ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

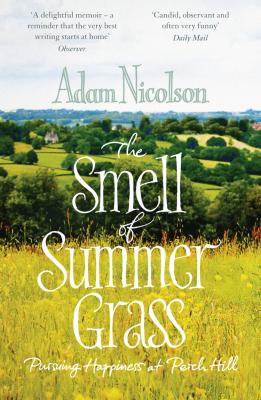

Smell of Summer Grass: Pursuing Happiness at Perch Hill. Adam Nicolson

Читать онлайн.Название Smell of Summer Grass: Pursuing Happiness at Perch Hill

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780007335589

Автор произведения Adam Nicolson

Жанр Биографии и Мемуары

Издательство HarperCollins

‘They aren’t. What’s wrong with the garden?’

‘It’s out of control.’

‘That,’ I told her, ‘is also what’s wrong with the fields.’

‘I’ve never heard anything so ridiculous. Fields don’t get out of control. That’s one of the good things about them. They just sit there perfectly in control for day after day.’ Gardens didn’t, apparently. Gardens were nature on speed. In fact, you could see them as hyperactive fields. They went mad if you didn’t look after them. Anyway the fields were not going to be photographed on Wednesday, were they?

This was true. Sarah had got a job as a junior doctor in the renal unit of the hospital in Brighton. She was sharing it with another young doctor but even half-time, in the days of famously long hours for junior doctors, it often required her to be there 40 hours a week. The hospital was about 45 minutes’ drive each way. Day after day, she had to leave early and return late, missing Rosie, feeling that she had come here to find a new life with us but that her work was taking her away to the point where our lives were hardly shared at all. Even when at home, she was too tired to take much pleasure in what we were doing, or where we had come to. It seemed absurd.

We decided together that she couldn’t go on. When she had been pregnant with Rosie and after she was born, Sarah, who is incapable of doing nothing, had taken time off and set up a florist’s business called Garlic & Sapphire with her university friend Lou Farman. As florists do, they had bought their flowers and foliage from wholesale merchants in Covent Garden market. This was fine, but it was not that easy to make any kind of living, and anyway it felt a little tertiary: selling flower arrangements to London clients from boxes of flowers bought at a market and almost entirely shipped in from industrial-scale producers in Holland. We could do better than that.

Sarah’s father, a classics don at King’s College, Cambridge, had also been a passionate botanist who with his own father had painted the entire British flora and was the co-author of the New Naturalist volume on mountain flowers. He had taken Sarah as a girl botanizing across bog, heath, mountain, meadow and moor in England, Scotland, Italy and Greece. She had drunk flowers in at his knee and from him had learned the science of flower reproduction and habitat. The Ravens had also made inspirationally beautiful gardens at their house near Cambridge (chalky) and around their holiday house on the west coast of Scotland (acid). So this much was clear: Sarah had gardens in her genes. She had to make a garden. Her life would not be complete unless she did.

We had made together a small and lovely garden in London with pebble paths and hazel hurdles and we had talked together about making it more productive. One day I happened to be sitting next to the publisher Frances Lincoln at a wedding party. ‘Do you know what you should publish?’ I said. ‘No,’ she said, a little wary. ‘A book called The Cutting Garden about growing flowers to be cut and brought inside the house.’ ‘Are you going to do it?’ she asked. No, I wasn’t, but I knew someone who could.

So this was already in our mind when we came to Perch Hill and it was obvious that when Sarah gave up her job as a doctor, to look after Rosie and to be with us at home, she should embark on making the cutting garden and writing the book. We wrote the proposal together, with plans, plant lists and seasonal successions, and sent it off to Frances, and soon enough it was commissioned. Perch Hill was about to take its first step to new productivity.

It was to be a highly and beautifully illustrated book whose working title at home anyway was The Expensive Garden. From time to time in various parts of the house I used to find half-scribbled lists on the back of invoices from garden centres spread across the south of England, working out exactly how much had been spent on dahlia tubers, brick paths, taking up the brick paths because they were in the wrong place, the new, correctly aligned brick paths, the hypocaust system for the first greenhouse, the automatically opening vent system for the second, the underground electric wiring for the heated cold frames (yes, heated cold frames), the woven hazel fencing to give the correct cheap, rustic cottage look (gratifyingly more expensive than any other garden fencing currently on the market) and the extra pyramid box trees needed before Wednesday.

The consignment of topiary was delivered, one day early that summer, by an articulated Volvo turbo-cooled truck, whose body stretched 80 feet down the lane – it had caused a slight traffic rumpus on the main road just outside Burwash, attempting to manoeuvre itself like a suppository into the entrance of the lane – and whose driver with a flourish drew aside the long curtain that ran the length of its flank, saying ‘There you are, instant gardening!’ He must have done it before.

The inside of the lorry was a sort of tableau illustrating ‘The Riches of Flora’. It contained enough topiary to re-equip the Villa Lante. Species ceanothus, or whatever they were, sported themselves decorously among the aluminium stanchions of the lorry. The rear section was the kind of over-elaborate rose and clematis love-seat-cum-gazebo you sometimes see on stage in As You Like It. Transferred to the perfectly unpretentious vegetable patch maintained by the Weekeses, the disgorged innards of the Volvo turned Perch Hill Farm, instantly, as the man said, into the sort of embowered house-and-garden most people might labour for 20 years to produce. A visitor the following week congratulated Sarah on what he called ‘its marvellous, patinated effect’. Some patina, I said, some cheque book.

At that stage, the advance on The Expensive Garden had covered about fifteen percent of the money spent on making it. If even a tenth of that amount had been spent on the farm we would already be one of the showpieces of southern England. ‘That point,’ Sarah was in the habit of saying, for reasons I have never yet got her to explain, ‘which you always make when we have people to supper, is totally inadmissible.’

But I was serious about the fields. I wanted the fields, which were beautiful in the large scale, to be perfect in detail too. I wanted to walk about in them and think, ‘Yes, this is right, this is how things should be. This is complete.’ That is not what I was thinking that summer. In fact, the more I got to know them, the more dissatisfied I became. Hence the 4 a.m. anxieties. The thistles were terrible. Some fields were so thick with thistles that my dear dog, the slightly fearful and profoundly loving Colonel Custard, refused to come for a walk in them. He stopped at the gate, sat down and put on the face which all dog-owners will recognize: ‘Me through that?’

In the early hours, I used to have a sort of internal debate about the fields. It came from an unresolved conflict in my own mind, which could be reduced to this question: was the farm a vastly enlarged garden or was it part of the natural world which happened to be ours for the time being? The idea that it might be a business which could earn us money had never been seriously entertained. We might choose to have sheep, cows, chickens, ducks and pigs wandering about on it, but only in the same way that Sarah might order another five mature tulip trees for a little quincunx she had in mind. I would have animals because they looked nice.

To the question of big garden or slice of nature, I veered between one answer and then the other. In part it was like a huge, low-intensity garden. We were here because it was heart-stoppingly beautiful and one of the things that made it beautiful was the interfolding of wood, hedge and field. If the distinctions between them became blurred then a great deal of the beauty would go. The fields must look like fields, shorn, bright and clean, and the woods must look like woods, fluffy, full and dense. Field and wood were, here anyway, the rice and curry of landscape aesthetics. Scurfy fields, as spotty as a week’s stubble on an unshaven chin, looked horrible, untended, a room in a mess.

There were other things to think of too. If we simply mowed the fields to keep them bright and green or, horror of horrors, sprayed off the docks and thistles, we would not be attending to other aspects of the grassland which of course are valuable in themselves. There were clumps of dyer’s greenweed here, whole spreads of the vetch here, called eggs and bacon and early purple orchids on the edges of the wood. Sprays would wreck all that and you had to allow those things