ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

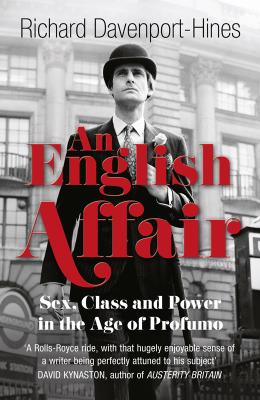

An English Affair: Sex, Class and Power in the Age of Profumo. Richard Davenport-Hines

Читать онлайн.Название An English Affair: Sex, Class and Power in the Age of Profumo

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780007435869

Автор произведения Richard Davenport-Hines

Жанр Социология

Издательство HarperCollins

In 1924, Macmillan captured a difficult industrial constituency, Stockton-on-Tees, by unusual methods. He insisted that his local supporters contribute to election expenses, reorganised the local association along democratic lines, declined the help (or handicap) of speakers sent by the central party organisation in London, and left unopened the parcels of official propaganda. His distress at the unemployment and privation of north-east England made him a rebel against economic orthodoxies. In 1927 he and three other young MPs who were styled ‘Tory Democrats’ issued a milk-and-water Keynesian booklet entitled Industry and the State. ‘A Tory Democrat,’ sneered a socialist professor, ‘means you give blankets to the poor if they agree not to ask for eiderdowns.’ Nevertheless, Aldous Huxley found much sense in Macmillan’s 1931 publication Reconstruction: A Plea for National Unity, and told T. S. Eliot: ‘I’m glad the young conservatives are waking up.’5

Together with Sir Cuthbert Headlam, Macmillan formed the ‘Northern Group’ of Tory MPs lobbying on behalf of the region. ‘He is a curiously self-centred man, and strangely shy and prickly – and yet the more I see of him the more I like him,’ Headlam noted after a talk in 1934. Although Headlam advised him to continue pushing progressive ideas, but to stop speaking and voting against the government, Macmillan did not restrain his dissent. He affronted fellow Tories by telling a newspaper interviewer in 1936 that ‘a party dominated by second-class brewers and company promoters – a casino capitalism – is not likely to represent anyone but itself’. That year he was the only backbencher to resign the party whip when Baldwin’s government lifted sanctions which had been imposed on Mussolini’s Italy after the invasion of Abyssinia. Although he rejoined the party after Neville Chamberlain became Prime Minister in 1937, he risked de-selection as a Conservative candidate by continuing opposition to appeasement of dictators. In 1938 he wrote a Keynesian treatise entitled The Middle Way, which indicted Conservative economics as callous and complacent, and argued for more consensual, corporatist, expansionist economics. The London Stock Exchange, he suggested, should be replaced by a National Investment Board. This was not the rebellion of a showy, self-seeking mutineer, but the dissent of a man who obstinately, perseveringly, worked out new lines for himself.6

In 1940, when Churchill became Prime Minister, he chose Macmillan as Parliamentary Under Secretary at the Ministry of Supply. About a month after this humdrum appointment, Headlam sat beside Macmillan at the long table where members dine together at the Beefsteak Club. ‘He is very much the Minister nowadays, but says that he has arrived too late to rise very high,’ Headlam noted. ‘I can see no reason (except his own personality) for his not getting on – even to the top of the tree – but he is his own worst enemy: he is too self-centred, too obviously cleverer than the rest of us.’ Shortly after this Beefsteak evening, Macmillan was motoring in a car with his private secretary, John Wyndham. After desultory conversation, Macmillan fell into brooding silence. Then suddenly, with intense emphasis, but as if talking to himself, he exclaimed: ‘I know I can do it.’7

These glimpses of Macmillan at forty-six – delighted to have reached office, but equivocal about his prospects – are telling. He felt his aptitude for power, but sensed he must disguise his clever ambition. His confidences to Headlam, his exclamation before his most trusted aide Wyndham, prefigure him briefing journalists in 1956 that his political career was over as he poised himself to take supreme control.

At the end of 1942 Churchill offered the post of ‘Minister Resident at Allied Forces Headquarters in Algiers’ to Macmillan, his second-best candidate, whom he had recently described as ‘unstable’. Macmillan accepted without a moment’s havering. It proved to be a hard job, unrewarding in outward prestige, but he won praise from those who knew of his behind-the-scenes adroitness. With both the American and Free French representatives he was direct in his approach but insinuating in his ideas. During the closing phase of the war, Macmillan headed the Allied Control Commission in Italy, becoming, said Wyndham, ‘Britain’s Viceroy of the Mediterranean by stealth’.8

By the war’s close Macmillan had been married for a quarter of a century. He had met Lady Dorothy Cavendish when he was serving as aide-de-camp to her father, the Duke of Devonshire, who was then Governor-General of Canada. They married – she aged nineteen, he twenty-six – at St Margaret’s, Westminster in 1920. The bride’s side of the church was filled with hereditary grandees: Devonshires, Salisburys, Lansdownes; the groom’s with Macmillan authors, including Thomas Hardy, who signed as one of the witnesses. The young couple took a London house, at 14 Chester Square, on Pimlico’s frontier with Belgravia. After 1926 they also shared Birch Grove, a large house newly built in Sussex under the directions of his mother. The marriage deteriorated after 1926, as Dorothy Macmillan chafed under her mother-in-law’s meddling intimidation.

One of the Tory Democrats to whom Macmillan was closest in the 1920s was Robert Boothby, a dashing young MP with an unruly mop of black hair and bombastic style of speechifying. Dorothy Macmillan was attracted to him when they met during a shooting and golfing holiday in Scotland in 1928: during a second holiday after Macmillan’s defeat in the general election of 1929, she squeezed Boothby’s hands meaningfully while they were on the moors. Their affair was consummated during a house party with her Lansdowne cousins at Bowood. Photographs of the pair, taken at Gleneagles, show her as clear-skinned and strong-limbed, with prominent eyebrows and chin, a saucy grin, and the air of an undergraduate. Of the two lovers, Dorothy Macmillan had the dominant temperament.

Boothby was intelligent, but wayward in his habits and ductile in his feelings. ‘A fighter with delicate nerves,’ Harold Nicolson called him in 1936. Boothby had a look of manly vigour, with a boisterous style, and a reputation as a coureur des femmes. Nevertheless, he enjoyed being chased by men during his trips to Weimar Germany, and supposedly enjoyed frottage with fit, ordinary-looking, emotionally straightforward youths. Homosexuality, however, drove public men to suicide or exile in the 1920s, and stalled careers; indeed it was a preoccupation of policemen and blackmailers until partially decriminalised in 1967. ‘I detected the danger and sheered away from it,’ Boothby later wrote.9

Dorothy and Harold Macmillan had one son and three daughters. She fostered the untruth that their youngest daughter Sarah, born in 1930, had been fathered by Boothby, in the hope of provoking her husband to agree to a divorce. Macmillan did not yield to this wish. A solicitor whom he consulted warned that divorce would be an obstacle to receiving ministerial office, and might make Cabinet rank impossible. It might even require him to resign his parliamentary seat (as happened in 1944 when Henry Hunloke MP was in the process of divorce from Dorothy’s sister Anne, and seemed likely for a time in 1949 when James Stuart MP, married to another sister, was cited in a divorce). There would have been outcry at Birch Grove, too. His brother Arthur had been ostracised by their mother for marrying a divorcee in 1931, despite consulting the Bishop of London before proceeding with the ceremony.

Until the divorce reforms of 1969, it was necessary for one of the married partners to be judged ‘guilty’ of adultery or marital cruelty before a divorce could be granted. It was considered deplorable, except in flagrant scandals, for a man to attack his wife’s reputation by naming her as the guilty party. Instead, even if the wife had an established lover, the husband was expected to provide evidence of guilt, by such ruses as hiring a woman to accompany him to a Brighton hotel, signing the guestbook ostentatiously, sitting up all night with her playing cards, but having sworn evidence from hotel staff or private detectives that they had spent the night together. Macmillan, who had been neither adulterous nor cruel to his wife, refused to collude in fabricating evidence of marital guilt: still less was he willing to sue her for divorce, and cite Boothby as co-respondent. ‘In the break-up of a marriage,’ Anthony Powell wrote of the 1930s, ‘the world inclines