ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

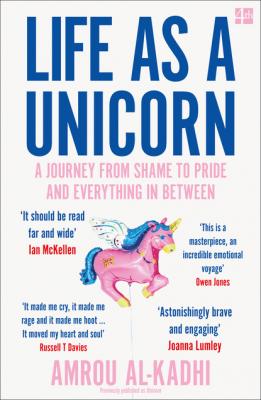

Unicorn. Amrou Al-Kadhi

Читать онлайн.Название Unicorn

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780008306083

Автор произведения Amrou Al-Kadhi

Жанр Биографии и Мемуары

Издательство HarperCollins

My father was clearly insecure about the unashamed preference I had for Mama, so one evening he took Ramy and me out to dinner for ‘a boys’ night’. I dreaded the evening to my core. Not because I didn’t want to be with them, but because I didn’t want to be apart from Mama. To be honest, I can’t remember much of the evening, except one quite alarming moment. As I excused myself to go to the toilet for the eighth time during the main course, I glimpsed the back of Mama’s head at a table in the smoking section of the restaurant (a smoking section – how vintage!). I felt suddenly elated that my time in the boys’ corner might be over sooner than I expected. I sprinted over to her and wrapped my arms around her neck as if we were two conjoined swans, burrowing myself into her hair. She jumped up in shock and turned around, severing me from her embrace as she did so. When I looked up at her … she was not my mother. She was just another Arab woman of my mother’s age (who potentially used the same hairdresser). I apologised, and drooped back to Baba and Ramy, embarrassed and upset. All I wanted was to be with Mama. I was all about my mother.

When it was just me and Mama, we created a pocket of ‘camp’ that only we were privy too. And it was in this special fortress that my love of performance was born. Now, Dubai and Bahrain had no culture of theatre – literally, none – and so my only access was a VHS tape of CATS on the West End that I received as a gift from some cousins in London. Until I was a teenager, I thought CATS was the pinnacle of Britain’s rich theatrical history. In truth, I believed that it was the only real bit of theatre that mattered. The first time I watched it, I was struck by the way male bodies were celebrated for their balletic curves, how they flaunted chic feline poses with utter pride, sitting side by side with the female performers without any shame. Now, my homosexual desires hadn’t quite taken shape when I was nine, and sexual desire was not a concept anyone articulated (in fact, one of my Muslim cousins only learnt that pregnancy was the result of sex, rather than marriage, at the age of sixteen); but the way that the musculature of the male performers was embellished by their spandex costumes sparked a feeling in me that had been lying dormant until that moment. All I have to do is get to London, and then I’ll be able to roll around with the spandex male cats. This became a definitive, serious ambition of mine, and I told my mother that I wanted to be a performer so that I could be in CATS in the West End one day.

Because Bahrain was so bereft of theatre, Mama turned into Miss Marple in her quest to find me a stage – no doubt my midnight impersonation of Umm Kulthum had convinced her of my chops. Her investigative efforts led her to discover that the British Council often held a Christmas pantomime as a way to preserve the cultural tradition. She called them up and explained that her young son was desperate for a part – but they said this was more a production for British citizens living in the Middle East. My brother and I had British passports; when we were yet unborn in our mother’s tummy, she and my dad had left Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq and we were born in Camden, thus granting us immediate British citizenship (Theresa May wasn’t in the Home Office yet). But then they told Mama that there were no roles for children in the pantomime. Undeterred, with the might of Umm Kulthum, and the tenacity of Erin Brockovich, Mama marched me into the British Council building the next day, and demanded they give me a part. But in this amateur production of Cinderella, there just wasn’t a part for a child. And so we were forced to drive home, tears running down my face, in a melodramatic tableau I wish had been filmed for posterity.

The next evening, as I mourned my non-existent pantomime career on the sofa in front of the TV, Mama came running from the kitchen, excitement all over her face as if she’d just won the lottery. ‘Amoura! Pick up the house phone – there’s someone on the line.’ Was it Baba, wanting to know if I’d join him and Ramy at the kebab shop for the umpteenth time? I had an excuse pursed on my lips, but I was caught completely by surprise – it was the director of the pantomime! He said he was so impressed with my determination to have a role in his production, that he had written one into the script for me – yes, you heard me: a role created specially for me.

To my knowledge, this character existed in no version of Cinderella throughout history, but I was ecstatic nonetheless. For I was going to be premiering the never-before-seen role of … the Fairy Godmother’s gecko. You heard it. A gecko. In Cinderella. My first foray into show business was to play a GECKO in a story that had nothing to do with geckos. Who knows, maybe the casting of a brown boy as an exotic reptile was rooted in systemic colonial structures – this was the British Council after all – but at the time, I felt nothing but victorious.

Rehearsals were after school every evening. I was the only child in the production, and because the gecko was – surprise! – not exactly integral to the plot, I really wasn’t needed much. However, I told Mama that I needed to be at every single rehearsal if I was going to do the part any justice. What is the world this gecko is inhabiting? Is this gecko scared of the Ugly Sisters too? Has the gecko been watching Cinderella’s abuse their whole life? – there were many urgent things to interrogate. In reality, all I had to do was stand in front of Cinderella as she got changed from rags to riches in the ball sequence. Effectively, I was a shield – a role so perfunctory that at the last minute they roped in my twin brother so that he could provide extra blockage. Despite my role as a wall divide, Mama sat with me in every single rehearsal as I soaked up the colourful world of pantomime and its diverse cast of performers.

Remember how, as a kid, a lot of your time was spent looking up at adults with a fiery curiosity? Remember how BIG every grown-up seemed? How each grown-up was like a speculative mirror to your future self, and you imagined yourself living the incredible lives you presumed they had? And there were some grown-ups who seemed different to any other grown-up you’d seen before – who took on a prophetic status, as if your paths crossing was an act of divine intervention? There were two such adults in the pantomime – and they were the grown men playing the Ugly Sisters. Both were from England, in their late thirties/early forties, and with hindsight I think they were a couple, but at the time I believed them to be best friends. From my minuscule height they seemed to have imposing, manly frames, yet they gestured with their hands as if they were flicking wands, oozing wit and comic flare – what we might term ‘camp’. ‘Were you in CATS?’ I asked them one evening with complete sincerity, at which they laughed from the belly, one of them commenting: ‘Darling, I wish.’ Yes, I wish too. We get each other.

During one dress rehearsal, I was completely blown away when both men came onto the stage in women’s clothing. I remember their costumes vividly; one of them had bright orange pigtails, radio-active fuchsia lips, and freckles dotted all over his face, while the other had a plum-toned up-do of a shape not dissimilar to Umm Kulthum’s. The former had what looked like a pink chequered apron flowing down his body, while the other was strapped into a purple corset and black thigh-high boots. With little conception of my gender or sexuality at this point, I can’t remember processing my own dysphoria or sexual orientation within what I was seeing – the overarching feeling I had was, ‘is this allowed?’ I looked around the room, seeing the rest of the cast laugh and celebrate both men in their feminine get-ups. The pair were melding the masculine and the feminine, transgressing both, relishing both, and there was nothing dangerous about it – all it brought into the room was a feeling of collective joy. Just as Umm Kulthum’s voice could apparently overcome audience gender divides, again I was witnessing the potential of femininity to alter social space. Rules and codes of behavioural conduct formed a major part of Islamic teachings, so the idea of a man transgressing his gender codes was not something I thought I’d ever see publicly in the Middle East. But here, in front of me, were men wearing women’s clothing, and the only reactions they provoked were ones of enjoyment. I was smiling goofily, and, as I turned to my mother, I could see that she too was enjoying the performance of the two infectious, loveable queens. Mama’s enjoying this too! Maybe not being a manly boy will be OK with Mama! It seemed that in our secret club, these other ways of being were tolerated – celebrated, even. Perhaps I had nothing to worry about.

But, as I would shortly learn, Mama’s and my bubble was going to burst. And in the next phase of my life, nothing could have prepared me for how sharp a turn Mama would take to stop me being