ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

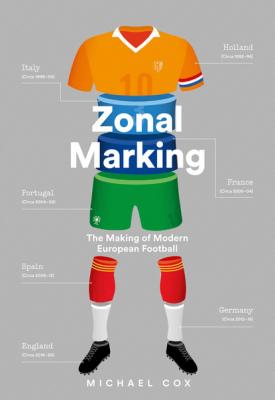

Zonal Marking. Michael Cox

Читать онлайн.Название Zonal Marking

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780008291150

Автор произведения Michael Cox

Издательство HarperCollins

‘In Spain, everything that comes from Italy is seen in a negative light,’ said defender José Amavisca, quoted in Gabriele Marcotti’s biography of Capello. ‘Because he’s Italian, everything Capello did was seen as ugly, dirty, nasty or boring.’ Capello’s training sessions were typically Italian: long periods spent drilling the back four into the correct shape, and a strong emphasis on hardcore fitness work. He spent much of the season squabbling with Sanz, the Real president, partly because Capello consistently refused to select his son Fernando, a graduate of the club’s academy. He also encountered problems with forwards Mijatović and Šuker, who were frequently substituted when Capello summoned defensive reinforcements. ‘My matches only ever last 75 minutes,’ complained Šuker. More than half of the Croatian’s La Liga starts ended with his withdrawal, a stark contrast to the star treatment Real Madrid forwards are usually afforded. His replacement was always a defender or defensive midfielder.

Capello was justified in sacrificing big names, because his tactical acumen was outstanding. During 1996/97 Real Madrid regularly started poorly and found themselves a goal behind, before Capello’s instructions enabled them to readjust and clinch victory. Real came from behind to win with incredible regularity: against Real Sociedad, Valencia, Atlético Madrid, Deportivo de La Coruña, Hércules, Racing Santander, Sevilla and Sporting Gijón.

The Sevilla comeback, in mid-April, was most significant. Capello started with his usual 4–4–2, with Raúl drifting inside from the left, but Real were absolutely battered by a rampant Sevilla, particularly down the flanks. Tarik Oulida, the Ajax-schooled left-winger, crossed for right-winger José Mari to head home in the first minute, then Oulida made it 2–0. Real could have easily been 4–0 down. Therefore, Capello made two tactical changes midway through the first half. Veteran defender Manuel Sanchís replaced beleaguered right-back Chendo. Next, Capello sacrificed Šuker and introduced defensive midfielder Zé Roberto. The home supporters were understandably bemused; at 2–0 down Real needed goals, and Capello had taken off a striker.

First, though, Capello knew Real required defensive solidity. Raúl pushed up front, Zé Roberto played on the left of a midfield diamond and screened Roberto Carlos. Real now coped down the flanks and could work their way into the game. On the stroke of half-time, Clarence Seedorf got a goal back, then Raúl scored the equaliser in the second half. Hierro headed home seven minutes from time, and then Seedorf teed up Mijatović. Real had been 2–0 down, Capello had made two first-half substitutions purely for tactical reasons, including substituting his top scorer, and they ended up winning 4–2.

Winning in this fashion would have been celebrated in Capello’s home country, but Real demanded more spectacular performances, and despite the title success, this was a loveless marriage that lasted just a year. Curiously, a decade later Capello returned for a second spell at the Bernabéu, with somewhat familiar consequences; he won the league, then he was sacked. ‘We have to find a coach who gives us a bit more,’ said Real’s sporting director, after Capello’s second departure. ‘We need a coach who, as well as getting results – which are very important – can help us enjoy our football again.’ The identity of the sporting director? Mijatović, the frequently substituted forward from Capello’s first stint. Two seasons, two titles, two acrimonious departures. Italian methods were not popular outside Italy.

But they were clearly conducive to success, because the three most respected Italian coaches of this era completed an extraordinary treble in 1996/97. Lippi triumphed in Serie A with Juventus, Capello was victorious in La Liga with Real Madrid, while Giovanni Trapattoni won the Bundesliga with Bayern Munich.

This was Trapattoni’s second spell with Bayern, after a disappointing 1994/95 campaign that he blamed on not mastering German properly, although upon his return his communication skills had only improved slightly. Trapattoni initially attempted to use a four-man defence, before reverting to the sweeper system that was more typically German, and indeed more typically Trapattoni, after some disappointing early results, including a 3–1 aggregate UEFA Cup defeat to Valencia. ‘Too many changes have upset their rhythm,’ claimed Trapattoni’s predecessor Otto Rehhagel after that European exit. ‘Bayern are paying for the mistakes in signing the wrong players and not sticking to a definite tactical system.’ Not sticking to a definite tactical system, though, was entirely Trapattoni’s plan.

His tactical tinkering continued to frustrate and caused problems among his key players. In late November Bayern were 2–0 up at half-time against relegation strugglers Hansa Rostock, so Trapattoni ordered his players to concentrate on keeping a clean sheet. But centre-forward Jürgen Klinsmann encouraged his teammates to continue attacking. The players were caught in two minds, conceded 20 minutes into the second half and limped to a 2–1 victory. ‘That’s why we lost our shape,’ complained left-wing-back Christian Ziege. ‘One defensive player would make a forward run, and everyone else would stay back and watch him disappear into the distance. Very confusing.’ But Trapattoni’s focus on tactical discipline, and his refusal to indulge FC Hollywood’s superstars, proved successful; compared with the previous campaign, Bayern only scored two more goals, but they conceded 12 fewer. ‘Under him, I learned how to defend,’ explained midfielder Mehmet Scholl. ‘But I also learned that if I played a bad pass, I would be substituted.’

Just like Capello in Madrid, Trapattoni’s substitutions proved particularly controversial in Munich, particularly with Klinsmann, who took a break from squabbling with long-time foe Lothar Matthäus to row with Trapattoni instead. Klinsmann knew exactly what to expect, having previously played under Trapattoni at Inter, but he frequently complained about the Italian’s defensive tactics and about being hauled off midway through the second half, generally so Trapattoni could introduce a defensive player. The final straw came three games from the end of the campaign, in a 0–0 home draw with Freiburg. Trapattoni summoned youngster Carsten Lakies for his first – and last – Bundesliga appearance, in place of Klinsmann, who screamed at Trapattoni on his way off, made an ‘It’s over’ hand gesture and then furiously booted a large, battery-shaped advertising hoarding, momentarily getting his foot stuck. ‘I was just trying to open the game up a bit,’ explained Trapattoni afterwards, gesturing as if he wanted more runs from wider positions.

The advertising hoarding later found its way into Bayern’s museum, a monument to Klinsmann’s rage and Trapattoni’s ultra-Italian tendency to sacrifice stars when tactically necessary. Bayern won the league and, after the celebratory parade, Trapattoni, in traditional Bavarian dress, treated Bayern’s supporters to some Italian songs from the balcony of Munich’s town hall. It was indeed over for Klinsmann after winning his only league title – he returned to Serie A, joining Sampdoria. ‘I wanted a club where the philosophy of football was right for me,’ he announced. ‘Sampdoria is that club and César Menotti is that sort of coach.’ It was a pointed dig at Trapattoni.

‘As an Italian coach in Germany, I was trying to change their mindset,’ remembered Trapattoni. ‘I was met with resistance, because you don’t change a mentality in two or three months. I wanted them to get accustomed to thinking tactically, developing the play and seeking options. I had to let them play their way and gradually blend in my tactics. After my first year, they began to change a little, but it was a cultural clash. In Germany, they follow a fixed plan. In Italy, we are more flexible.’

Trapattoni’s second campaign was less successful, and was most notable for his infamous press-conference rant in broken German, during which he screamed into the microphone, justifying his decision to omit Scholl, a classy playmaker, and Mario Basler, an unpredictable winger, neither of whom had been pulling their weight defensively. Trapattoni was keen to stress that Bayern played positive football in his diatribe. ‘No team in Germany plays attacking football like Bayern,’ he declared. ‘In the last game, on the pitch we had three strikers – Giovane Élber, Carsten Jancker and Alexander Zickler. We mustn’t forget Zickler! Zickler is a striker, more than Scholl, more than Basler!’ Even in this irritated state, Trapattoni felt compelled to underline that his selection wasn’t too defensive, too Italian.