ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

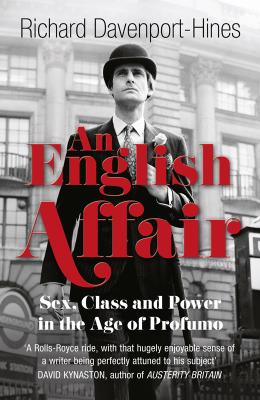

An English Affair: Sex, Class and Power in the Age of Profumo. Richard Davenport-Hines

Читать онлайн.Название An English Affair: Sex, Class and Power in the Age of Profumo

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780007435869

Автор произведения Richard Davenport-Hines

Жанр Социология

Издательство HarperCollins

The kinship created by war was richly evoked in a film, The League of Gentlemen, released in 1960. A group of ex-army officers, shunning the women who have humiliated, scolded, manipulated and bored them, unite in masculine camaraderie and military discipline to rob a million pounds from a City bank. The common fund of memories was drawn on in Granada Television’s comedy series The Army Game, which gradually became dominated by Bill Fraser playing Sergeant Major Claude Snudge and Alfie Bass playing his stooge, the sly, imbecilic Bootsie. From the autumn of 1960 (running until 1964) Granada screened a spin-off of The Army Game called Bootsie and Snudge. An average of 17 million people watched its Friday night slot during April and May 1961. Snudge had become the porter of a Pall Mall club with Bootsie as his dogsbody. They carried, wrote a critic, ‘the ambivalent, equivocal and sometimes almost flagrantly – though, I suppose, always sublimated – homosexual relationship between these two monsters as far as possible, exploiting all conceivable nuances’.24

Wartime affinities were enduring. Attlee and Macmillan were the only Prime Ministers in three centuries to have been seriously wounded in battle. The experience imbued them with compassion and fortitude. Young officers in the trenches, living at close quarters with the men of their platoon, so Macmillan wrote in old age, ‘learnt for the first time how to understand, talk with, and feel at home with a whole class of men with whom we could not have come into contact in any other way’. His war record helped him in the Tory leadership, for until the 1960s to have had ‘a good war’, and especially to have been wounded, rightly commanded respect. Macmillan’s limp proved his patriotism. He despised those who (for whatever reason) had avoided active service. ‘The trouble with Gaitskell is that he has never seen troops under fire,’ he told a dining club of Tory MPs who had been elected in 1959. Three months into Wilson’s premiership in 1965 he commented: ‘It seems strange that a man who claimed exemption (as a civil servant or the like) at twenty-three and took no part in the six years war, can be PM. We certainly are a forgiving people.’25

This was an era when people still saluted as they passed the Cenotaph in Whitehall. ‘Rank insubordination’ was a phrase that some laughed at, and others recognised had a valuable meaning. A question of precedence arose when Profumo’s wartime senior commander Field Marshal Earl Alexander of Tunis dined at Cliveden in 1962. The moment came for the men to leave the dining room to join the ladies. ‘By age and distinction,’ recorded a fellow guest, ‘there was every reason for him to go out first, but he didn’t immediately do so, since as an earl his rank was below that of the Marquess of Zetland’s. While he hesitated to go, there was a respectful silence, everyone looking towards him with quiet admiration and, by a slight inclination of the head, inviting him to lead the way. A hardly visible expression of pleased assent passed over his face. He went out as it were imperceptibly, as if it just happened that he went out first.’ As late as 1978, Lord Denning came within an ace of being disbarred from appointment as Deputy Lieutenant of Hampshire on the grounds that his military service in 1917–19 had been spent in the ranks.26

Profumo’s son David, who was born in 1955, recalled seeing war-wounded fathers of his school friends – men wearing eyepatches, those who kept an empty sleeve pinned to their jacket, the father whose face was gruesomely disfigured despite all the skill of plastic surgeons. Public men especially needed to show that they had had ‘a good war’. Jack Profumo had fought in the battle of Tunis and the invasion of Sicily; as the youngest brigadier in the British Army he had been second-in-command of the British Military Mission in Tokyo. He was still on the military reserve in 1963. The Labour candidate who stood against him at Stratford-on-Avon in 1950–51 had been awarded the Military Cross after the Battle of the Somme in 1916; his Labour opponent in 1955 had served in the Royal Navy; while Joe Stretton, the fifty-year-old Labour candidate for Stratford-on-Avon in the 1959 general election, a Co-op worker and councillor in Rugby, had war service with the Royal Army Ordnance Corps in Italy and Austria.

‘Funny how the war was a historical watershed,’ mused the Labour MP Wilfred Fienburgh in 1959. ‘Every date, every age, had to be translated into terms of how many years before or after the war.’ When a man over forty saw a pretty young woman, his calculations were framed by the war: that she was just born when it started, suckling when he paraded for his first rifle drill, toddling and talking when his fighting started, and entering primary school when he was de-mobbed.27 One wonders if Profumo had comparable thoughts about Christine Keeler, who was a swaddled infant when he was fighting in Italy and not yet at school when he first met his wife.

Profumo’s great task as Macmillan’s Secretary of State for War was to manage the abolition of National Service, and to return the army to a body of professional volunteers. His political adversary, Colonel George Wigg, jibed that this required him to massage the army’s recruitment figures so as to prevent any necessity of reviving conscription. Under the terms of the National Service Act of 1947, all eighteen-year-old men were obliged to serve in the armed forces for eighteen months (raised to two years after the outbreak of the Korean War). More than 2 million youths were called up (6,000 every fortnight): the army took over a million; there were thirty-three soldiers, or twelve airmen, for every sailor. After discharge, conscripts remained on the reserve force for another four years, and liable to recall in the event of an emergency. Although the abolition of National Service was announced in 1957, conscription continued until 1960, and the last conscripts were not released until 1963. Some suspected that the government would be obliged to introduce selective service by ballot, which opponents denounced as tantamount to crimping during the American Civil War. Others regretted the retreat from notions of individual obligations and service to the state.

By 1963 there had never been so many ex-soldiers and ex-sailors in British history. Many people respond well to being drilled: in England, millions of people were respectful of authority, conformist, glad of regular pay and communal amusements. ‘Only a fool could resent two years National Service as a waste of time,’ wrote the art connoisseur Brian Sewell, who was conscripted in 1952. ‘Bullying, brutality, intimidation and fear were among its training tools with raw recruits, victimisation too, but even these had their educative purposes, and were the stimulus of resources of resilience that had not been tapped before.’ Many young men, unlike Sewell, seethed at the regimentation and sergeant majors’ bullying. With two by-elections pending at Colne Valley and Rotherham in 1963, nearly 700 servicemen tried to escape from the armed services by standing as parliamentary candidates. The government reacted by appointing a panel, chaired by David Karmel QC, to winnow the men. Only twenty-three of the 700 applied to Karmel for interview. A single one was approved: ‘Melvyn Ellingham, twenty-four-year-old REME sergeant, yesterday became the first Army Game by-election candidate to win his freedom.’ He had joined the army aged fifteen, and had two years still to serve as a £14 8s a week electronics technician. ‘I’m for the Bomb,’ he told the Daily Express, but ‘against the Common Market. I think a united Europe would only aggravate world tension.’28

The psychic air of mid-twentieth-century England was thick with bad memories. Pat Jalland, in her history of English grief in a century of world wars, quotes from the memoir of J. S. Lucas, a private in the Queen’s Royal Regiment who, like Profumo, served in the gruelling campaigns in Italy. Before the action at Faenza in 1944, when Lucas was aged twenty-one, he was reunited with his friend Doug, beside whom he had fought in Tunisia. Doug had just asked him for a smoke when a mine exploded. ‘My hand was still opening the tin of cigarettes,’ wrote Lucas, ‘and even as I ran to where he lay, my mind refused to accept the fact of his death. One moment tall, a bit skinny, wickedly satirical, and now – nothing – only a body with a mass of cuts and abrasions and a patch of dirt on his forehead … I felt sure that some part of his soul must be hovering about. But he had gone – forever … between asking for a fag and getting one.’ That night at Faenza, in freezing cold, after heavy losses from shelling, the remnants of Lucas’s company took shelter, but he was too hungry and agitated for sleep. ‘Before my eyes there passed, in review, a