ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

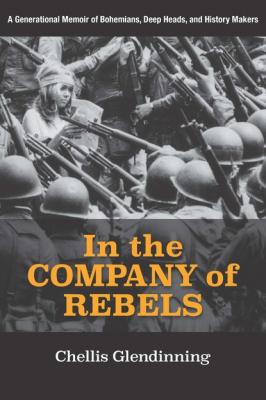

In the Company of Rebels. Chellis Glendinning

Читать онлайн.Название In the Company of Rebels

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781613320976

Автор произведения Chellis Glendinning

Издательство Ingram

At this point fate looked kindly upon Susan. She had been babysitting at the home of Gerry and Morton Dimondstein, sometimes staying with them several nights a week. After her father died, they became her legal guardians, and their influence shaped Susan’s life. They were bona fide Bohemians—he an artist known for his woodcuts in the tradition of Mexican Realism, she an arts educator. And they were ex-Communists. During the McCarthy years, they had fled to Mexico City, where they hung out in the same circles that Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera had frequented, and that muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros did at the time they were there.

Susan and friend Roxanne make a stab at sophistication, 1959 or 1960. Courtesy of Susan Griffin.

Susan went on to study at UC Berkeley—where she protested against the House Un-American Activities Committee, picketed Woolworth’s, and joined a sit-in at the Sheraton Palace Hotel against racist hiring practices. She worked as a strawberry picker for one scorching summer day so that she could testify to a federal committee on labor about farm worker conditions. Then, after a summer in San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood where the likes of Allen Ginsburg, Lawrence Ferlingetti, and Diane di Prima had downed espresso, written books, and held poetry readings, she transferred across the Bay to complete a B.A. in Creative Writing at San Francisco State. Afterward, she worked at Warren Hinckle’s New Left magazine Ramparts. She got married, gave birth to her daughter Chloe Andrews (née: Levy), and returned to SF State to complete a master’s degree.

Around 1986-87 Susan became ill with a strange, unidentified sickness. Knocked out by exhaustion, muscle aches, and joint pain, she began to spend what would become several years of active affliction, close to or in bed. Other people, particularly women—among them feminists Hallie Iglehart Austin, Phyllis Chesler, Kim Chernin, and Naomi Weisstein—were suffering similar symptoms, and at last, against adamant denial by the medical profession and insurance companies, an alarmed minority of researchers launched investigations to understand this fast-spreading illness. The results of their efforts revealed a host of changes in the bodies of the affected cohort: lowered hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, brain lesions similar to those found in AIDS and Alzheimer’s patients, high levels of protective immunological titers in the blood, and deficiency of the natural killer cells that normally combat viruses. It was speculated that a virus was the culprit, and the disease was termed Chronic Fatigue Immune Dysfunction Syndrome.

During this pained period of Susan’s life, I occasionally traveled from New Mexico to the Bay Area and stayed at her house—mingling my work activities with picking up things she needed, cooking, and watching films together on video. Stunningly, her perspective on the tragedy was not just personal, it was global. “In a terrible way, no one who has CFIDS is truly alone,” she wrote in Ms. magazine. “Sadly, we are all part of this global process. Those who are ill [are] like canaries in the mine—our sickness a signal of the sickness of the planet. An epidemic of breast cancer, the rising rate of lupus, M.S., a plethora of lesser-known disorders of the immune system.”

Like a heroine in a mythic tale, despite her infirmity, Susan did not stop participating in life. Postmodernism was just arising as the new interpretation of social reality in computerized mass society. It was hard for me to grasp, living as I was in the more rooted environ of a land-based village struggling to preserve its traditions, but Susan had already digested the essence of the new thinking and begun to critique its assertions in ways that would later be written about by thinkers like Noam Chomsky, Melford Spiro, and Charlene Spretnak. As the illness lost its force and she could concentrate better, ever so emblematic of the feminist axiom “the personal is political,” she penned What Her Body Thought about the experience.

And she had lovers. “The hope you feel when you are in love is not necessarily for anything in particular,” she wrote in What Her Body Thought. “Love brings something inside you to life. Perhaps it is just the full dimensionality of your own capacity to feel that returns. In this state you think no impediment can be large enough to interrupt your passion. The feeling spills beyond the object of your love to color the whole world. The mood is not unlike the mood of revolutionaries in the first blush of victory, at the dawn of hope. Anything seems possible.” During the early 1980s Susan loved and lived with writer Kim Chernin. In 1989 she fell for Tikkun publisher Nan Fink, and they renovated Nan’s house—Susan building a light-filled office and bedroom by the back rose garden and Nan using the older front side of the residence.

Needless to say, the humor, soul, brainpower, and drive unfurl still. Susan has finished a novel called The Ice Dancer’s Tale about an ice skater from California who, with the guidance of a shaman from the Arctic, “creates an ice dance about climate change that transforms the consciousness of anyone who sees it.” Her goal for the coming years is to complete an epic poem inspired by the Mississippi River, and, true to her roots in the women’s movement, she has begun a nonfiction work about misogyny and the threat of fascism.

LUCY LIPPARD: SOCIAL COLLAGIST

(1937–)

Art must have begun as nature—not as imitation of nature, nor as formalized representation of it, but simply as the perception of relationships between humans and the natural world.

—L.L., OVERLAY, 1983

Lucy Lippard sends postcards. By now there must be enough of them—penned in near-illegible scrawl and mailed to the four winds—to fill an exposition at the Brooklyn Museum of Art. Such an exhibit would be emblematic of Lucy’s originality. Officially known as an art critic, in fact her roles span from cultural intellectual to street rabble-rouser, from twenty-plus-book author to hands-on curator, from university lecturer to radical political activist. She is a woman so crossover inventive that she has been dubbed not just a bystanding commentator on art—but a “Dada-esque strategist.” Or, as she might say, a social collagist.

Aside from her name festooning the masthead of the New York feminist magazine Heresies, Lucy became a reality for me in Susan Griffin’s living room on Hawthorne Terrace in 1983. Here was her new book, a photographic text—a prose poem, really—revealing the similarities of contemporary women’s art with ancient creations of Paleolithic, Neolithic, and indigenous peoples. Overlay was about the most relevant piece of research to hit the bookstores I could have imagined. In the women’s spirituality wing of the feminist movement, we were focused on unearthing pre-patriarchal times when women were honored and held valued social positions, when the moon as reality/symbol held equal influence as the male-associated sun. We were steeped in the cave paintings of Lascaux, the Venus sculptures, the figurines of matriarchal Catal Huyuk, as well as the circular stone construction at Stonehenge—and now here was evidence of the unconscious mind of the twentieth century reiterating these earlier archetypes in painting, photography, and earth sculpture.

In 1973 Lucy’s insights about conceptual art as documented in Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972 had flung her into the track lighting of the national art scene. Just as her topic was controversial, so was her approach. The book is a photo poem, a bibliography arranged chronologically, between which are inserted fragments of text, interviews, documents, and artworks. Lucy had written five books before: works on Philip Evergood, Dada, Pop Art, and Surrealism, and a collection of her art criticism. By the mid-1970s she was covering such developments as land art, minimalism, systems, anti-form, and feminist art. “Conceptual art, for me,” she wrote, “means work in which the idea is paramount and the material form is secondary, lightweight, ephemeral, cheap, unpretentious and/or ‘dematerialized.’” Linking changes in American society such as the eruption of the civil rights, women’s rights, and anti-Vietnam War movements to their ramifications in artistic expression, her insights offered social context to the task of understanding such otherwise inscrutable artists as Yoko Ono, Robert Barry, Eva Hesse, and Lawrence Weiner.