ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

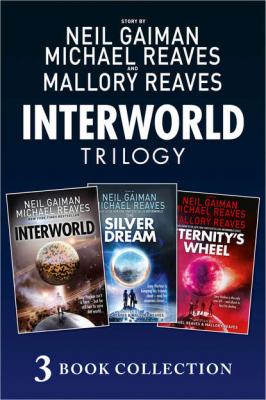

The Complete Interworld Trilogy: Interworld; The Silver Dream; Eternity’s Wheel. Нил Гейман

Читать онлайн.Название The Complete Interworld Trilogy: Interworld; The Silver Dream; Eternity’s Wheel

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780008238063

Автор произведения Нил Гейман

Жанр Детская проза

Издательство HarperCollins

I looked up. The rock that Jo was standing on was crumbling beneath her foot.

“Hey!” I yelled, frantically signaling her to move.

But she ignored me. Then the rock gave way, and Jo slipped back down in a shower of pebbles. She fell directly onto me, knocking both of us down the cliff face.

It was a long way down, and we were tumbling fast together.

I grabbed her by the waist and pushed away from the cliff with my legs. She got the idea at once and flapped hard with her wings. Maybe she couldn’t keep both of us up for long, but we didn’t need to be up for long.

She landed back on the ledge where I’d eaten my soup. “I tried to tell you,” I told her. “Yeah,” she said. “I knew you were trying to get my attention. I just wasn’t going to look at you.”

I stood in the rain and shivered. “How did you know Jay?” I asked her.

“The same way all of us did. One day we started Walking. He came and got us and brought us back here. Mostly he got us out of trouble on the way.”

“Well, that’s how he found me. And he saved my life on the way, three or four times. And he gave up his own life getting me here. But I don’t think he would have treated me like this. And I don’t think he would have let me treat myself like this.”

There was a pause. Then she looked me straight in the eyes, with brown eyes that were like looking into a mirror. “You’re right. I don’t think he would either. I’ll spread the word.”

We climbed back to the top of the cliff in silence then, but it was an okay silence.

After that, things got better. Not much better. And not all the way. But they improved.

AND I’D THOUGHT MR. Dimas’s tests were hard.

Exams on InterWorld would make a Mensa chapter gulp with disbelief. It would have smoke coming out of the ears of our best brain trusts. How do you answer a question like: “Is the improbability factor of a time-reversed world solipsistic or phenomenological?” Or: “Describe six uses for the anti-element pandemonium.” Or how about: “Explicate the gnosis available from Qlippothic Beings of the Seventh Order.”

Try wrestling with stuff like that when you barely passed Home Ec.

I’d been at InterWorld’s boot camp for about twenty weeks now. Twenty weeks of round-the-clock exercises, classes in martial arts I’d never heard of (one of our instructors was from a world where Japan had united with Indochina to produce, among other things, fighting styles that made Tae Kwon Do look like drawing room dancing), survival skills, diplomacy, applied magic, applied science and a host of other things not likely to be found in the curricula of most high schools—or M.I.T., for that matter.

After twenty weeks of InterWorld food and intensive exercise, intensive study—heck, intensive everything—I was as lean as a stick of beef jerky and was working toward the kind of musculature and reflexes I’d seen advertised in the back of old comic books and had always dreamed of sending away for. I also had a head full of facts, customs and other esoterica that would allow me (theoretically) to pass as a native on a good number of the Earths where humanity looked like me.

Of course, my newfound skills at subterfuge and blending in wouldn’t do me much good on some of the other Earths we knew about, such as the one Jakon Haarkanen hailed from. Jakon looked like an example of what might happen if there was a wolf in the family tree maybe thirty thousand years back. She was sleek and feral and weighed about eighty pounds, most of it lean, sinewy muscle covered with short dark fur. She was a real practical joker—she liked to crouch on one of the rafters in the dormitory’s upstairs hall and then surprise you as you walked underneath by dropping down and knocking you to the floor. She had sharp teeth and bright green eyes, and she still looked kind of like me.

As you can maybe tell by the description, Jakon was one of my more distant cousins.

At the moment she and I, along with Josef Hokun and Jerzy Harhkar, were standing on one of the higher balconies of Base Town, taking a rare break from studies and watching a herd of antelope creatures thundering along a narrow river valley beneath us. It was noonish, and the ward fields had been relaxed enough to let the planet’s fresh cooling breezes blow through. I stood next to an Iigiri tree, weighted with clusters of orange-red berries. Before us were flower beds full of royal lilies, honeybush, jove blossoms and blue lotus. There were cycads, conifers and flowers that hadn’t existed on most Earths for millions of years. Their combined scents were enough to make me dizzy, especially after the dry filtered air below levels.

Base Town, like the three or four other domed floating cities across which the forces of InterWorld were spread, had no fixed locale—instead it floated, by a combination of magic and science, across the face of a world where humans were still finding tasty fleas on each other. It was like living in a perpetual tour of a planet-sized national park, vista after vista of spectacular natural beauty. We skimmed the top of forests that spanned half a continent, hung over a waterfall that would never bear the name Niagara, safely sat ringside and watched volcanic eruptions, tornadoes, floods. . . .

There were worse places to go to school.

We were moving east and about due for another phase shift. It happened right on schedule; as we watched, the world before us flickered, then seemed to melt away, flowing into a momentary glimpse of the In-Between’s psychotic landscape before we came back to reality. After the aurora faded we were floating over a barren tundra with the sun high overhead. I could see a herd of aurochs stampeding away and a handful of lugubrious mastodons methodically stripping a large willow tree. The air was colder, and I saw, in the distance, the twinkling cliffs of mountainous glaciers as they crept toward us, shining like icebergs in the sun.

Same valley. Different world.

We do tend to surprise the locals when we enter; that’s why we stick to prehistoric time lines. Less chance of discovery. It was all part of the security measures that InterWorld took to keep the Binary and HEX from finding them. The floating domed cities shifted at random among a cluster of several thousand Earths about halfway down from the Arc’s center. That’s why, even with my skills in Walking the In-Between, I needed help to find the particular world Base Town was on.

The help had come in the form of that strange little equation that Jay had drawn in the bloody sand. Like most of InterWorld’s stuff, it worked by a combination of magic and science.

{IW}:=Ω/∞

wasn’t a mathematical argument, exactly, nor was it entirely a magical spell. It was a paradox equation, like the square root of minus one; a combinatorial abstract, a scientific statement created by magical means.

{IW}:=Ω/∞

was a memetic talisman that each of us carried in our heads and nowhere else, and which allowed us to “home in” through the last few layers of reality to reach Base Town, wherever it was. It was a key, and you needed to be a Walker to work the lock. Flying ships powered by bottled undead Walker energy couldn’t do it; nor could spaceships cruising through the video Static of underspace, powered by deep-frozen 99 percent dead Walkers. You had to be a real live Walker carrying the key in your head for it to work, which made it virtually impossible for either of the empires to find InterWorld.

That was the theory, anyway.

All of which explained the sense of security that allowed us to feel comfortable being out in the open while the four of us quizzed one another for tomorrow’s exams: Basic Theories of Multiphasic Asymmetry in Polarized Reality Planes and The Law of the Indeterminate Trapezoid as Observed in the Ceremony of the Nine Angles.

Even after five months, the majority of the recruits were still pretty