ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

Until Julius Comes. Richard Poplak

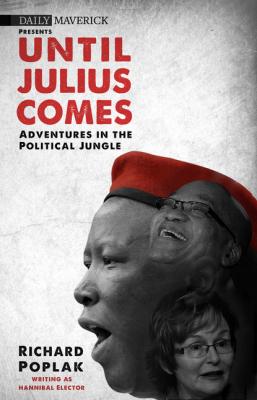

Читать онлайн.Название Until Julius Comes

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780624070108

Автор произведения Richard Poplak

Издательство Ingram

UNTIL

JULIUS

COMES

ADVENTURES IN THE

POLITICAL JUNGLE

RICHARD POPLAK

Tafelberg

History is written as we speak, its borders are mapped long before any of us open our mouths, and written history, which makes the common knowledge out of which our newspapers report the events of the day, creates its own refugees, displaced persons, men and women without a country, cast out of time, the living dead: are you still alive, really?

— Greil Marcus, The Dustbin of History

They searched and investigated and finished but they did not find anything. What I am saying is that this case does not even exist.

— President Jacob Zuma

FOREWORD

‘We beat you,’ said Malusi Gigaba to the media. ‘You campaigned hard against the African National Congress and we defeated you!’

It was Sunday 11 May, and the ANC’s chief campaign strategist was crowing about the outcome of general election 2014, in which his party had scored yet another crushing victory. This was not the result most journalists had anticipated. They had portrayed South Africa as a nation in crisis. They saw a big realignment coming as the ANC foundered under the weight of ten thousand corruption scandals and service-delivery protests, not to mention e-tolls and Nkandla and Marikana. Or schools with no textbooks and hospitals with no medicines.

Considered collectively, these factors were almost certain to slash the ANC’s dominance as voters turned to the opposition for salvation. That’s how journalists saw it. They were wrong. The mighty ANC conceded only three percentage points to its cocky opponents and went home (again!) with 62 per cent of the vote. Elsewhere in the world, this would be termed a landslide. ‘We beat you,’ cried Malusi to the media. And Malusi was dead right.

But did he beat Richard Poplak too?

For those who don’t know him, Mr Poplak is a Joburg boykie whose parents dragged him off to Canada in his teens. Canada was a sensible country where sensible people could build a future without worrying about apartheid and revolution, and all the other shit that kept South Africans awake at night. But it did not really agree with young Poplak, who soon left to pursue a gonzoid dream of blitzing the planet with scorching non-fiction prose-poetry. He wound up in the Islamic world, researching The Sheikh’s Batmobile, a wonderful book about rappers and heavy metal heads trying to live a sex, drugs and rock-’n’-roll fantasy under the eyes of religious police whose intolerance made apartheid Calvinists seem effete. He also wrote a book about growing up in South Africa and another, about Africa, is coming soon to a bookshop near you. Book four is the one you hold in your hand – a collection of stories about South Africa’s 2014 election.

I think it was T.S. Eliot who made up that old saw about how the point of travel is to return at last to the place where you started and see it clearly for the first time. In this respect, Poplak’s sojourns in Toronto, Tehran and Cairo have served to sharpen the bloodshot eye hugely as it gazes upon his old home turf. Poplak is an insider, and yet not. He understands the slang and knows the roads, but notices all manner of things that have become invisible to South Africans, because we’ve blinded ourselves. We do this because we must; because the unfiltered omens, contradictions and anomalies that lie in wait at every turn would otherwise drive us insane. Actually, seeing is almost unbearable. Check it out – by the time the 2014 campaign was done, Poplak’s hold on reason had become tenuous.

But he is laughing, give him that. This is a very funny book, profound at times, and always cutting and clever. But infuriating, too. For instance, I spent election day monitoring a ballot booth on behalf of the Democratic Alliance, a moderate party whose sensible nostrums seem to offer the best way out of our presently grim predicament. I was not pleased to crack these covers and find my leader and my beliefs viciously pilloried, but as I ploughed onwards, there was much to soothe my ire. In this book, everyone gets mauled. Helen Zille is imagined as a Celtic warrior queen, ‘head shaved, face smeared with blood and war paint’, guiding troops into battle. Jessie Duarte is a tired old bullshitter. And, in the aftermath of her traumatic divorce from the DA, Mamphela Ramphele looks ‘shaved to the bone, raw; the only thing keeping her from dissipating into dust is her make-up’.

As his title suggests, Poplak believes that the real winner of the 2014 election was Julius Malema, Commander-in-Chief of the Economic Freedom Fighters and harbinger of what Poplak calls the ‘Age of Idiocy’. It is true that the odds against Juju were almost insuperable and that, under the circumstances, winning 25 seats in Parliament imparts a momentum that might yet propel the fat boy into the state presidency. It could equally be that five years hence, this prediction will look spectacularly stupid. (Not that Poplak actually makes it: he’s too clever for that. But, between the lines, that’s where he thinks we’re going.)

Does it matter?

Forty years have passed since Dr Hunter S. Thompson set forth to cover the 1972 American presidential election, but the resulting book – Fear and Loathing: On the Campaign Trail ’72 – is still in print in the United States, and still taught in journalism schools everywhere. That’s because Fear and Loathing: On the Campaign Trail annihilated the old style of political reportage and replaced it with something infinitely more exciting, albeit not necessarily factual. The drug-crazed Thompson repeatedly described Republican candidate Richard Nixon as a monster riddled with unspeakable perversions, bent on turning America into a fascist state. Thompson was wrong. Does it matter? Not at all. We don’t read Thompson for political analysis. We read him for the manic rush of his prose, for the sharpness of his insights and the savagery of his jokes.

Comparisons are odious, but Mr Poplak has clearly looked at Thompson’s craft and adapted aspects of it for his own devious purposes, which makes Until Julius Comes some sort of far-flung spawn of Fear and Loathing: On the Campaign Trail. Many are called to emulate the Thompson gonzo. Almost all fail. But Until Julius Comes can stand shoulder to shoulder with its illustrious ancestor and not feel in the least ashamed. Odds are therefore that it too will be read and remembered long after the details of who won what in 2014 are forgotten.

If I were Malusi Gigaba, I might just be a bit worried about that.

Rian Malan

GEFÜHLSLEBEN

AN INTRODUCTION

This is a book about madness.

Every word is made up – the words themselves are coined specifically for this undertaking. The incidents detailed herein did not happen; the world in which the essays are set does not exist. There are, of course, moments of clarity to be found within these pages, but they only serve to highlight just how compromised this volume’s version of truth happens to be. A slight correction: this is a work not about, but of madness.

Which is to say it’s a book about South African politics.

Specifically, the book details the 2014 general-election campaign, the fifth such endeavour in South African history. The elections announced the 20-year anniversary of the country’s democratic era, and it’s worth asking – what’s changed since the non-democratic era? Answer: everything. And nothing. South African politics exists in the gulf between those two contradictory positions, exerting its tidal pull on the South African psyche, yanking us from any moorings to sanity we might have had were we not long ago admitted to history’s loony bin.

‘Everything begins in mystery and ends in politics,’ said French essayist Charles Péguy. But imagine a country in which the reverse