ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

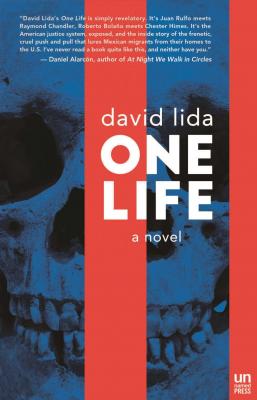

One Life. David Lida

Читать онлайн.Название One Life

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781944700249

Автор произведения David Lida

Жанр Триллеры

Издательство Ingram

It wasn’t as if I never wrote at all. I was perhaps the greatest memo writer in the English language. The lawyers for whom I worked got detailed accounts of every interview I conducted, and longer painstaking ones explaining the life of the family of the accused, the places they were from, and a theory as to what in our client’s life brought him to the moment where he found himself charged with murder. I explained who would make a good witness and why, and which of them would be repellent to a jury of pious, closed-minded trailer trash. I alerted them to the concise menu of what might be a mitigating circumstance: mental illness; great promise thwarted; violence, abuse, and neglect; toxic waste in the well water; previous good deeds heretofore unpunished; a line of people willing to testify that they would be devastated if the client were put to death.

Still, without a writing project of my own, I felt unmoored, unmanned. It was only after I had worked on a few death-penalty cases that I began to feel like I might possibly have a significant story to tell. Every day, matters of life and death were handed to me on a silver platter. If I were to take the project on, whose story would I tell? You could hardly find a better one than that of Roberto, my first case. It happened in Harris County, whose county seat is Houston. It should come as no surprise that about half of my cases came out of Texas, which is not only home to countless Mexicans, but has distinguished itself as the Death-Penalty Capital of the Universe. They could sell T-shirts and coffee mugs with electric chairs on them. At the time I was chosen for Roberto’s case, more people had been sentenced to death in Harris County than any other in the world.

Roberto was undocumented, one of the millions of nameless, faceless Mexicans doing the odd jobs that most people born in the U.S. believe themselves too delicate to negotiate—planting and harvesting, gardening, roofing, maintenance. He was twenty-four, and had distinguished himself with some prior convictions, including a couple of DUIs, possession of a tiny bag of marijuana, and indecency before a minor. (He was busted for that one after consensually French-kissing a fifteen-year-old hillbilly. Her mother, whom he had been screwing, got jealous and pressed charges, which resulted in his deportation back to Zacatecas. Within a few months he had returned to Texas. His rotten luck.)

When Roberto tried to stick up a Dunkin’ Donuts, another customer—an off-duty cop—pulled a gun. Roberto blew his brains out. Sadly, this was not any old cop, but a cop beloved in his community, decorated for bravery, who’d left behind a widow and three sons. We were in such deep water with Roberto that I wanted to ask Donna, the attorney who hired me, why we were even taking the trouble. A Harris County jury would put him in a toaster like a slice of Wonder Bread and turn the dial to burnt.

Donna was extraordinary. If only they were all like her. She ran me ragged all over Zacatecas. Like a bulldog on a short rib, she would not let go of any lead. I got Roberto’s brothers to open up about how their father had been in el gabacho when he was born and constantly taunted him by denying that he was his son. To emphasize the point, he systematically beat the crap out of Roberto. (If anyone deserves the death penalty, it’s usually the father.) I found a beatific nun, a woman whose faith was so palpable that an aura of light surrounded her, like those images of the rays emanating from the Virgin of Guadalupe. She had given Roberto classes in Bible studies when he was seven, and she told the jury she was sure he’d had a calling.

I found a Mexican criminologist who testified about the murders committed by policemen in Zacatecas, and the mistrust nearly everyone in the state felt toward them. I got the hospital records from when he fell off the roof as a seven-year-old and busted his head open. A bunch of his schoolmates testified that he lost consciousness after banging his conk against the goalpost in a soccer match. Goal: Donna found a doctor who swore before the jury that his behavior was consistent with frontal-lobe brain damage.

They gave him life without parole. He will be in jail until he dies, no matter how many years. But the state didn’t kill him. In this business that’s victory.

“When Durex did an international study about sexual satisfaction,” said Mandarino, “Mexican women said they were the most unfulfilled and disappointed on the planet.” Apparently there were other things to talk about besides Walter Benjamin. “They are more miserable than Chinese women who bend over for five minutes in a rice paddy. They are worse off than women in Finland, for whom a fuck only means a respite from seventeen hours of darkness. Eskimo women are blissfully happy compared to ours, and all they do with their men is rub noses. We are so rotten in bed that we even have to call in reserves from other countries. We had to get Richard over there to come and help us out.”

There is no death penalty in Mexico. (In truth, there is no need; in this country people settle their scores with each other on the street in broad daylight.) So my work was only an abstraction to these guys, who saw me first and foremost as a failed writer, someone who published a couple of books that had something to do with Mexico a long time ago, and then dried up. I was their gringo mascot.

Trying to sound casual, Mandarino said, “I think our dear Richard fucked Victoria Díaz last Tuesday.” There had been a party. He didn’t like that she liked me. “I bet you got an incredible blow job, right, Richard?”

“That’s your fantasy,” I said. “We just flirted a little bit.”

Lola arrived and took Mandarino’s right hand in both of hers: the cocaine delivery system, each gram folded inside a tiny piece of paper.

“I’ve been waiting for you forever,” I said, holding up my empty shot glass. “Could you please make it a double this time?”

“Why not, mi amor?” she said, running her fingers through my curly hair. “Anything I have is yours.” As she took the drink orders for the rest of the table, a woman walked into Mi Oficina. Somewhere in her twenties, because of her diminutive stature, she looked about twelve. She had fetching bangs, huge eyes, and wore patterned black tights under a miniskirt. She went straight for Mandarino and gave him a hug.

“This is Olivia, gentlemen,” he said, a proprietary arm around her slender waist. “Where have you been, mi vida?” he asked. “I’ve had to suffer the company of these brutes for hours waiting for you.” And to us: “I gave a workshop at the School for Dynamic Writers and Olivia was by far my most gifted student. One of these days I might even get around to reading something she’s written.”

Lola pulled up a chair for Olivia and set it in between Mandarino and me. She merely nodded when I introduced myself, preferring to engage in obligatory banter with her teacher and the other writers. In Mexico City, there are poor benighted women who like writers. Most have ambitions of writing a book themselves, which if it ever gets published will be one of those books read halfway to the finish line by fifty or a hundred people. Some of them might even read the other half the following year.

Armando from Culiacán asked her what she was working on. “My first book is about to come out,” she said, her eyes alight. “It’s a book of essays about Cinderella.” There is something jarring about a grown woman who looks like a child writing essays about a fairy tale; no doubt Olivia understood this. “I describe the differences between each adaptation: Perrault, the Brothers Grimm, the Disney version.” She was losing him but knew how to reel him back. “And what they all have to do with contemporary sexuality and eroticism.”

“Excellent,” said Armando, having heard only the last three words.

A half hour later, after her conversations with the others ran out of gas, she turned to me and asked, “Are you a writer too?”

I pursed my lips and shook my head.

“Thank God,” she said, having co-opted some of Mandarino’s cynicism. “The last thing the world needs is another one of us. What do you do?”

Most people can describe their work in three words or less. I had to take a deep breath before I let you have it. After, most of the time I had to listen to your position about the death penalty. There were only three: yes, no, and maybe,