to place with her and somehow they’d stumbled on the chemistry set used by a degenerate businessman and a psycho killer. She whacked the degenerate and the tactical guys took down the psycho. Ray Tate hadn’t even been there, because a jealous lesbian ex-cop who had a jones for Djuna Brown had come by his apartment and opened up on him. He left her dead in the doorway and afterwards he lay on his floor, waiting to die, glad, looking at the fresh pockmarks in the plaster ceiling, that he hadn’t wasted money painting the place.

Djuna Brown had come to his apartment to tell him she was going back to her precious Indian country, to her shacks and shanties and Saturday night bust-outs. Originally she’d been assigned up there as a punishment because she was thought to be gay; now it was her reward for being a hero. Bodies hanging from rafters in despair; families wiped out by accident and suicide, by murder and the simple surrender of life. But there was also the fish wrapped in damp moss, the bloody hunks of deer or bear during the season, presented to her with prideful love and meticulous cooking tips. Teaching girls about their periods and pregnancy and boys about respect and responsibility. She told him all this so he’d understand her duty.

“This thing we have, Ray, it’s portable, you know? You could come up there.” They’d been laying on his futon looking up at the splotches in the ceiling where Ray Tate’s daughter and her friends had re-plastered the bullet holes.

But just as Djuna Brown couldn’t abandon her sad tribe, he couldn’t abandon his cops, young chargers burst into a world with no supervisors, no one to teach them how to police, when to police. He imagined them dead on the road because no one told them not to lean on the cars they pulled over, not to disrespect a man in front of his family, to take a subtle step back, deal out some breathing room, to freeze a situation to give everyone a chance to get perspective, to get back to being human.

So she went to Indian country and he stayed in his streets. He didn’t call unless he was drunk; she didn’t call unless she had the deep blues. There was a lot of silence over the wires. He called less and less and so did she. It hurt too much. Then he just stopped, afraid that she’d find the combination of words and promises and dreams that would make him walk away from the city.

Once, after a bad day followed by a lonely night, he decided he’d had enough, he couldn’t carry the water, didn’t even want to. With a stub of charcoal, he parsed his early pension and his savings and the monthly payout to his ex-wife. He packed his car with clothes and paints and drove to an Amoco where he tanked up, meticulously cleaned the windshield, and bought a bag of snacks for the long drive north. He didn’t call to tell her he was coming. He knew himself too well and knew he might fold at the last moment, before the last off-ramp to Indian country.

Just before he hit the Interstate north, his daydreams of a life with a cocoa midget cop in the boonies evaporated in the slipstream of four screaming cruisers charging past him. He got in line, flashing his high beams, leaning his horn. On the Eight he climbed from his car, hung his badge around his neck, and waded through cruiser gridlock.

On the sidewalk a young charger with a bullet hole in his jaw lay grunting, comforted by his crying partner, a sturdily built young woman who looked barely out of her teens. Between them they seemed to have about fifteen minutes on the job. Ray Tate took control of the stage and set a perimeter. He ignored the three chargers who had the shooter down behind a dark blue van, stomping him.

The shooter screamed, “Why’d he let me do it, huh?” He gasped as he absorbed some boots. “What kinda fuckin’ cop is that, huh?”

“He ain’t wrong, Ray,” a charger told him, catching his breath between bouts of the boots. “Kid was on the job about a week. He came up with a smile and hi-how-are-ya. So of course the guy shot him. He’d’a shot the escort too, except his piece jammed.” He rubbed his hand on his slick face. “You want in, get a few licks for the team?”

“Another minute, Bobby, then I take him out of here. I’ll need a car for prisoner transport.”

“Ambo on the way, don’t sweat it, Ray.”

“Another minute, Bobby, I mean it, man, then you chain him up and read him the poem. You don’t want to lose this in court.”

Ray Tate carried the weight of dead bodies and the charger had to nod.

He drove home and unpacked his car. On his futon he twisted, not with the gunshot face of the charger in his mind, but the face of the downed cop’s partner who’d repeated over and over: “What could I do?”

She had the gaunt brown face of Djuna Brown, the stressed old Djuna who’d come to the city as a basket case and left as a hero cop.

He thought about her all the time and he dwelled in the imagined grimy architecture of romantic Paris, sketching or painting her in the late nights, and in really bad times of temptation he unplugged the telephone and locked it in the trunk of his car.

But he never tried to leave again. A doorstep baby of the state who’d lived in the revolving doors of foster homes, the blue tribe was the only family, dysfunctional and protective, brutal and tender, that he’d ever had.

The bell tower above the courthouse sounded eleven-thirty. There was no sign of the fingerman from homicide. The gangbangers and sad lawyers and striding cops had abandoned the wide stone steps to the pigeons. Ray Tate gathered his raid jacket, rolled it inside out under his arm and went inside to the security kiosk. Subtly, he palmed his badge at the masked guards and went around the metal detectors. A masked court officer pointed wordlessly at the disinfectant soap dispenser mounted on a pillar. There were six pay phones studded to the wall in the gallery and each was in use, by people who showed no sign of hanging up any time soon. He headed for the stairs.

The noisy, crowded basement corridor was a moist lung. The bug, he thought, would like it here, in the humidity and sweat. Outside first-appearance court, he leaned beside the defaced docket thumb-tacked to the wall, waiting for court security to unlock the room. Most of the people churning in the hallway were relatives of suspects gathered up in a series of overnight crack raids. Most of them were black, and even with their masks on he recognized a few dealers from the Hauser Projects by the Ws shaved into their hair. There were only a couple of lawyers on hand, so the overnight arrestees would let the duty counsel sort their cases out and listlessly pitch for low bail. A man stared at Ray Tate briefly, then away, and then back, trying to penetrate the greying beard and combed-back long greasy hair. Ray Tate popped a kink from his spine, yawned, loudly sucked snot back into his throat, scratched his crotch, and slouched along the hall reading dockets, keeping an eye out for any well-dressed cop who looked like a hammer from Homicide.

When he checked up in the gallery again, the phones were still occupied. Ray Tate went outside and stood in the sunshine. A young blonde woman wearing a white mask climbed out of a taxi at the curb and crossed past the cenotaph, giving the hacking bum a wide berth. She peered at Ray Tate. “Sergeant Tate?” She kept her hands behind her back in case he wanted to shake. She stood eight feet away. She had pretty eyes and plucked, arcing eyebrows. Her voice was a little muffled. “Ray Tate?”

“I’m Tate.” He started to drift but then disciplined himself, picturing her under the mask with a harelip, yellow teeth, and the firm shadow of moustache.

“I was told to tell you your target won’t be coming out. He was taken from