ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

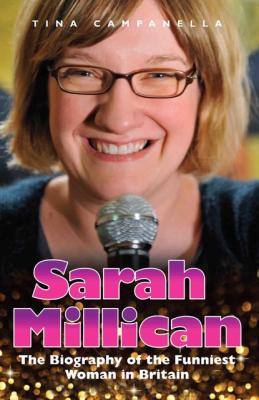

Sarah Millican - The Biography Of The Funniest Woman In Britain. Tina Campanella

Читать онлайн.Название Sarah Millican - The Biography Of The Funniest Woman In Britain

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781782196839

Автор произведения Tina Campanella

Жанр Биографии и Мемуары

Издательство Ingram

‘Anytime you like darling,’ he replied. ‘You’ve always got a home here.’

Safe in the bosom of her family, she fell apart.

Her feelings during that time have been much documented, both as part of her stand-up routines and in countless interviews with national newspapers.

‘We had plans for the rest of our lives and it’s just like somebody has rubbed everything out,’ she told one newspaper. ‘I was 29 and I had thought my marriage was fine,’ she told another. ‘So it was an odd time because I’d never been properly broken-hearted before and for a while I didn’t want to do anything except cry my eyes out all day.’

For a long time, that’s all she did.

Being the ultimate ‘home-girl’, Sarah felt she’d had everything ripped out from underneath her. After all, she’s a woman who still takes a photo from the view of her sofa away on tour with her, and still likes nothing better than to curl up on the sofa, with a blanket across her feet. But now her home was a place of sadness.

‘I bullied him into going to Relate, where I paid £70 for a man to tell us he could do nothing for us. They were the most expensive tissues I’ve ever snotted into,’ she recounted on a Radio 4 show in 2008.

Despite her husband’s devastating admission, the couple had to remain living together until they could sell the flat that they had once planned to make their family home. Now estranged from her husband, Sarah couldn’t bear the thought of going back each night after work. So she turned to a once familiar outlet to occupy her time – writing.

Searching around for something suitable, she enrolled in a new writer programme at her local theatre. ‘I would go there straight after work. It got so the staff knew my name. They kind of saved me in a way.’

Flexing her writing muscles once more, the next few months were a mixture of pain and exhilaration. Some days her life felt utterly broken and she thought she would never recover. On others she felt alive again, and free to do as she pleased. ‘I had what I call my She-Ra moments,’ she has often explained, referencing the popular eighties cartoon figure – a symbol for girl power long before The Spice Girls existed.

‘If somebody said, “Climb that mountain”, I would go, “Well you’ll have to get us the right shoes but I could probably do that.” I’d never felt like that before. I had only ever had the middle ground – and to go from so low to so high was exhilarating.’ She cut her long hair soon afterwards, an act that many people associate with a break-up.

Sarah stored up her painful memories of that time and retreated into the comfort of her family’s arms, as she tried to make sense of what was happening to her life. The house went on the market and eventually sold. Finally the day came when she and her husband had to say their last goodbyes. Packing up the last of her things into a small box, she handed over their cats and shut the door on her once cosy life.

Sarah would have loved to take the pets with her, but her parents were allergic, and it was to their house that she was now headed.

As she walked away, she was understandably reflective. She had lost her husband, home and feline family and was moving back in with her parents, aged nearly 30. She wandered through the park near their home, crying yet more exhausting tears. Then her phone rang and the simple conversation that followed would prove to be the catalyst for a career change that would soon transform her life.

‘Stand-up became my therapy, where I felt valued. The idea of making strangers laugh… it was a euphoric sensation.’

Linda Smith was a waspish and beguiling stand-up comic, who died in 2006 after a three-year battle with ovarian cancer. Voted the Wittiest Living Person by BBC Radio 4 in 2004, Linda’s extremely popular style was based around deadpan diatribes about every day irritations – much like Sarah’s would be.

Her earliest stand-up appearances were benefit concerts in the 1980s, staged in solidarity with the striking British miners. She was a lifelong socialist, with a no-nonsense attitude.

Sarah Millican had never been to a stand-up comedy night, but she did enjoy watching comedians at the theatre. One of those comedians was Linda Smith, and it’s easy to see how the late comic had a huge influence on Sarah’s style.

There are other parallels to be drawn between the two. When Linda died, her fans were shocked. She had kept her illness a secret, because she didn’t want to be thought of as a victim. Instead she carried on performing and appearing on television, overcoming her fear and suffering – and using comedy as a coping mechanism.

Sarah also used comedy as a coping mechanism, and she used the pain of her divorce as a springboard to success. She took her overwhelming sadness and used other people’s laughter to beat it into submission.

The night Sarah and Andrew sold their home, they walked out of the flat in totally different directions, both metaphorically and physically. And bizarrely, on that lonely last walk through the park from her flat, it was Linda Smith who inspired her to begin the long and difficult process of rebuilding her life – though Linda herself would sadly never know.

Linda was performing that night in the Customs House, a popular Newcastle venue, and Sarah, a big fan, had tried to get tickets. Smith was understandably popular in the area, because of her ties to the miners, and sadly all the tickets had sold out. Instead Sarah had been placed on a reserve list.

So when her phone began to ring, and she answered the call through her tears to discover a ticket had become available, Sarah was torn. ‘I thought, “I’m not really in the mood for this but perhaps that’s exactly why I should go,” she has said about that pivotal moment. ‘I can’t do this, I want to sit in the house and eat cake.’

A few hours later, tears were still streaming down her face – but this time they were tears of laughter. ‘I sat on my own and she was wonderful. I came out and my life was just as shit as when I went in, but for an hour and a half I’d forgotten about it.’

It was an inspirational moment. It would be a long time before Sarah would be over the trauma of her divorce, but for that hour and a half Sarah experienced the healing power of a good laugh. ‘Laughing is the most important thing,’ she often says. ‘Laughing can take you out of the life that you have.’

It was the tool she would use to conquer her demons and become that strong feisty woman again – the woman she remembered being, back before her husband broke her heart.

Sarah duly moved back in with her parents, where she would stay for the next two years: ‘I turned to my loving family who supported me and helped me put my life back together.’

Back in her old room she must have felt as if she’d gone backwards in her life instead of forwards. She’d been a ‘grown up’ for years. She’d been married and owned her own flat. Yet now she was sobbing on her old bed like she’d done last as a small child. It can’t have helped when her father gently asked her if she wanted her old Philip Schofield posters out of the loft. Sarah had been a big fan of the presenter when she was a child and had pictures of him all over her wall. ‘No. I’m not 14, I’m divorced,’ she chastised.

Her family cocooned her with love, and her sister in particular was a much-needed source of comfort. She once spent four hours softly stroking Sarah’s hair as she mourned her marriage.

Philip made endless clumsy attempts to console his youngest child. ‘He’s the most big-hearted, kindly person you could meet but sometimes he doesn’t always think through his wording,’ Sarah explained diplomatically to The Shields Gazette in December