ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

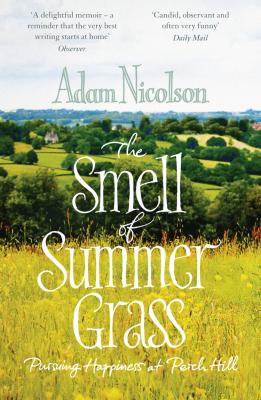

Smell of Summer Grass: Pursuing Happiness at Perch Hill. Adam Nicolson

Читать онлайн.Название Smell of Summer Grass: Pursuing Happiness at Perch Hill

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780007335589

Автор произведения Adam Nicolson

Жанр Биографии и Мемуары

Издательство HarperCollins

The chickens we had foolishly acquired roamed delightedly among the old-food-encrusted earthwork-play zone where we let them out every day. They redistributed the mess. None of it ever seemed to disappear.

I had come to hate our chickens. They lurked about in the same murky province as unwritten thank-you letters and work that’s late, the guilt zone you’d rather didn’t exist. One is meant to love chickens, I know: their fluffy puffball existence, the warm rounded sound of their voices, a slow chortling, the aural equivalent of new-laid eggs, and of course the eggs themselves, gathered as the first of the morning sun breaks into the hen house and the dear loving mothers that have created them cluster around your feet for their morning scatter of corn.

Well, I hated them. Before the chickens arrived, I loved them. I sweated for days, building their run with six-foot-high netting, buried at the base so that the fox couldn’t dig in to get them, with additional electric fencing just outside the main wire as another fox deterrent. I made a charming wooden, weather-boarded house for them, the inside of which I fitted out as though for a page in Country Living. There were some elegant nesting boxes, with balconies outside them so that the hens could walk without discomfort to their accouchements, ramps towards those balconies from the deeply straw-bedded ground, a row of roosting poles so that at night they could feel they were safe in the branches of the forest trees which the Ur-memories of their origins in the forests of south-east Asia required for peace of mind.

When it was finished, I sat down on the rich-smelling barley straw and smoked a cigarette, thinking that this was the sort of world I would like to inhabit.

We should have left it at that, but we didn’t. We actually bought some chickens. And a cockerel. He came in a potato sack and when I tipped him out on to the grass and dandelions of the new run, he stood there, blinking a little, surrounded by his harem, and I couldn’t believe we had acquired for £8 such a shockingly beautiful creature. He was a Maran, his white body feathers flecked black in bold, slight marks as if made with the brush of a Japanese painter. His eye was bright and his comb and long wattles the deep dark red of Venetian glass. He seemed huge, standing a good 2 feet high, and this fabulous, porcelain-figure colouring made a superb and alien presence in our brick and weatherboarded yard. His chickens, which he cornered and had with a ruthlessness and vigour we could only admire, were dumpy little brown English bundles next to him, heavy-laying Warrens, dish-mops to his Byron. For two days after his ignominious sack-borne arrival, he remained quiet but then he began to crow, his cry disturbingly loud if you were near by but, like the bagpipes, beautiful when heard in the distance, down in the wood or with the sheep two fields away.

Within a couple of weeks it was going wrong. I was collecting eggs with my son Ben, who was seven. It was early evening and the chickens were still out. We didn’t realize it but the cock was already in the house and with only the warning of a couple of pecks on my feet, which I didn’t recognize for what they were, he suddenly attacked Ben, banging and flapping against his trouser legs in a terrifying explosion of feathers and movement and noise. Ben and I scrambled out of the hen house, him in tears, me shaken.

It worsened over the next few weeks. We were all attacked in turn until one Sunday morning found the entire family cowering behind the glass of the back door, checking to see if Terminator, or Killer Cock as he was also called, was out on the prowl. He had come, I am sure, to sense our fear and was now certain of his place as Cock of the Walk. He had to go. Of course, there was no way I could bring myself to capture him and so we hired a professional to take him away. We thought there might be the most horrifying execution scene in a corner of the yard. What actually happened was a lesson in the psychology of dominance. Alf Hoad is a man with enormously hairy arms. He lives in the village and shoots deer. He was our chosen executioner. Alf arrived in his Land Rover, stepped out of it carrying a sack, walked up to the cock and put him in it. My manliness rating dropped like a stone. The children now look on Alf as something of a god. He took the cock away alive and used him as a guard dog to protect his pheasant chicks against foxes.

It was a relief when Killer went. We could walk about again outside without fear of a rake up the back of the legs, but, without their man, our ugly little brown chickens suffered a drop in status. I looked at them and saw only the slum conditions in which they lived – my fault, they didn’t have enough room – and their scrawny appearance – nature’s fault, as they were going through the moult – and I blamed them for both. They stopped laying with the days shortening, and so we didn’t even have any eggs. In fact, we were quite pleased about that because we had come to think eggs disgusting.

People, I now understood, had got the wrong idea about chickens: they are not the soft, burbly things they always appear to be in pictures and advertisements. They are utterly and profoundly manic. This whole short history had taught me an important lesson. There is something about the chicken which invites maltreatment. No one, I think, would ever have tolerated the idea of battery ducks, even if that were possible. People have caged billions of chickens in the most intolerable conditions because everything about them tells you that they have no soul. This is not to condone it, but it does perhaps explain it.

The chickens somehow made the winter worse, its awful unshaven stubbliness. The whole of Sussex looked as if it had been in bed with flu for a week. Its skin was ill and a sort of blackness had entered the picture, as if it had been over-inked. No modern descriptions of winter ever put this clodden, damp mulishness at the centre of things. People always talk about ice and frost and glitter and hardness and crispness and freshness and brightness and sparkle and brilliance and tingle. It’s all nonsense. England is at sea and has sea-weather, a mediated dampness. That winter it entered our souls.

In a sea of unglittery mud and damp prospects, with things unfinished, never unpacked or never started all round us, we huddled over our fires. Visiting friends were amazed at the mess. Our first year had come to an end. Was it, I still wondered silently, a mistake? Did we belong here? What were we doing here? Were we going to be happy here? Had we swapped one sort of unhappiness for another?

Why did we stay when so many others leave, just at this point? The euphoria, the bursting of energy from the bottle as it was first opened, had popped and fizzed and diminished and sunk, leaving only the still liquid in the glass. We were left with the plain fact. We had our work to do. I was writing for the Sunday Telegraph, columns about our life on the farm and others more generally about the politics of the early 1990s, the end of the Thatcher era, the John Major interval, the coming of New Labour, the political conferences, the disintegration of the Tory world, the expanding levels of hope that seemed to emanate from the Blair camp. I had a coffee cup emblazoned with the slogan, red on black, ‘New Labour, New Hope’. It has been through the dishwasher so often that the words are illegible now. I was writing profiles of the political leaders, spending two or three days ‘up close and personal’, as it said in the paper with Blair, Major and the Liberal leader Paddy Ashdown, while writing a book, my first for several years, on the restoration of Windsor Castle after its fire in 1992 for which I interviewed hundreds of consultants, architects, builders, members of the Royal Household, curtain makers, gilders, wood carvers. It was a busy, engaged time. Life was starting to fruit again.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или