ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

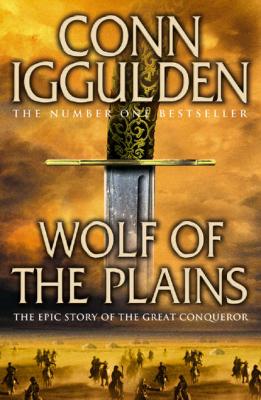

Wolf of the Plains. Conn Iggulden

Читать онлайн.Название Wolf of the Plains

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780007285341

Автор произведения Conn Iggulden

Издательство HarperCollins

Temujin stared after his father as he rode, returning to his brothers, his mother, everything he loved. Though he knew he would not, Temujin hoped Yesugei would glance back before he was out of sight. He felt tears threaten and took a deep breath to hold them back, knowing it would please Enq to see weakness.

His uncle watched Yesugei leave and then he closed one nostril with a finger, blowing the contents of the other onto the dusty ground.

‘He is an arrogant fool, that one, like all the Wolves,’ he said.

Temujin turned quickly, surprising him. Enq sneered.

‘And his pups are worse than their father. Well, Sholoi beats his pups as hard as he beats his daughters and his wife. They all know their place, boy. You’ll learn yours while you are here.’

He gestured to Sholoi and the little man took Temujin’s arm in a surprisingly powerful grip. Enq smiled at the boy’s expression.

Temujin held silent, knowing they were trying to frighten him. After a pause, Enq turned and walked away, his expression sour. Temujin saw that his uncle limped much worse when Yesugei was not there to see it. In the midst of his fear and loneliness, that thought gave him a scrap of comfort. If he had been treated with kindness, he may not have had the strength. As things stood, his simmering dislike was like a draught of mare’s blood in his stomach, nourishing him.

Yesugei did not look back as he passed the last riders of the Olkhun’ut. His heart ached at leaving his precious son in the hands of weaklings like Enq and Sholoi, but to have given Temujin even a few words of comfort would have been seen as a triumph for those who looked for such things. When he was riding alone across the plain and the camp was far behind, he permitted himself a rare smile. Temujin had more than a little fierceness in him, perhaps more than any other of his sons. Where Bekter might have retreated into sullenness, he thought Temujin might surprise those who thought they could freely torment a khan’s son. Either way, he would survive the year and the Wolves would be stronger for his experiences and the wife he would bring home. Yesugei remembered the fat herds that roamed around the gers of his wife’s tribe. He had found no true weaknesses in the defences, but if the winter was hard, he could picture a day when he would ride amongst them once more, with warriors at his side. His mood lightened at the thought of seeing Enq run from his bondsmen. There would be no smiles and sly glances from the thin little man then. He dug in his heels to canter across the empty landscape, his imagination filled with pleasant thoughts of fire and screaming.

Temujin came abruptly from sleep when a pair of hands yanked him off his pallet and onto the wooden floor. The ger was filled with that close darkness that prevented him from even seeing his own limbs, and everything was unfamiliar. He could hear Sholoi muttering as he moved around and assumed it was the old man who had woken him. Temujin felt a surge of fresh dislike for Borte’s father. He scrambled up, stifling a cry of pain as he cracked his shin on some unseen obstacle. It was not yet dawn and the camp of the Olkhun’ut was silent all around. He did not want to start the dogs barking. A little cold water would splash away his sleepiness, he thought, yawning. He reached out to where he remembered seeing a bucket the evening before, but his hands closed on nothing.

‘Awake yet?’ Sholoi said somewhere near.

Temujin turned towards the sound and clenched his fists in the darkness. He had a bruise along the side of his face from where the old man had struck him the evening before. It had brought shameful tears to his eyes, though he’d seen that Enq had spoken the truth about life in that miserable home. Sholoi used his bony hands to enforce every order, whether he was moving a dog out of his path, or starting his daughter or wife to some task. The shrewish-looking wife seemed to have learned a sullen silence, but Borte had felt her father’s fists more than a few times on that first evening, just for being too close in the confined space of the ger. Under the dirt and old cloth, Temujin thought she must have been covered in bruises. It had taken two sharp blows from Sholoi before he too kept his head down. He’d felt her eyes on him then, her gaze scornful, but what else could he have done? Killed the old man? He didn’t think he would live long past Sholoi’s first shout for help, not surrounded by the rest of the tribe. He thought they would take a particular delight in cutting him if he gave them cause. His last waking thought the night before had been the pleasant image of dragging a bloody Sholoi behind his pony, but it was just a fantasy born of humiliation. Bekter had survived, he reminded himself, sighing, wondering how the big ox had managed to hold his temper.

He heard a creak of hinges as Sholoi opened the small door, letting in enough cold starlight for Temujin to edge around the stove and past the sleeping forms of Borte and her mother. Somewhere nearby were two other gers with Sholoi’s sons and their grubby wives and children. They had all left the old man years before, leaving only Borte. Despite his rough ways, Sholoi was khan in his own home and Temujin could only bow his head and try not to earn too many cuffs and blows.

He shivered as he stepped outside, crossing his arms in his thick deel so that he was hugging himself. Sholoi was emptying his bladder yet again, as he seemed to need to do every hour or so in the night. Temujin had woken more than once as Sholoi stumbled past him and he wondered why he had been pulled from the blankets this time. He felt a deep ache in his stomach from hunger and looked forward to something hot to start the day. With just a little warm tea, he was certain he would be able to stop his hands shaking, but he knew Sholoi would only cackle and sneer if he asked for some before the stove was even lit.

The herds were dark figures under the starlight as Temujin emptied his own urine into the soil, watching it steam. The nights were still cold in spring and he saw there was a crust of ice on the ground. With a south-facing door, he had no trouble finding east, to look for the dawn. There was no sign of it and he hoped Sholoi did not rise at such an early hour every day. The man may have been toothless, but he was as knotted and wiry as an old stick and Temujin had the sinking feeling that the day would be long and hard.

As he tucked himself in, Temujin felt Sholoi’s grip on his arm, pushing at him. The old man held a wooden bucket, and as Temujin took it, he picked up another, pressing it into his free hand.

‘Fill them and come back quick, boy,’ he said.

Temujin nodded, turning towards the sound of the nearby river. He wished Khasar and Kachiun could have been there. He missed them already and it was not hard to imagine the peaceful scene as they awoke in the ger he had known all his life, with Hoelun stirring them to begin their chores. The buckets were heavy as he headed back, but he wanted to eat and he did not doubt Sholoi would starve him if he gave him an opportunity.

The stove had been lit by the time he returned and Borte had vanished from her blankets. Sholoi’s grim little wife, Shria, was fussing around the stove, nursing the flames with tapers before shutting the door with a clang. She had not spoken a word to him since his arrival. Temujin looked thirstily at the pot of tea, but Sholoi came in just as he put the buckets down and guided him back out into the quiet darkness with a two-fingered grip on his bicep.

‘You’ll join the felters later, when the sun’s up. Can you shear?’

‘No, I’ve never had …’ Temujin began.

Sholoi grimaced. ‘Not much good to me, boy, are you? I can carry my own buckets. When it’s light you can collect sheep turds for the stove. Can you ride herd?’

‘I’ve done it,’ Temujin replied quickly, hoping he would be given his pony to tend the Olkhun’ut sheep and cattle. That would at least take him away from his new family for a while each day. Sholoi saw