ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

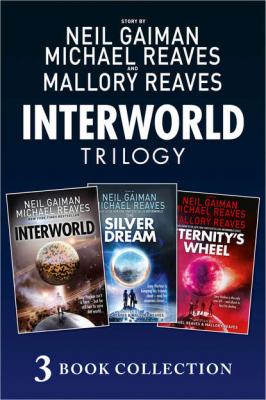

The Complete Interworld Trilogy: Interworld; The Silver Dream; Eternity’s Wheel. Нил Гейман

Читать онлайн.Название The Complete Interworld Trilogy: Interworld; The Silver Dream; Eternity’s Wheel

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780008238063

Автор произведения Нил Гейман

Жанр Детская проза

Издательство HarperCollins

The Binary treat Walkers differently, but no better. They chill us to negative 273º, a hair above absolute zero, hang us from meat hooks, then seal us in these huge hangars on their homeworld, with pipes and wires going into the back of our heads, and keep us there, not quite dead but a long, long way from alive, while they drain our energy and use it to power their interplane travel.

If it’s possible to hate two organizations exactly the same, then that’s how much I hate them.

So Joey did the smart thing—unconsciously, but it was still smart—when the Binary goons showed up. He Walked between worlds again.

I took out the three retiarii without any trouble.

Then I had to find him again. And if I’d thought it hard the first time . . . well, this time he’d charged blindly through the Altiverse, ripping his way through hundreds of probability layers as if they were tissue paper. Like a bull going through a china shop—or a couple of thousand identical china shops.

So I started after him. Again.

It’s strange. I’d forgotten how much I hated these newer Greenvilles. The Greenville I grew up in still had drive-in burger bars with waitresses on roller skates, black-and-white TV and the Green Hornet on the radio. These Greenvilles had mini satellite dishes on the roofs of the houses and people driving cars that looked like giant eggs or like jeeps on steroids. No fins among the lot of them. They had color TVs and video games and home theaters and the Internet. What they didn’t have any more was a town. And they hadn’t even noticed its passing.

I hit a fairly distant Greenville, and finally I felt him like a flare in my mind. I Walked toward him. And saw a HEX ship, all billowing sails and hokey rigging, fading out into the Nowhere-at-All.

I’d lost him. Again. Probably for good this time.

I sat down on the football field and thought hard.

I had two options. One was easy. One was going to be a son of a bitch.

I could go back and tell the Old Man that I’d failed. That HEX had captured a Joseph Harker who had more worldwalking power than any ten Walkers put together. That it wasn’t my fault. And we’d let the matter drop there. Maybe he’d chew me out, maybe he wouldn’t, but I knew that he knew that I’d rake myself over the coals for this one harder and longer than he ever could. Easy.

Or I could try the impossible. It’s a long way back to HEX in one of those galleons. I could try to find Joey Harker and his captors in the Nowhere-at-All. It’s the kind of thing we joke about, back at base. No one’s ever done it. No one ever could.

I couldn’t face telling the Old Man I’d screwed up. It was easier to try the impossible.

So I did.

I Walked into the Nowhere-at-All. And I discovered something none of us knew: Those ships leave a wake. It’s almost a pattern, or a disturbance, in the star fields they fly through. It’s very faint, and only a Walker could sense it.

I had to let the Old Man know about this. This was important. I wondered if the Binary saucers left trails you could follow through the Static.

The only thing we at InterWorld have going for us is this: We can get there long before they can. What takes them hours or days or weeks of travel through the Static or through the Nowhere-at-All, we can do in seconds or minutes, via the In-Between.

I blessed the encounter suit, which minimized the windburn and the cold. Not to mention protected me from the retiarii nets.

I could see the ship in the distance, HEX flags fluttering in the nothingness. I could feel Joey burning like a beacon in my mind. Poor kid. I wondered if he knew what was in store for him if I failed.

I landed on the ship from below and behind, holding on between the rudder and the side of the stern. I waited for a while. They’d have at least a couple of world-class magicians on the ship, and, though the encounter suit would mask me to some extent, it wouldn’t hide the fact that something had changed. I gave them time enough to hunt through the ship and find nothing. Then I went in through a porthole and followed the trail to where they were keeping the kid.

I’m recording this in the In-Between on the way back to base. It’ll make debriefing quicker and easier tomorrow.

Memo to the Old Man: I want both days off when this is done. I deserve them.

WELL, TO BE 100 percent truthful about it, “we” didn’t really jump. Jay jumped, and he was holding onto my windbreaker, so I didn’t really have a lot of choice. My exit was more in the tradition of the Three Stooges than Errol Flynn. I probably would have broken my neck when we landed.

Except we didn’t land.

There was no place to land. We just kept falling. I looked down and could glimpse stars shining through the thin mists below us. A green firecracker explosion happened off to the left of us, buffeting us and knocking us to the right, but it was too far away to do any damage. Above us, the ship swiftly shrank to the size of a bottle cap and then vanished in the darkness above. And Jay and I hurtled into the darkness below.

You know how skydivers rhapsodize about free fall being like flying? I realized then that they had to be lying. It feels like falling. The wind screams past your ears, rushes into your mouth and up your nose, and you have no doubt whatsoever that you’re falling to your death. There’s a reason it’s called “terminal velocity.”

This wasn’t a parachute jump, and we weren’t near Earth or any other planet I could see, but we were definitely falling down, down, down. We must have fallen a good five minutes when Jay finally grabbed my shoulders and wrestled me around so that my ear was next to his mouth. He shouted something, but even with his lips only an inch or so from my ear I couldn’t understand him.

“What?” I screamed back.

He pulled me closer still and shouted, “There’s a portal below us! Walk!”

The first and last time I’d tried to walk on air I was five—I’d strolled blithely off the edge of a six-foot-high cinderblock wall and gotten a broken collarbone for my efforts. They say a cat that walks on a hot stove will never walk on a cold one, and I guess there’s some truth in that—certainly I never again tried to grow wings.

Until now. Now I didn’t really have a choice.

Jay obviously could tell what I was thinking. “Walk, brother, or we’ll fall through the Nowhere-at-All until the wind strips the flesh from our bones! Walk! Not with your legs—with your mind!”

I had no more idea of how to do what he was telling me than a bullfrog knows how to croak the Nutcracker Suite. But he was surely right about one thing—there didn’t seem to be any other way out of our predicament. So I took a deep breath and tried to focus my mind.

It didn’t help that I had no idea what I was trying to focus on. “Walk!” Jay had commanded me. But in order to walk I needed something solid to walk on. So that’s what I concentrated on—my feet treading solid ground.

At first nothing changed. Then I noticed that the screaming wind hitting us from below was lessening. At the same time the mist was thickening. I couldn’t see the stars beneath us anymore. And there was a strange luminescence that seemed to come from the mist that now surrounded us.

We were floating more than falling now. It was like falling in a dream, and it came as no surprise to either of us when we touched down on what seemed to be a cloud.

I suppose Jay had done stranger stuff than this before, and that was why he took it in stride, so to speak. As for me, I had just reached a saturation point, that was all. Considering what I’d been through today, I’d finally come to the conclusion that this was probably all going on between my ears, that I’d somehow fried my brain’s