ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

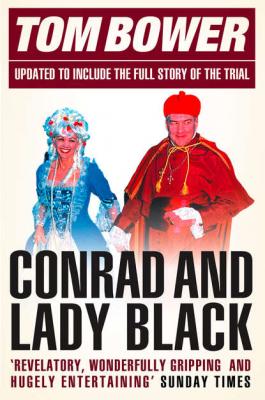

Conrad and Lady Black: Dancing on the Edge. Tom Bower

Читать онлайн.Название Conrad and Lady Black: Dancing on the Edge

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780007388868

Автор произведения Tom Bower

Жанр Биографии и Мемуары

Издательство HarperCollins

The investigation, Black decided, could only be defeated by using the media. Summoning journalists, he explained that he was fighting not for himself but for the poor underdogs who lacked the money to defend themselves against similar ‘injustice’. His refusal to cower and hide, he repeated, was provoking the investigators’ conviction of his guilt. ‘It’s the fascistic mentality of an element of the police,’ he opined. The police, he continued, were behaving like ‘Kafkaesque, Orwellian, Koestlerian thugs’.40 The imagery of ‘Conrad Black – The People’s Champion’ attracted some publicity: and then came the stunt.

In the midst of the investigation Black invited John Fraser, his old school friend, for lunch at Winston’s, Toronto’s best restaurant. As the two men entered, Black saw a slew of the city’s power-brokers – politicians, newspaper publishers and bankers – scattered across the room. ‘Half this restaurant already imagines me wearing a prison suit,’ he growled to Fraser. Sitting with his back to the crowd, he spotted a cockroach above Fraser’s head. ‘Ariana!’ he bellowed, calling the manager. ‘Look at that cockroach! I told you that if you let McMurtry in here I wouldn’t give you my business.’ The whole restaurant burst out laughing.41 Black was a master of theatrics. As the laughter died away, he quietly confessed to Fraser, ‘The whole trauma sometimes stops me getting out of bed.’

The police were unimpressed. Nine criminal charges were drawn up against Black, endorsed by the Attorney General. Until the last moment it seemed that Black would be indicted and tried. He was perilously balanced on the brink. But, literally at the last minute, during a midnight meeting on 9 July 1982, the charges were dropped. The reasons were never explained. Black was ecstatic. ‘I have been absolutely exonerated,’ he exclaimed the following morning, adding, ‘There’s not one shred of evidence of any kind.’ Overnight, he resumed his stance as the master of cool. ‘The jackals and piranhas smelled blood,’ he quipped. ‘They thought they had me, that I was about to go up the chimney in a puff of smoke. [But] I never had any fears how it was going to end up. It’s all atmospherics in the United States. They never believed a goddamn word of all that bunk about racketeering.’42 Behind the reasonableness was real anger towards those who refused to accept his distortions. In particular, he accused Roy McMurtry of being ‘malicious as well as pusillanimous and incompetent’,43 and he damned Linda McQuaig, a Canadian journalist who had revealed details of the police investigation. ‘I thought McQuaig should have been horsewhipped,’ he commented, ‘but I don’t do those things myself and the statutes don’t provide for it.’44 Losing the battle in Cleveland had furnished him with a lesson. ‘For years,’ he later told a Canadian, ‘I wondered what the difference between Canada and the United States really was – apart from the French Canadians and the monarchy. Now I know. This is a gentle place, and that’s a real hardball league down there.’45 As the heat diminished, his self-confidence returned. ‘Tittle tattle,’ he told questioners dismissively. ‘It’s all unimportant.’

Black’s poise was vindicated by Bob Anderson’s agreement in late July 1982 to a settlement. Wiping away the blood, Black thought that he emerged the victor. He paid a further $90 million to become Hanna’s dominant shareholder, bringing the total price to $130 million.* Anderson became a director of Norcen and Black became a director of Hanna. Pertinently, the investment would prove to be disastrous. Hanna did not fulfil Black’s expectations, and the company’s share price tumbled. The Humphreys had the last laugh. By then, Black’s bandwagon had moved on.

Conrad Black emerged having perfected an infallible method for removing the stains on his reputation. As a prolific student of biography, he knew that general impressions were more important than unfavourable details. The trick was to offer reasonable explanations, persuasively interpreting the worst in a more positive light. Over dinner with old friends, he spoke of rewriting his father’s failings, boasted about his theft of the school exam papers as ‘my first true act of capitalism, but no big deal’, and praised Radler’s ruthlessness in sacking newspaper employees. ‘The lobsters don’t get up and walk out of the tank,’ he laughed, enjoying a quip he would use many times thereafter. To propel his self-promotion he had given regular access over the previous years to Peter Newman, the editor of Maclean’s. Every Dr Johnson, thought Black, requires a Boswell. Newman, he recognised, was intelligent but awestruck. The resulting biography, called The Establishment Man, published in October 1982, suited Black’s purpose, not least because it was well written and favourably reviewed. ‘The biggest blow job in Canadian history,’ commented Larry Zolf, a television presenter.

Newman had been encouraged to cast his subject as an intellectual and a philosopher. ‘Every act must have its consequences,’ Black told Newman, posing as the profound historian who did not believe in redemption or atonement.46 ‘Hal Jackman and I agree,’ he continued, ‘that we’re basically more Nietzschean than Hegelian.’ Black ‘revealed’ his sympathy with the ‘exquisitely sad comment by the seventeenth-century French satiric moralist Jean de la Bruyère that “Life is a tragedy for those who feel, and a comedy for those who think.”’47 Newman was encouraged to conclude, ‘He has trouble working out any form of understandable motivation for himself.’ Blessed with that smokescreen, Black’s disarming confession, ‘I may make mistakes, but at the moment I can’t think of any,’ was recorded without comment.48 Despite Newman’s talent, several of Black’s fundamental flaws remained concealed. The cosmetics were impenetrable.

Initially, Black was delighted by the book. Reading his own interpretation of himself fed the conviction that journalists were easily beguiled. Self-interest, however, dictated that he maintain a chasm between himself and potential critics. The publication in Newman’s own Maclean’s of articles describing his Norcen troubles justified that caution. In 1983, fearing further allegations of dishonesty, he issued a writ for defamation against Newman and the magazine. His prosperity depended upon suppressing any objective examination of his fortune-hunting and perpetuating the myth of his being self-made, unblessed by any inheritance: ‘I’m rich and I’m not ashamed of being wealthy. Why should I be? I made all my money fairly.’49

In 1983 Black was, by the scale of his own ambitions, neither rich nor powerful. His gross wealth was about C$200 million, but most of that was used as collateral against loans. His debt was increasing, and he decided that he would sell Argcen’s (Argus’s successor) stake in Standard Broadcasting and Dominion Stores Ltd. Just as he had failed in mining and oil, so he had proved ineffectual at Standard Broadcasting, the owner of several radio stations, and Radler’s attempts to save Dominion had proved dismal. Newspapers, he agreed with Radler, were their best option. By slashing costs they could make profits, and newspaper ownership would satisfy his craving for political influence. His passion was to own the Washington Post, but more realistically he wanted Southam, Canada’s biggest newspaper chain. The owners, Radler spotted, had borrowed large sums to modernise and expand, but the business was deemed to be unprofitable. Only by making massive cuts would the group earn satisfactory profits. Black and Radler bought a small stake in the company, and made an offer wrapped around an