ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

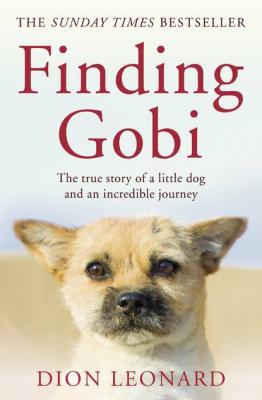

Finding Gobi. Dion Leonard

Читать онлайн.Название Finding Gobi

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780008227975

Автор произведения Dion Leonard

Жанр Биографии и Мемуары

Издательство HarperCollins

I was born in Sydney, New South Wales, but grew up in an Australian outback town in Queensland called Warwick. It’s a place that barely anyone I meet has visited but one that contains the kind of people everyone can recognize. It’s farming country, with traditional values and a strong emphasis on family. These days it’s changed a lot and become a small, vibrant city, but when I was a teenager, Warwick was the kind of place that would fill up on a Friday night. The pubs would be crammed with hardworking men looking for a good night out involving a few too many beers, a couple of fights, and a trip to the petrol station—which any self-respecting Australian calls the ‘servo’—for a meat pie that had been kept in a warmer all day and was hard as a rock.

They were good people, but it was a cliquish town at the time, and everyone knew everyone else’s business. I knew I didn’t belong among them.

It wasn’t just the scandal of my abnormal childhood and family situation that prompted people to react badly. It was the way I behaved. It was who I had become. I went from being a polite, pleasant little kid to an awkward, pain-in-the-ass loudmouth. By the time I was fourteen, I was the class joker, riling the teachers with my crowd-pleasing comments, getting thrown out of class, and swaggering my way out of the school gates as I walked to the servo for an early afternoon pie while the other fools were still stuck in class.

And when my school year ended and the headmaster greeted each of us with a handshake and a friendly word about our futures at the final assembly, all he could say to me was, “I’ll be seeing you in prison.”

Of course, there was a reason for all this, and it wasn’t just the pain of losing my dad—not just once but twice over.

I was falling apart because everything at home seemed to me to be falling apart.

It seemed the loss of her husband hit my mum hard. Really hard. Her own father had returned from the Second World War traumatized, and like so many men, he turned to alcohol to numb the pain. Mum’s childhood taught her that when parents are struggling, home isn’t always the best place to be.

So when Mum became a widow in her early thirties with two young children, she coped the only way she knew how. She retreated. I remember days would go by and she’d be locked in the bedroom. I cooked meals of eggs on toast or spaghetti out of a can, or else we went to Nan’s, some other neighbour’s house, or, if it was Sunday, church.

From what I could see, Mum would go through phases where she became fixated with keeping the house immaculate. She cleaned relentlessly, and on the odd occasion that she did cook for herself, she’d clean the kitchen frantically for two hours. Neither I nor my little sister, Christie, could do anything right. Kids being kids, if we’d leave crumbs around the place, smear our finger marks on windows, or take showers that lasted longer than three minutes, it might upset her.

Ours was a half-acre, filled with trees and flower beds. While Mum and Dad used to love working in it together, after Dad’s death it was up to me to get out and keep it tidy. If I didn’t do my chores, I felt life wasn’t worth living.

When Mum would start nagging at me, pretty soon she’d be yelling at me and screaming. “You’re useless,” she’d say. I’d scream and yell back, and soon we both would be swearing at each other. Mum never apologized. Nor did I. But we both had said things we’d later regret.

We argued endlessly, every day and every night. I’d come home from school and feel like I had to walk on eggshells around the house. If I made any noise or disturbed her in any way, the whole fighting thing would start up again.

By the time I was fourteen, she’d had enough. “You’re out,” she said one day as, following yet another storm of mutually hurled insults, she pulled out cleaning supplies from the cupboard. “There’s too much arguing, and nothing you do is right. You’re moving downstairs.”

The house was a two-storey home, but everything that mattered was upstairs. Downstairs was the part of the house where nobody ever went. It was where Christie and I played when we were little, but since then the playroom had become a dumping ground. There was a toilet down there, but barely any natural light, and a big area that was still full of building supplies. Most important for my mum, there was a door at the base of the stairway that could be locked. Once I was down there, I felt trapped, stopped from being part of the family life above.

I didn’t argue with her. Part of me wanted to get away from her.

So I moved my mattress and my clothes and settled into my new life—a new life in which Mum would open the door when it was time for me to come up and get food or when I needed to go to school. Apart from that, if I was at home, I was confined to the basement.

The thing I hated most about it was not the fact that I felt like some kind of a prisoner. What I hated about it was the dark.

Soon after Garry’s death, I started sleepwalking. It got worse when I moved down, and I would wake up in the area where all the broken tiles were dumped. It’d be pitch black; I’d be terrified and unable to figure out which way to turn to switch on the lights. Everything became frightening, and my dreams would fill with nightmare images of Freddy Krueger waiting for me outside my room.

Most nights, as I listened to the lock turn, I’d fall on my bed and sob into the stuffed Cookie Monster toy I’d had since I was a kid.

Normally I don’t take a mattress with me on a race, but I was worried my leg injury might flare up at some point crossing the Gobi Desert, so I’d packed one specially. I blew it up at the end of the first day and tried to rest up. I had a little iPod with me, but I didn’t bother putting it on. I was fine with just lying back and thinking about the day’s race. I was happy with third place, especially as there was only a minute or two between me, Tommy, and the Romanian, whose name I later found out was Julian.

Instead of an army surplus tent, we were in a yurt that night, and I was looking forward to it being good and warm as the temperature dropped. Meanwhile, though, I guessed I’d have to wait a while before any of my tent mates returned. I ate a little biltong and curled up in my sleeping bag.

It took an hour or so before the first two guys arrived back. I was dozing when I first became aware of them talking, and I heard one of my tent mates, an American named Richard, say, “Whoa! Dion’s back already!” I looked up, smiled, and said hi and congratulated them on finishing the first stage.

Richard went on to say he was planning on speaking with the three Macau guys as soon as they got in. I’d slept all through the first night, but according to Richard, they’d been up late messing with their bags and up early talking incessantly.

I wasn’t worried too much, and thinking about Lucja and how she’d got me into running in the first place, I drifted back to sleep.

I first tried running when we were living in New Zealand. Lucja was managing an eco-hotel, and I was working for a wine exporter. Life was good, and the days of having to hustle the golf courses for food money were behind us. Even better, both our jobs came with plenty of perks, such as free crates of wine and great meals out. Every night we’d put away a couple of bottles of wine, and on weekends we’d eat out. We’d take Curtly, our Saint Bernard (named after legendary West Indian cricketer Curtly Ambrose), out for a walk in the morning, stopping off at a café for sweet potato corn fritters or a full fry-up of eggs, bacon, sausage, beans, mushrooms, tomato, and toast. We might get a pastry on the way home, crack open a bottle of something at lunch, then head out in the evening for a three-course meal with more wine. Later we’d walk Curtly one more