ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

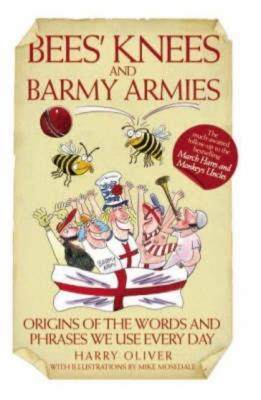

Bees Knees and Barmy Armies - Origins of the Words and Phrases we Use Every Day. Harry Oliver

Читать онлайн.Название Bees Knees and Barmy Armies - Origins of the Words and Phrases we Use Every Day

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781857829440

Автор произведения Harry Oliver

Жанр Энциклопедии

Издательство Ingram

Some sources claim that the phrase derives from a hunter aiming his rifle at his prey, firing and then realising his weapon was half-cocked and that he has done nothing but make a fool of himself. But this explanation doesn’t account for the ‘going off’ part of the expression. More likely is the idea that the guns in the eighteenth century certainly weren’t as reliable as they are today, and often a half-cocked firearm would discharge by accident. This idea not only fits better but more fully explains the potentially terrible repercussions of ‘going off half-cocked’.

Gung Ho

Meaning very eager, zealous or enthusiastic, a ‘gung ho approach’ is something we tend to consider rather bullish and unwise. The adjective derives from the Chinese kung ho, meaning to work together, and during the Second World War it was embraced by United States’ Marines and even became the motto of ‘Carlson’s Raiders,’ the nickname for a guerrilla unit of soldiers serving in the Pacific region under General Evans Carlson. The phrase spread throughout the Marines, and into wider American society with the release in 1943 of the war film Gung Ho!, which told the story of Carlson’s Raiders. It was Carlson’s sometimes irresponsible and careless approach that led to the phrase being used ironically and negatively.

Hit the Ground Running

We use this upbeat phrase to signify a snappy and successful start to an event or enterprise. It’s often said that the phrase originated in either the First or the Second World War. The story goes that, in order to prepare them for the realities of combat, trainee soldiers would be ordered to ‘hit the ground running’ when they were travelling at speed whether on a tank, boat or airplane. This may be true, but the expression existed years before either of the two world wars. By the late 1800s it was used in a literal sense in American civilian life, and the likelihood is that the Army borrowed the phrase because it so aptly describes an essential military manoeuvre. It is easy to see how the phrase came to be useful in today’s fast-paced, competitive world, particularly in the business community.

Knock into a Cocked Hat

If something is ‘knocked into a cocked hat’, it is ruined and rendered worthless. Two possible origins have been suggested, one less convincing than the other. During the American Revolutionary War in the late eighteenth century, ‘cocked hats’ were worn by British and American officers. These hats, three-sided and worn with the rim turned up, were constantly going out of shape, and their uselessness was ridiculed by foot soldiers. So, to knock a fellow soldier into a cocked hat would have been to make him ineffective, to render him pointless. It’s a nice story, yet while it is true that generals wore such silly hats, there is scant evidence that a phrase evolved out of this practice.

Far more plausible is the notion that the expression came from a bowling game which referred to the hats. Three-cornered Hat was a variation of ninepin bowls, in which three-corner pins were set up in a triangle. Each player had three balls per round, and if the three pins remained once the others had been knocked down, the game was all over, or ‘knocked into a cocked hat’.

Stick to Your Guns

To ‘stick to your guns’ is to hold steady in your convictions and not be swayed by the views or actions of others. Perhaps unsurprisingly given the reference to guns, the phrase comes from military life, where the order was commonly issued to a group of soldiers to hold their ground or to an individual to stay at his post. Originally the expression was ‘to stand to your guns’, first recorded in the eighteenth century by Samuel Johnson’s biographer James Boswell, but during the following century ‘stick to your guns’ came to replace it.

Use Your Loaf

This wonderful expression, an encouragement to be smart and use your head, is attached to a rather quaint myth. During the American Civil War soldiers trying to avoid enemy snipers in the forests would jab their bayonets into their daily bread ration and stick the loaf out to make it visible. If the enemy fired at the loaf, the soldiers could rest assured that they had ‘used their loaf’ well – by using a false ‘head’ they had saved their own. A diverting tale, but the truth is that the phrase is good old cockney rhyming slang. ‘Loaf of bread’ equals ‘head’. Say no more.

CHAPTER THREE: ANIMALS AND NATURE

ANIMALS AND NATURE

Bat out of Hell

Meaning to move extremely quickly, this phrase originally came into widespread use in Britain’s Royal Flying Corps during the First World War, when a plane was said to fly ‘like a bat out of hell’. The comparison with bats is easy to understand – they appear to fly very quickly indeed, and give off an air of panic. As for their being ‘out of hell’, you can well imagine they would wish to avoid the burning flames of hell and would fly extra-fast to get away from them. This may only be part of the explanation as to how the phrase came about, though, as it’s likely that the age-old association between bats and the fearsome powers of the occult has something to do with the formulation.

Bats in Your Belfry

If you have ‘bats in your belfry’, you’re a bit crazy. Who coined this twentieth-century phrase is a mystery, but the meaning is simple to unpack. The belfry, or bell tower, is the part of a church where the bells hang, and the tower itself sits on the body of the building. So, metaphorically, your belfry is your head. Bats are well known to hang out in belfries, and equally notorious for flying around erratically, seemingly madly. So, to have bats in your head means you’ve got a whole lot of odd things going on in there.

Bee in Your Bonnet

‘Don’t get a bee in your bonnet!’ is a common adage used in conversation. Meaning ‘Don’t get crazy or worked up’, the phrase is thought to stem from the sixteenth-century saying ‘to have a head full of bees’. The metaphorical notion of a head abuzz with bees equating to craziness must have always been easy to understand, but it was the poet Robert Herrick who threw the bonnet into the mix in his 1648 ‘Mad Maid’s Song’:

Ah! woe is me, woe, woe is me! Alack and well-a-day!

For pity, sir, find out that bee

Which bore my love away.

I’ll seek him in your bonnet brave,

I’ll seek him in your eyes;

Nay, now I think they’ve made his grave

I’ th’ bed of strawberries.

To have a bee flying around the head in the perfect trap formed by a bonnet would be truly maddening. It is assumed that the alliteration of ‘bee’ and ‘bonnet’ meant that Herrick’s take on the phrase stuck.

Bee’s Knees

If something is ‘the bee’s knees’, it is simply smashing, particularly good, perhaps the best. We use the phrase freely, yet the image it conjures up is a strange one. Most of us wouldn’t know what a bee’s knees look like, let alone why we compare wonderful things to a tiny furry body part. One theory is that the phrase puns on the word ‘business’, while another suggests that because bees carry pollen from flower to hive using little