ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

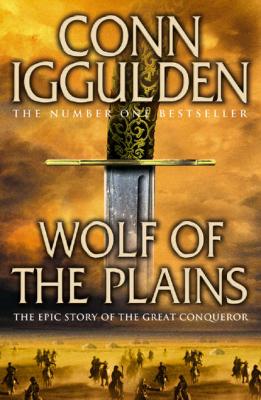

Wolf of the Plains. Conn Iggulden

Читать онлайн.Название Wolf of the Plains

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780007285341

Автор произведения Conn Iggulden

Издательство HarperCollins

‘You have the bird?’ Yesugei said to Temujin, taking a step forward.

The boy could not hold back his excitement any longer and he grinned, standing proudly as he fished around inside his tunic.

‘Kachiun and I found two,’ he said.

His father’s cold face broke at this and he showed his teeth, very white against his dark skin and wispy beard.

Gently, the two birds were brought out and placed in their father’s hands, squalling as they came into the light. Temujin felt the loss of their heat next to his skin as soon as they were clear. He looked at the red bird with an owner’s eyes, watching every movement.

Yesugei could not find words. He saw that Eeluk had come closer to see the chicks and he held them up, his face alight with interest. He turned to his sons.

‘Go in and see your mother, all of you. Make your apologies for frightening her and welcome your new sister.’

Temuge was through the door of the ger before his father had finished speaking and they all heard Hoelun’s cry of pleasure at seeing her youngest son. Kachiun and Khasar followed, but Temujin and Bekter remained where they were.

‘One is a little smaller than the other,’ Temujin said, indicating the birds. He was desperate not to be dismissed. ‘There is a touch of red to his feathers and I have been calling him the red bird.’

‘It is a good name,’ Yesugei confirmed.

Temujin cleared his throat, suddenly nervous. ‘I had hoped to keep him, the red bird. As there are two.’

Yesugei looked blankly at his son. ‘Hold out your arm,’ he said.

Temujin raised his arm to the shoulder, puzzled. Yesugei held the pair of trussed chicks in the crook of one arm and used the other to press against Temujin’s hand, forcing his arm down.

‘They weigh as much as a dog, when they are grown. Could you hold a dog on your wrist? No. This is a great gift and I thank you for it. But the red bird is not for a boy, even a son of mine.’

Temujin felt tears prickle his eyes as his morning’s dreams were trampled. His father seemed oblivious to his anger and despair as he called Eeluk over.

To Temujin’s eye, Eeluk’s smile was sly and unpleasant as he came to stand by them.

‘You have been my first warrior,’ Yesugei said to the man. ‘The red bird is yours.’

Eeluk’s eyes widened with awe. He took the bird reverently, the boys forgotten. ‘You honour me,’ he said, bowing his head.

Yesugei laughed aloud. ‘Your service honours me,’ he replied. ‘We will hunt with them together. Tonight we will have music for two eagles come to the Wolves.’ He turned to Temujin. ‘You will have to tell old Chagatai all about the climb, so that he can write the words for a great song.’

Temujin did not reply, unable to stand and watch Eeluk holding the red bird any longer. He and Bekter ducked through the low doorway of the ger to see Hoelun and their new sister, surrounded by their brothers. The boys could hear their father outside, shouting to the men to see what his sons had brought him. There would be a feast that night and yet, somehow, they were uncomfortable as they met each other’s eyes. Their father’s pleasure meant a lot to all of them, but the red bird was Temujin’s.

That evening, the tribe burned the dry dung of sheep and goats and roasted mutton in the flames and great bubbling pots. The bard, Chagatai, sang of finding two eagles on a red hill, his voice an eerie combination of high and low pitch. The young men and women of the tribe cheered the verses and Yesugei was pressed into showing the birds again and again while they called piteously for their lost nest.

The boys who had climbed the red hill accepted cup after cup of black airag as they sat around the fires in the darkness. Khasar went pale and silent after the second drink, and after a third, Kachiun gave a low snort and fell slowly backwards, his cup tumbling onto the grass. Temujin stared into the flames, making himself night blind. He did not hear his father approach and he would not have cared if he had. The airag had heated his blood with strange colours that he could feel coursing through him.

Yesugei sat down by his sons, drawing his powerful legs up into a crouch. He wore a deel robe lined with fur against the night cold, but underneath, his chest was bare. The black airag gave him enough heat and he had always claimed a khan’s immunity from the cold.

‘Do not drink too much, Temujin,’ he said. ‘You have shown you are ready to be treated as a man. I will complete my father’s duty to you tomorrow and take you to the Olkhun’ut, your mother’s people.’ He saw Temujin look up and completely missed the significance of the pale golden gaze. ‘We will see their most beautiful daughters and find one to warm your bed when her blood comes.’ He clapped Temujin on the shoulder.

‘And I will stay with them while Eeluk raises the red bird,’ Temujin replied, his voice flat and cold. Some of the tone seeped through Yesugei’s drunkenness and he frowned.

‘You will do as you are told by your father,’ he said. He struck Temujin hard on the side of his head, perhaps harder than he had meant to. Temujin rocked forward, then came erect once again, staring back at his father. Yesugei had already lost interest, looking away to cheer as Chagatai stirred his old bones in a dance, his arms cutting the air like an eagle’s wings. After a time, Yesugei saw that Temujin was still watching him.

‘I will miss the gathering of tribes, the races,’ Temujin said, as their eyes met, fighting angry tears.

Yesugei regarded him, his face unreadable. ‘The Olkhun’ut will travel to the gathering, just as we will. You will have Whitefoot. Perhaps they will let you race him against your brothers.’

‘I would rather stay here,’ Temujin said, ready for another blow.

Yesugei didn’t seem to hear him. ‘You will live a year with them,’ he said, ‘as Bekter did. It will be hard on you, but there will be many good memories. I need not say that you will take note of their strength, their weapons, their numbers.’

‘We have no quarrel with the Olkhun’ut,’ Temujin said.

His father shrugged. ‘The winter is long,’ he replied.

Temujin’s head throbbed in the weak dawn light as his father and Eeluk loaded the ponies with food and blankets. Hoelun was moving around outside, her baby daughter suckling inside her coat. She and Yesugei talked in low voices and, after a time, he bent down to her, pressing his face into the crook of her neck. It was a rare moment of intimacy that did nothing to dispel Temujin’s black mood. That morning, he hated Yesugei with all the steady force a twelve-year-old boy can muster.

In grim silence, Temujin continued to grease his reins and check every last strap and knot on the halter and stirrups. He would not give his father an excuse to criticise him in front of his younger brothers. Not that they were anywhere to be seen. The ger was very quiet after the drinking the night before. The golden eagle chick could be heard calling for food and it was Hoelun who ducked through the door to feed it a scrap of bloody flesh. The task would be hers while Yesugei was away, but it hardly distracted her from making sure her husband was content and had all he needed for the trip.

The ponies snorted and called to each other, welcoming another day. It was a peaceful scene and Temujin stood in the middle like a sullen growth, looking for the smallest excuse to lash out. He did not want to find himself some cow-like wife. He wanted to raise stallions and ride with the red bird, known and feared. It felt like a punishment to be sent away, for all he knew that